In the centre of Victorian Manchester is Albert Square, dominated by Waterhouse s Town Hall. The square itself contains civic statues, and importantly, Manchester s Albert Memorial, and around the square are interesting buildings with sculptural details - an introducition to the remarkable variety and inventiveness of the decorations on Manchester buildings.

We start with the Albert Memorial, shown above - I wanted to show this picture because of the nice colours, and can only apologise for a touch of the old inner ear problem which led to me not holding the camera straight. To the visitor from London, the shrinelike shape feels instantly familiar, as a miniature version of the national Albert Memorial in Hyde Park. It comes as something of a shock, therefore, to find out that this one came first. The Gothic design was by the Manchester architect Thomas Worthington, who was one of the most significant contributors to the Victorian Manchester cityscape. It was erected from 1862-67, and in an eerie similarity to the London Albert Memorial, it too had a difficult escape from quite serious proposals by the Barbarians to demolish it.

Matthew Noble's figure of Prince Albert.

Matthew Noble's figure of Prince Albert.

The central standing figure of Albert is by the sculptor Matthew Noble, and shows him standing, one foot forward and hand on hip as if pausing to look at something before striding forward. He wears ceremonial dress and a chain of office, and a long cloak which adds structural support. He is poised underneath a tall canopy, held up by four solid square pillars, with clusters of narrow columns towards the interior like a Gothic cathedral. Little spikes all the way up the arches give a dramatic silhouette to the monument in the evening. The monument rises in spiky verticality via steep roofs and gables to the central spire, and at each corner rises a tall pinnacle, making the whole remarkably like a church tower. These pinnacles each bear three little statues round the base, and one interior one at the higher level. They are small and made in stone, and some have not lasted particularly well. The upper angelic figures represent the Arts, Sciences, Agriculture and Commerce, and the lower ones are subsidiary or related allegories to these: thus Painting, Sculpture, Architecture and Music under Art, the Continents under Commerce, four Scientific disciplines, and the four Seasons. The effects of time and pollution on the soft pale stone, and the small size of the figures, make some of them fairly unrecognisable, but others remain clear. Further little angels with trumpets etc are at the tops of the gables, and there are various small gargoyles and climbing dragons, and little heads in circles, to add to the medieval feel. On the outer sides of the pillars are various shields, and more at the bases, and along the sides of the pedestal are panels with further symbolic objects, though the symbolism is less clear in some cases than it may have been a century and a half ago.

As a whole, the sculptural decoration feels like architectural sculpture, whereas in London, the statues are clearly works of art in their own right which are in the setting of the memorial. While the Manchester memorial is beautiful in its own way, and an asset, there must be concern as to whether it will last another 50 or 100 years without much of the sculpture and other details wearing away entirely.

There are four commemorative statues in the square:

Woolner's Bishop of Manchester, and panels underneath.

Woolner's Bishop of Manchester, and panels underneath.

James Fraser, Bishop of Manchester, erected 1887, by Thomas Woolner. He stands on a granite plinth, facing outwards from the square. A very calm statue, with a subtle and sympathetic rendering of the face. In summer, the statue tends to suffer somewhat through being obscured by the overhanging tree. Around the plinth are three bronze panels in relief, finely rendered scenes showing the Bishop with the congregation, attending the sick, and at a meeting of industrial workers. As ever with Woolner, the composition is careful and there are charming details, such as a woman handing a daffodil to a patient in his sick bed. There is a monument with effigy to Bishop Fraser in Manchester Cathedral.

Bruce-Joy's statues of John Bright and Oliver Heywood.

Bruce-Joy's statues of John Bright and Oliver Heywood.

John Bright is one of two stone statues by Albert Bruce-Joy, and dates from 1892. Despite the standing position, a sense of movement is conveyed by the pose through a slight tilt to hips and shoulders.

Oliver Heywood is Bruce-Joy s second statue, and by contrast is shown leaning on a short square pillar, head downward-turned as if in tiredness rather than addressing people below his elevated position.

Finally, the statue of Gladstone is by Mario Raggi, another bronze. The instantly recognisable figure is shown declaiming, one hand raised and pointing to emphasise his point, the other clutching a scroll, we can imagine a speech which he knows well and passionately and has no need to refer to. While all four statues are in rather similar clothing, with a knee-length outer coat and, for three of them, buttoned waistcoat underneath, Raggi s treatment of the drapery is a contrast to the others, with a complex surface of the fabric, which is folded and stretched and twisted over the figure; a characteristic of the sculptor.

Alfred Waterhouse s Town Hall is of enough sculptural interest to have a separate page. On this page we look at the buildings to the flanking sides of Albert Square.

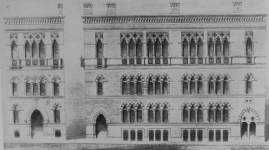

Elevation of Thomas Worthington's Memorial Hall, Albert Buildings and Memorial Hall, Head of Albert.

As we face the Town Hall, there are a range of other interesting buildings, with sculptured decoration to our right (South side of Square), and going round into Mount Street. We start furthest from the Town Hall, at the corner with Southmill Street, with Lloyd Street behind us. The corner building is the Memorial Hall, dating from 1864-1866, with nicely sculpted text above the ground floor that it was erected in commemoration of the year 1662. The architect was Thomas Worthington, whose work we met as designer of the Albert Memorial in the Square. What we see is a building of many Gothic windows, rather Venetian, rather Ruskinian, rather polychromatic with its pale stone, coloured with black and red bands around the window tops, and with alternate banding of red brick and stone all the way up. The upper floor is double height, and the main frontage is to Southmill Street round the corner.

Next is a less flamboyant, sandstone building, 16 Albert Square, formerly Albert Chambers and now a Noodle bar. Italianate, by Clegg and Knowles, dating apparently from 1873. As befits the original name, a little head of Prince Albert glares out from above the door, accompanied among the foliage by a lion, and, less obviously, a goat. There are bands of other small floralities higher up, forming an accent rather than more.

Bridgewater House, 17-18 Albert Square - Gladstone, Cromwell, and who else?.

Next, no. 17-18 bears the date 1873 and is by the same architects, in the same pale sandstone, again Italianate and a shade more Gothic, and a bit more showy. It was once the office of the Bridgewater Canal company, and is now called Carlton House. It is more decorated, and matches well to the spirit of Waterhouse s Town Hall. There are a variety of sculpted pillar tops, brackets, little flower roundels and bands of foliage, and four heads in panels of leafy design above the second floor level. They are all portraits, but of who? One is almost certainly Gladstone, a second, with long hair, is likely Cromwell, but who are the Francis Drakelike explorer in a brimmed hat and the fourth one with a craggy face?

Figural sculpture on no. 21, and 2 Mount Street: Scottish Widows fund, St Andrew, Victoria.

The corner building is St Andrew s Chambers, no. 21 Albert Square, flatter, but again Gothic in a Waterhouseish way, and with charming little turrets to the sky. There are just two bays to the square, one more as a truncated corner, and the main part of the building is along Mount Street. It was built by G. T. Redmayne in 1874 for Scottish Widows, the life assurance society, and towards the Square, above the main door is a roundel with high relief sculpture of a robed female figure distributing a large coin from her box marked Fund to a kneeling elderly woman. To the other side stands a boy, already with a pouch of cash to save with the Society. Good work, the sculptor unfortunately anonymous. Around the corner in Mount Street at second storey level is a niche with a full size stone statue of St Andrew. He is shown as an elderly man with flowing slightly forked beard, holding his cross of course, and with his Biblical cloak nicely wrapped around him; again a work of some character.

Heraldic beasts on the Lawrence Buildingss.

Heraldic beasts on the Lawrence Buildingss.

We cannot resist a few more steps down the beginning of Mount Street. The next building, a across a little alley called County Street, continues with the same stone and theme, and is no. 2 Mount Street, called Lawrence Buildings over the spiky door, and is again Gothic with little pinnacles, and more decoration. Again we have a full figure high up in a niche, a crowned queen with orb and sceptre, a slightly unconventional rendering of a young Queen Victoria with plaited hair. The corner to Central Street, which projects as something of an attached turret, is also highly decorated, with the door flanked by splendid heraldic beasts, for the Inland Revenue (a wise use of our taxes): lion and unicorn, and higher up are shields of arms, flowers, little heads, projecting dragon gargoyles, and best of all, at the top, four freestanding little heraldic dragons, each on its own pedestal. Excellent! (For more unicorns , see this page; and for dragons, see this page.) Again from about 1874, this time by the architects Pennington and Bridgen.

We go a few steps further across the street (Central Street) to see a dignified classical building, Friends Meeting House, thus Quaker, with ionic Portico with four attached columns. This is the work of the significant Manchester architect Richard Lane, and dates from 1828-30. We turn back to Albert Square.

Fierce beasts from the north side of the Square, and heads in Bow Lane.

This side of the Square is less distinguished, containing two buildings with minor sculptural decoration. On the corner of Cross Street is a Tudorish sandstone and red brick building which goes round the corner, with little stone decorations above the first floor below the red brick, at the string course as it were. Pennington and Brigden again, a couple of years later than the other side of the Square.

The second building, back to pale sandstone, is the bulkier Northern Assurance Buildings. The edifice is dated 1902 and is apparently by Waddington, Son and Dunkerley. It is embellished with snarling lions heads biting on globes, and lots of baroque detail at the top, with shell designs, vaguely floral, and a top central lion rampant with crown above. A dome marks the corner, and the building goes round into Clarence Street. Following this, across Bow Lane, the next building has a narrow corner bearing three little heads in helmets, perhaps firemen. We end with a last, straighter, picture of the Albert Memorial.

Worthington's Albert Memorial with Noble's statue, and Oliver Heywood.

Worthington's Albert Memorial with Noble's statue, and Oliver Heywood.

Town Hall // Piccadilly Gardens // Free Trade Hall // Coroner's Court and Fire Station sculpture

Abraham Lincoln Statue, Lincoln Square // Bridge Street keystones // Manchester Cathedral

Adrift group in St Peter's Square

North and west to Salford // Sculpture in Oldham

Sculpture in some towns in England // Sculptors

Visits to this page from 13 Mar 2014: 2,454 since 9 September 2024