L is for Love, and allegorical statues depicting Love are frequent, particularly towards the turn of the 19th Century. Putting together this note, the first statue that came to mind was French - Rodin’s The Kiss, as exemplifying emotional love between man and woman, and then a moment’s thought led to the idea that of course in Victorian and Edwardian Britain, this was not the sort of allegorical Love we find at all. Maternal Love comes to mind as a sculptured group; and the statue of Eros with his bow, as emblematic of falling in Love. But hardly physical love between man and woman. We do have several different manifestations of Victorian and Edwardian sculptures of Love, though and Eros on the one hand and Maternal Love on the other give our two families: those single figures, of one or another kind of abstract Love, as with Eros; and pairs or groups of figures, where they love each other as in Maternal Love, or Love is interacting with some other, for example Love and Life.

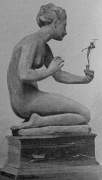

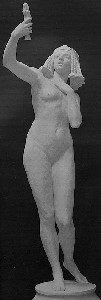

Starting with the single figures, then. If not Eros, Love as a single figure is inevitably a female figure. She may be clothed or semi-draped or nude, as in the figure by Giovanni Fontana, the Prisoner of Love, at the top of this page. A rather charming Pre-Raphaelite Love, evoking a similar spirit, standing with arms upraised almost in the form of a Caryatid, was sculpted by Thomas Woolner. Our figure of Love is always young and beautiful, and often shy, to show her chasteness, as in the charming figure Love the Conqueror, below left, by F. W. Pomeroy – a version of this one is at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. An unusually bold sculpture is Soft Eyes Looked Love, by A. C. Lucchesi, below right.

Love the Conqueror, and Soft Eyes Looked Love.

Love the Conqueror, and Soft Eyes Looked Love.

These last two were from the New Sculpture movement, and the subject was naturally attractive to them. Here is a work by another of the band, H. C. Fehr, an Egyptianized version, subtly posed, which is An Invocation to the Goddess of Love. And simply because it is a favourite of mine, and to help complete a collection of New Sculptors, below right is Reynolds-Stephens’ Youth – happy in Beauty, Life and Love and Everything.

Invocation to the Goddess of Love.

Youth – happy in Beauty, Life and Love and Everything.

Youth – happy in Beauty, Life and Love and Everything.

Figures of Eros are epitomised by the iconic Piccadilly Circus statue by Alfred Gilbert, another of the New Sculptors, indeed, the leader of the movement. Eros is a young boy, winged, pure of face. He is generally without clothing, or at most a few light drapes, and may range in age from an infant amorini to a tall youth of ten or so. His wings are generally small and goose-like, though longer angel-like wings are not unknown, and he nearly invariably holds bow and arrows. See this page for lots of pictures of the Eros.

So much for the single figure. For pairs or groups, we start with Maternal Love – a feminine figure with one or more infants, as in this figure.

In this case, our feminine figure is typically draped, and joyful with her offspring, cradling or playing with the child. Thus we may draw some distinction between sculptural groups of Maternal Love and Maternity, where the latter is generally more serious, emblematic of the act of motherhood rather than the love which springs from it. Maternal Love more usually has a single infant child –an undivided love – whereas Maternity will normally have two or three. Figures of Maternal Love are always youthful, in my experience; Maternity may be more mature, as may the children, while Maternal Love almost always has a young infant. A counter-example, rather unusual in several aspects, and cloyingly sentimental, is the one below left, depicting A Mother’s Love. As an antidote to that, below right is an equally atypical and rather grim Mother’s Love, a saintly soon-to-be crucified Christian martyr, feeding her infant with almost her dying breath.

On to loving couples. They are generally nude. The Crown of Love by W.R. Colton, below left, is typical: two nude figures, she embracing his head and hair; or this family group, below right, also with an embrace. Rather akin is a group of the Triumph of Love, by Patrick Macdowell, with an infant held high by a rather saintly but triumphant couple.

Such holding is not uncommon, but this is a clutching hold of, possessive embrace, rather than anything passionate, as our Rodin example. Generally to find such in England we have to go to the 20th Century for Love as amour, as in this one, Young Lovers, by Georg Erlich, by St Paul’s Cathedral – and even this is an import rather than by a British sculptor. From that time, we do have of course Epstein, and his is a physical, rather primaeval Love. A rare exception from Edwardian times is this panel of Life and Love, Sacred and Profane, by Derwent Wood. The profane couple to the left shows the man with arrogant and heedless stride, with his woman posed in somewhat brazen fashion, exchanging a laviscious kiss. By contrast on the right is Sacred Love, a dignified couple with their infant, symbol of their love, with an angel casting a protective wing over them.

Georg Erlich's Young Lovers, and Sacred and Profane Love.

Then we have a whole group with Love as an abstract, with some other allegorical figure. Love may be an Eros figure, as in Love and the Vestal by S. Nicholson Babb, and Love the Laggard, a work from well into the 20th Century by H. A. Pegram. Far earlier, we may mention in passing a rare grown-up Love as an Apollo figure in a panel of the Marriage of Psyche and Celestial Love, by John Gibson, which is at the Royal Academy; and the First Whisperer of Love by William Calder Marshall, as typical of the older school.

Love and the Vestal, and Love and the Laggard.

Onward again to the turn of the century are two works by C. J. Allen: a charming group called A Dream of Love, with a winged, male figure protectively over a drowsing nude girl, and holding a small Eros figure; and another Eros in Love and the Mermaid, a group of innocent first love, which has to be contrasted with that other mermaid group, Henry Pegram's Hylas (see this page; and see this page if you want other mermaid statues).

C. J Allen's allegorical figures of Love etc.

C. J Allen's allegorical figures of Love etc.

We end with two contrasting pieces. Below left, we have a genuinely passionate embrace between two allegorical figures, in Love and Soul by Crossland McClure, with the pose of the nude figure, the swirling inwardly-binding composition, and the nervous tenseness of the muscles of body and limbs all attesting to a physicality lacking in almost all our other examples. And below right, from half a century earlier, is the rather over the top example of mid-19th Century sentimentality, not British at all but approvingly noted here in the art magazines of the time, A Basket of Love by Thorwaldsen. Cloyingly sweet, but irresistible.

Love and the Soul, and A Basket of Love.

Back to Allegorical sculpture - K // Onward to Allegorical sculpture - M // Full Alphabet of Allegorical sculpture

Sculpture in England // Sculptors

Visits to this page from 12 Feb 2012: 11,256