Onslow Ford's Queen Victoria Monument.

Onslow Ford's Queen Victoria Monument.

Along with nearby Albert Square, Piccadilly Gardens forms a natural centre to Manchester, being the place to be on a Saturday lunchtime, and a hub for the tram system. There are three important sculptural groups and one additional statue.

Onslow Ford's Queen Victoria Monument.

Onslow Ford's Queen Victoria Monument.

We start with Queen Victoria. This is a grand statue, showing the Queen seated, enveloped in a huge robe which spreads out to the side. Only a tasselled cushion protrudes from among the drapery so we cannot see the seat – but the marble backing rising behind her acts as the high back of her throne. In the middle, providing a frame and almost a halo for her head, is a recess with blue mosaic, and above, the coat of arms and small festoons. Higher still is a broken pediment, with a small bronze figure of St George and the dragon on a plinth as the summit (see this page for more St George and the Dragon statues). To readers of these pages, who may have accompanied the author into a variety of churches, it is tempting to see the marble backing as a conventional monumental tablet, with side pilasters, curvy excrescences flanking those, as so frequently found in 18th and early 19th Century tombstones, entablature with shield above, and the broken pediment of the late baroque.

The sculptor is Onslow Ford, a central figure in the New Sculpture movement, but I am not sure that we would recognise him from the statue of Victoria, though a long look at the drapery, and the ribbon around her neck, would perhaps tell us that a very late 19th Century spirit was being evoked. The St George figure is utterly New Sculpture, and the dragon could have been imagined by Gustave Moreau – but they are small to see from afar, and seen at too much of an angle to appreciate from close by. No, we have to go behind the monument to recognise the sculptor.

Statue of Motherhood on reverse of monument.

Statue of Motherhood on reverse of monument.

Here we have a most evocative statue of Motherhood, standing in a mosaiced niche as at front, but because the figure is smaller, she stands within it. Instead of the arms to the throne, there is a free-standing Corinthian pillar to each side, but apart from that, the setting mirrors the front. The figure of the mother is beautiful, youthful, cradling her two infants, replete and asleep, in her arms. The cloak which forms a cowl over her head serves two purposes – it adds to the sense of protection and nurturing, and in its bulk it provides some aesthetic link to the very different figure of the Queen on the front. Among many works by the prolific and excellent Onslow Ford, he equals but does not surpass this figure.

The Wellington monument (1855/6) must come next, in order of precedence. The bronze statue of the Duke is on a tall plinth, with four allegorical figures seated at the corners, and below, on the base, four relief scenes from the great warrior’s life. The sculptor was Matthew Noble, and this was the statue that made his name. He has other work in Manchester and Salford.

Wellington himself is shown in mature years, standing looking slightly downwards, given a slight stoop, and a profile or near profile emphasising the hooked nose and bushy eyebrows, a thoughtful elder statesman. What a contrast to the younger, full faced figure of the Liverpool Wellington, by G. A. Lawson, or the jaunty one by Marochetti on Woodhouse Moor, Leeds.

In London we have several Wellingtons, most prominently the equestrian one in front of the Royal Exchange by Chantrey, another equestrian one, very straight-backed, by J. E. Boehm by Constitution Arch at the corner of Hyde Park, the youthful, sturdy Guildhall one by John Bell, and perhaps most like the Manchester one, Alfred Stevens’s figure on the monument in St Pauls. There is even another Wellington by Noble, at the Foreign Office, but inside rather than one of the external figures.

Allegorical figures of War, Justice, Peace and Victory.

Allegorical figures of War, Justice, Peace and Victory.

The four allegorical figures are War and Justice at the front, Peace and Victory at the rear. All four have a clean, spare use of detail to give largeness to the design. Unusually, we have three female figures and one male, the latter being War. All are good. War is a mighty Greek warrior, unclad except for his cloak and helment, one hand on the pommel of his sword, the other on the rim of his shield – the only fault being that there is a better such figure by John Bell as part of the Guildhall Wellington group. The Justice figure is an excellent classical design, with Corinthian helmet pulled up Athena-fashion, and with no other accoutrements. Peace, with olive branch and cornucopia, could stand in for Faith given her pose, and for nobility, we have Victory, holding a wreath, and wearing a crown of leaves, a solid necked creature who could have easily fitted on the Warrior women page on this site. (If you like allegorical statues, lots more on these pages.)

The four low relief plaques show two battles - a cavalry charge and an infantry advance; a strategy scene with commanders seated and standing around a cloth-covered table, and some presentation where Nelson stands in front of some panel, with many spectators, perhaps when he is given his command. They are sculpturally interesting for their compositions, which have many figures but enough space to avoid any feeling of clutter, and for the clever posing of what are really very small and sketchy figures.

Sir Robert Peel, by Calder Marshall.

Sir Robert Peel, by Calder Marshall.

The third group is that of Sir Robert Peel, which consists of the figure of the statesman with two allegorical figures. The sculptor was William Calder Marshall, popularised by a series of nudes, widely reproduced in Parian porcelain for the collector, and with a variety of public monuments to his credit, including the Agriculture group on the Albert Memorial in London. The Peel group is described in some detail on this page.

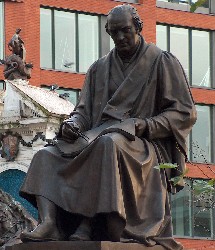

James Watt, by William Theed the Younger.

James Watt, by William Theed the Younger.

Finally, we note the statue of James Watt by William Theed, dating from the mid 1850s. Theed was another contributor to the London Albert Memorial – his work is the Africa group – but he has also has other significant work in Manchester, including Gladstone and others in the Town Hall, the Chetham monument in Manchester Cathedral, and Dalton in Chester Street. Watt is shown seated, with callipers and a sheaf of paper, head somewhat bowed, frowning in deep thought, a bulky figure in a bulky cloak, giving something of a classical impression to a figure in modern clothing. There is considerable nobility to the face.

Manchester sculpture pages - Albert Square // East and south to the Fire station // Adrift group in St Peter's Square

Sculpture in some towns in England // Sculptors

Visits to this page from 13 Mar 2014: 3,149 since 6 October 2024