Classical and Gothic - steeples of St Philip's and St John's, Salford.

Classical and Gothic - steeples of St Philip's and St John's, Salford.

Classical and Gothic - steeples of St Philip's and St John's, Salford.

Classical and Gothic - steeples of St Philip's and St John's, Salford.

Salford has a small number of good statues and architectural sculpture in terra cotta, two major churches, and a Museum and Art Gallery, which all lie along Chapel Street. Salford is a short walk from central Manchester. The two natural ways to go there, if travelling from Manchester, are to start from the Cathedral and walk along Chapel Street from the very beginning, or to go from Deansgate along Quay Street, up New Quay Street over the Irwell, which then briefly becomes Irwell Street and Trinity Way, and then left into Chapel Street when it has already become a major road.

Salford Cinema, and detail of terra cotta; Salford Town Hall, by Richard Lane.

Either way, our first interesting building is on the corner of Trinity Way with Chapel Street. It is on the right hand (northern) side, as are most of the buildings we want to see. This is the former Salford Cinema, with a good frontage of terra cotta, featuring garlands of fruit, stylised leafy fronds bordering the round windows, and other somewhat art nouveau decoration. There is a nice cupola on the corner above the principal entrance. Dated 1912.

Next is a small open space with a few trees. Behind these is Salford Town Hall, a classical edifice with a large portico giving an apparent massiveness to the building larger than its actual size – two central Doric pillars, square pilasters to left and right, and at the corners; empty portico above, with wreaths below it, above each pillar or pilaster. This is one the principal works of Richard Lane, a significant early Manchester architect, and this was early in his career, being designed in 1825.

Education Office, and terra cotta detailing.

Education Office, and terra cotta detailing.

Next, a few doors down, is the splendid Salford Education Office, originally the Salford School Board Offices, dated 1895, entirely clad in pale terra cotta tile, bar the semi-basement level in granite; three principal floors, then a balustrade above which are three short towers, with set back chimneys and little roofed towers, which at a distance along the road give a fine and varied skyline. There is a central main door, only slightly emphasised by attached columns at each level, Doric and Ionic, a balcony , a decorative frieze, and the central turret. A second door is to our right as we face the building, again with slightly projecting features, and is balanced at the lefternmost end with a shallow bay window at first and second floors. There is good small detail, giving some variety from a distance, and for the pedestrian passing or entering the building, a human scale to what is otherwise a very large building. Among the ornament note especially the female faces on the door pillars, and the coat of arms, with the motto ‘Integrity and Industry’, two rampant horses, rather leonine in build, and grotesqued dolphins below. Apparently W.J. Neatby was the designer - those female faces make this almost certain - working for Doulton's of Lambeth.

Opposite it, the Old Nelson Pub, a crumbling Edwardian building with a cupola which should be preserved. Just along from this, the Old Bank Theatre, also much abused, but under the peeling paint a rather good art deco building with a sympol of a bird holding a small branch, gull-like in the face, eagle-like in the talons, and at the top, a repeating Egyptianised frieze - see bottom of page.

St John Roman Catholic Cathedral, and the two saints.

St John Roman Catholic Cathedral, and the two saints.

Back on the right hand side of the road is the Roman Catholic Cathedral of St John, a dominating building, designed in 1845 by M.E. Hadfield and W.G. Weightman, a partnership of Manchester Gothic architects. The building shows to advantage from all aspects, the front to Chapel street showing the tall nave and two aisles, with a clustering of steeples and buttresses; from an angle the cruciform structure of the church is apparent; and from the side or further off, the height of the spire is most impressive. On the Chapel Street front we have three statues. Two of these are saints, on the main buttresses to left and right of the entrance, one with long sword held point down, who would be St John, and to the right, St Peter with book and keys. Good Gothic drapery somewhat in the manner of the 17th Century, but the orangey stone, so suitable for the main cladding of the building, is rather soft for the sculpture, and the figure of St James is rather crumbled in the face. Above and central is a seated Virgin and Child, which despite being set back in a niche, is also in a poor state of preservation.

St Philip's Chapel, by Smirke.

St Philip's Chapel, by Smirke.

Just beyond the Cathedral is the unappetising crossroads with Islington Way, and already we can see the tower of our second important religious building, which is St Philips Chapel. It is set well back from Chapel Street, and presents a perfect classical façade, with semi-circular porch with Ionic pillars all round, and a clock tower behind, rising in two storeys via attached pillars and flat pilasters to a cupola. The architect was Sir Robert Smirke, the designer of the British Museum, and of his various churches, this is surely the best. On seeing it for the first time, ignorant of its provenance, I thought first of John Soane – who Smirke briefly worked for. The building is of 1822, so the earliest of the buildings on our walk, and was replicated in London at St Mary Wyndham Place, near to Marylebone Station.

Boer War Memorial to Lancashire Fusiliers, by Frampton.

Boer War Memorial to Lancashire Fusiliers, by Frampton.

Continuing, on the right is the vast Salford Royal Hospital, facing Oldfield Road, and here on the left is an important statue – the Boer War Memorial to the Lancashire Fusiliers, a lively work showing a soldier standing, holding his heavy hat aloft in one hand in a triumphant wave, his other hand on his upturned, bayoneted rifle. Another hat-raising War Memorial is Joseph Whitehead’s one in Worthing, and the other hat-raiser who leaps to mind is Charles Bacon’s Albert at Holborn Circus in London. Regardless, our one here in Salford is a superior work, most especially in the dynamism of the pose, embodying a restless energetic figure, alive with the excitement of victory. The sculptor was George Frampton, an important and versatile artist of what became known as the New Sculpture movement, among whose many public works is another version of this statue, at Bury.

We carry on along Chapel Street. On the left hand side, another boarded up building, the Black Horse Hotel, with a set of four keystones of particular merit. First an unusual one showing crossed blacksmith’s hammers, and a variety of other tools of that trade, including horseshoes; the next shows a head of the black horse itself, with flowing mane; the other two are the cruel visages of some forest deity with grapes as a crown, and a satyr with horns and a many-stranded beard. (For a general page on keystones, see this page.)

Proceeding a few minutes past terraced houses on the left, and the curve of the river on the right, we come to Salford University, where is the Salford Museum and Art Gallery, set back behind a green space. Thus far, this site has kept out of the galleries, but we may mention the several interesting statues inside which should certainly be seen by the visitor:

The sculptures sit in a gallery of Victorian art, which includes some important oil paintings, including a personal favorite, J. C. Dollman’s work Famine.

The exterior of the gallery has on its left hand side a series of seven keystone heads, which seem to be generally representative of the Continents and Civilisation. We have a bearded man with castellated crown, who would do for Europe, a second bearded man with Christlike countenance and a turban, who might be Arabia, an obscure feminine face with leafy branches in her wavy hair and crossed arrows below, an androgynous, presumably male youth with Hoplite helmet pulled up Athena-fashion, and a necklace of twisted snakes, a second, plumper female face with leaves in her hair, and a crossed bugle and pipes across her neck, a grim African woman with heavy necklace, earrings and short feathered headdress, and finally a stern North American warrior with longer feathers, and a necklace of bear’s claws. All in a red sandstone, highly accomplished work, but as generally the case with keystones, anonymous.

Matthew Noble's Queen Victoria and Albert.

Matthew Noble's Queen Victoria and Albert.

Outside on the green space in front of the Museum are two statues, of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, among the trees. The work of Matthew Noble, but executed at different times, they are in Portland stone, and stand on tall plinths. Victoria is much damaged by time, her face crumbled and hand missing. However, we still see a youthful, elegantly robed figure, wearing a circlet and her other hand, I think, on a full crown resting on a pedestal.

Albert has lasted far better, and is instantly recognisable. He is more lightly robed, and carries in one hand a mortar board, in the other, some scroll, and behind him is a heap of books on which rests a globe. It is Matthew Noble who is responsible for Manchester’s Albert Memorial (shown on the main Manchester Albert Square page), the Wellington Monument in Piccadilly Gardens, and he also has busts of Cromwell and Thomas Goadsby in the Town Hall.

Spandrel girls and panels on the Peel building, principal frontage.

The Western side of the green space is occupied by a University building, the Peel building, which has good architectural sculpture. It is a bright red terra cotta effort dating from the later 1890s. Three stories high, with the central portion projecting and rising a further storey to a gable. The sculptural adornment consists of figural sculpture as follows:

The whole ensemble is extremely competently done, with good faces to the figures, extremely good drapery – see for example the left spandrel figure and the sculptor at the top, and the character of the chemists.

Side of Peel Building to Chapel Street, and the two processional panels.

Side of Peel Building to Chapel Street, and the two processional panels.

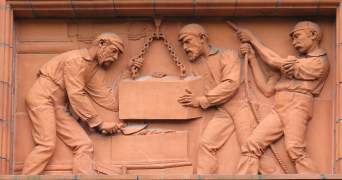

Around the corner, on the side facing the road, are two further groups flanking one of the windows. Each consists of four girls, standing in procession. They are draped Greek style, their hair likewise. Two on the left carry bobbins, those to the right hold wound up cloth, a hank of thread, and have a loom, thus referring to one of the main industries of Victorian Manchester. Again, very fine work in the sombre faces, well observed hands, and enrobed figures. But who was the sculptor?

That is as far as we go along Chapel Street. We return on the other side of the road. Before leaving the area, we note that more or less opposite the Museum and Art Gallery stands a cenotaph in Portland Stone, recording WW1 and WW2 campaigns on front and sides, and with a sphinx on top, the single word Egypt on each side of its base. Other minor decoration includes wreaths and flowers. (For more statues of sphinxes, see this page.)

Along the way, left hand side of Chapel St - Old Nelson Pub, Old Bank Theatre, Black Horse Hotel keystone, and Cenotaph.

Manchester sculpture pages - Albert Square

Sculpture in some towns in England // Sculptors

Visits to this page from 16 Sept 2012: 1,843 since 10 September 2024