St Mary Wanstead, London/Essex - Monuments

St Mary Wanstead, in that part of East London once part of Essex, contains the outstanding, enormous monument to Josiah Child, attributed to the sculptor John Nost. There are a variety of panel monuments, completely dwarfed in comparison, but of interest in their own right, including signed works by Peter Scheemakers in the mid-18th Century, and by Chantrey, Westmacott, and John Bacon Junior in the early 19th Century.

The Church building

A few words on the Church itself, before going in to look at the monuments. St Mary Virgin, Wanstead is box-shaped, basilica style building of brick faced with Portland stone, with two rows of round-topped windows to the sides, a Doric portico at the front, empty pediment above and behind that, and a small Classical bell-tower with a cupola on top, a sloping roof behind. The Church was erected in 1787-90, Thomas Hardwick being the architect, and, so Gunnis the monumental historian tells us, the masons were William Miller and George Boucock, who also built St Martin Ludgate in the City of London. The previous medieval church of Wanstead had been considered too small and was demolished – it might have been retained, as it stood a little to one side of the current Church.

Wanstead St Mary, Interior views.

Inside, the Church feels tall, open and light: the aisles are full height, separated from the nave by thin columns, and full length galleries. The entrance is under the massive organ, and at the other end, through the generous chancel arch is the dominatingly large and impressive monument to Josiah Child. The other monuments, a range of panels, are dotted along the aisles and with a few in the galleries.

We start of course with the enormous Child monument, and then take the rest in date order.

Josiah [Josias] Child, d.1699

Baronet Joshua Child monument, attributed to the sculptor John Nost II.

‘...a most splendid Monument for Sir Josiah Child Bar[onet], where his Effigies, cut out in white Marble at Length stands; Pointing with one his Fingers downward, directing to the Inscription underneath, to shew who he was; his three Wives, whose Daughters they were, and to whom married, namely their former Husbands; what Children by each. The Monument mentioned to be set up by Sir Richard Child, Bar[onet] his Son surviving, now Earl Tilney.

Underneath lyeth along, on his Side, his Son Bernard, who was elder Brother to Richard.

... There are divers curiously engraven Marble Figures on each Side of the Monument, besides that of his Son Bernard underneath, viz. Two Women fitting on either Side, in very melancholic, lamenting Postures: One leaning her head upon her Hand, the other Hand stretched downward; the other Woman closing her Hands together, and wringing them: Both with Veils over their Heads. And there are likewise, by Way of Ornament, Boys in mourning Postures, and one of them blowing up a Bubble. ...’

The composition centres on Josiah Child (pictured above), standing under a triumphal arch, on a tiered base accommodating a pair of cherubs, and as Stype noted, the reclining figure of his son Bernard Child; the inscription is on the lowest tier. Other figure sculpture includes Strype’s melancholic women, and on the very top, two trumpeting angels. The statue of Josiah Child is in the classic style of the 18th Century – strutting forward with one foot extended, hand on hip, the other in a studied gesture, head proud and looking outward rather than downward to the spectator. Again characteristically, and oddly to our eyes, the figure combines the full wig of his times with Classical garb – cuirass (body armour), Roman toga and sandals and a great sweep of cloak and twisted drapery about the waist; his physique too is a mix of the 17th Century merchant, a little rounded in the protruding stomach, and with a middle-aged bureaucrat’s face, combined with the muscular arms and legs of a Roman soldier. Pretentious perhaps, but gloriously so.

If Josiah Child is the noble Roman in action, his son represents the noble relaxing, reclining on a tasselled cushion, his free hand open expansively as if conversing. Again, he wears a cuirass, and is bewigged and sandalled, but has a long drape over his legs. Like his father too, he is prideful, head tilted somewhat back. The quality of both figures is superb: look especially at the expressive hands, and the profile and neck of Bernard Child. There is a largeness to the drapery, with broad masses appropriate to the scale of the monument.

The two mourning female figures seated to either side are excellent things too: hooded, appearing like some medieval queens; one has her hands clasped in prayer, the other leans mournfully on one hand. Up above, the angels are more jolly, youthful figures vigorously blowing trumpets. A flaming funereal urn is to each side.

The viewer can pick out symbolic references in the minor decoration. One cherub holds a skull, as a memento mori; the other holds an upturned torch to indicate life snuffed out; between them is carved an hourglass to show time run out. Larger carved panels show a skull and crossbones with a drape and wreath of olive leaves, and a winged flaming heart on its way to heaven, with crossed trumpets behind, and encircled with a snake swallowing its tail, a rather pagan symbol of rebirth or life eternal.

The monument has been attributed to the sculptor John Nost II (1712/13-1787), though like most of the other monuments given to this master it cannot be proven. Nost's uncle, John Nost I (Nost the Elder, d.1729) came from what is modern day Belgium to England to work for Arnold Quellin, married his master’s widow after his death, and became a significant sculptor to the nobility of the time, the bulk of his work being lead garden statuary. The younger Nost is thought to have trained under his uncle, but was apprenticed to Henry Scheemakers in 1726. His known works include several in Ireland, where he lived from 1750 to the early 1760s.

A monument as spectacular as this is rare, but there are other examples in London of figures like Josiah Child’s: Sir Andrew Riccard in St Olave Hart Street, John Bushnell’s figure of John Mordaunt in Fulham Church, or much nearer by, the Trafford monument in Walthamstow, all have similar stylish poses. Reclining noble Romans like Bernard Child include Sir William Hicks in Leyton Church; an even more flamboyant one outside London may be found in the statue of Sir Wiliam Gore in Tring, Herts. Everything else in the Church pales in comparison, but there is actually a good selection of panel monuments, including one with figure sculpture. We take them in date order:

Other 17th and 18th Century monuments:

Richard Captaine John Morice, d.1638, erected by his wife, Alice [Heydon]. A black inscribed panel, surrounded by a typical alabaster frame, with upper shelf, corbels at the base, and a central carving of a winged cherub head.

Mary Williamson, d.1683; the date given is 1682/3, given the January date. The inscription is carved as if on a hanging drapery, gracefully curved at the top and down the front, drop-folds to the sides, and a tasselled bottom edge, which is usual. At the top, left and right, are large winged cherub heads, with nicely carved flowery wreath in the centre, which would likely once have contained painted heraldic arms. At the base, the bottom of the drapery is hiked up over a lozenge of arms with frondy branches to the sides, and underneath this is a curly bracket, the scale highly suggestive that there was once more to the monument, perhaps much more. A worthy piece, and perhaps a progenitor to the carapace-shaped cartouches of a later generation.

David Petty, d.1745, and his wife Mary (Cookes) Petty, ‘By Whom He Left only one Daughter, // Married to The Rt Hon. George Leed CARPENTER, // Who Erected this Monument // To the Memory of the Best of Parents.” - though not best enough for her to record the date of death of her mother. A tall obelisk, with a massively gadrooned (corrugated) lower part bearing a shield of arms, crowned and with a trumpeting elephant carved on top, and with mantling, and with the base descending to the ground, obscured by modern furniture. The piece is signed by one of the great monumental sculptors, Peter Scheemakers.

Scheemakers' monument to D & M Petty, with Bacon's panel to Hannah Doorman.

Samuel Barlow, d.1746, and his wife Mary Barlow, d.1740, and Ann Barlow, d.1765, and Elizabeth Barlow, d.1770, these being the successive wives of Benjamin Barlow, who erected the monument in 1773. Large panel monument, with a highly colourful pinkish-brown and white streaked marble for the frame, and a thin inlay of white and black marble. At the top, a stone shelf surmounted by a thick pediment, also of stone, with relief carving of anthemion, stylised pots and tendrilous scrolling. The base, also in stone, hidden behind furniture. The use of coloured marbles was characteristic of many monuments of this period, and through until around 1800.

Sir John Hopkins, d.1796, Knight and Alderman of the City of London, his wife Ann, d.1806, and descendents through to 1834. An elegant broad oval panel, raised at the top to become the base of a pot, carved in low relief with delicate repeating patterns; a thin border of carved leaves to the upper part of the oval adds to the sense of delicacy. At the base, a painted shield of arms with crossed branches.

19th Century monuments:

Elizabeth Miles, d.1806. Designed as a casket end, with outward sloping sides, a lid with bobble on top, short legs underneath, and with a shaped black backing with an eared pediment. This has its own blocky supports, one signed by the statuary, Regnart of Hempstead Road.

Mrs Hannah Doorman, d.1807, with a verse beginning ‘Long by severest Ills She was opprest, // Yet never one Complaint escap’d her Breast: //She neither ask’d to live, nor fear’d to die. ...”, and ends more cheerily with her soul’s ascent to heaven – a presumption which an earlier generation would not have made so baldly, in verse or pictorial sculpture. The domed inscribed panel has on its apex a low relief carving of a wide funereal urn, and crossed leafy branches of olive and evergreen reaching round the curve, and at the base a lozenge of arms, ribbon and motto now broken, with low relief carving of a man with a heavy club and three deer. The curvy grey backing signed by the eminent sculptor and maker of funerary monuments John Bacon Junior, and dated 1812.

Susannah [Mangles] Warren, d.1814, with a convinced downward pointing spike at the base, reflected in the black backing panel. There are upper and lower shelves, and a plain triangle rather than a pediment. The very base of the backing panel has a small support carved as an opening flower.

George Bowles, d.1817, with a fine carving of a seated girl, mourning in front of a bust of the deceased. He is shown in absolute profile, a middle-aged man with swept back hair, a quite protruding nose, and a sense of purposefulness. The seated maiden is in Classical dress, eyes concealed in the drape she presses to her forehead, her other arm lying limply on her leg. The sense of dejectedness combined with the beauty of the figure and the delicacy of the drapery proclaims the work of an accomplished sculptor, and it is no surprise to find the signature of Chantrey on the side of the base. Francis Chantrey was one of the most prolific and certainly the richest English sculptor of the early 19th Century.

Joshua Knowles, d.1834, and his wife Mary Knowles, d.1844. A relatively ornate tomb-chest end. The sides bear low relief carvings of upturned torches, thus the extinction of life, and above the upper shelf, the lid contains carvings of flowers surrounded by swirls which becoming circles over the pilasters containing further flowers; the background is of Acanthus. Underneath, a small shield of arms, painted and gilt and with an elephant, and a carved ribbon over it. On a dark, shaped backing, signed by Richard Westmacott, London – presumably Sir Richard Westmacott RA, the most eminent and by far the most prolific monument maker of the family (but see this page).

Mary [Mangels] Cubitt, d.1836, sister of Susannah Warren above, with the same design.

The Revd. William Gilly, d.1837, Rector for 25 years. Carved as a tomb chest end, with upper shelf, fluted side pieces, and blocky feet. On a black backing.

Boswell Middleton, d.1840, a good white-on-black panel, with fluted side-pieces, moulded upper shelf, a draped pot on top, with acroteria bearing carved shells to the sides. At the base, a curved apron with a wreath and decorative ribbon, a space-filling device, and to the sides, leafy corbels. On a shaped black backing, signed by the mason, Sanders of New Road, Fitzroy Square. Competent.

Agatha Chapman, d.1840, ‘mother of twelve children... ten survive her’, with quotations. A tomb-chest end, quirkily cut with broad, low pediment, if such it can be called, and cut-outs to the panel below to form the little feet; the black backing likewise has cut outs.

R.M. Smith of King's Road, Chelsea: panel to T. Hodgson, d.1841.

Thomas Hodgson, d.1841, and his wife Mary Hannah Hodgson, d.1835. Panel with open pediment at the top and curly supports at the sides, and a central carving of a winged hourglass bordered by a snake swallowing its tail (picture at top of page), pagan symbol of eternity as seen on the Child monument. At the base, a narrow shelf with supports, and a central segment of a circle forming the apron, containing a carved shield of arms with a motto, and small bird on top. Signed by R.M. Smith, King’s Road, Chelsea.

John Saunders, d.1844, and wife Mary Saunders, d.1850. Another good monument, in the form of a casket end. Thus the central inscribed panel has pillar-like side-pieces, outward angled, under which are carved leafy termini forming the ‘feet’; a curved base is between. At the top, more of a lid than a pediment, on a shelf, with more unfurling leaves to the sides and a central double branch of olives tied with a ribbon, nicely carved to the scale. The sense overall is of careful proportion and sobriety: a second work by Sanders of New Road, Fitzroy Square.

Arthur Willis, d.1849, ‘of Oak Hall in this parish’, his wife Martha Anne Hall, d.1862, son Henry Hickley Willis, d.1856, and daughters Emily Willis, d.1832, and Lavinia Willis, d.1828. The order is puzzling, as the different blackening of the text suggests that the widow was added to the monument to her husband, and then the children, who died before her, added somewhat belatedly after that. Panel with blocky upper pediment and lower shelf, mouldings and brackets, on shaped black backing.

Elizabeth Chapman, d.1854, cut as a tomb chest end, with low lid above a thin, moulded rim, but no decorative carving. Signed by the prolific T. Gaffin, Regent Street, London. On a streaky grey backing panel with little block supports.

The Revd. Gerald Stephen Fitz-Gerald, d.1879, erected by the parishioners and friends, who also gave the Church font as a memorial. With heavy upper pediment bearing a coat of arms featuring a monkey (the Fitz-Geralds were an old and renowned family), Egyptianised leafy repeating decoration just below, and underneath the inscribed panel, an equally weighty base with two moulded brackets. The shaped black surround is signed by Underwood & Sons, Buckhurst Hill, N.E.

Thomas Quested Finnis, d.1883, ‘senior alderman of the City of London for 46 years’. Tall panel with pediment, acroteria, and a chunky base on two moulded corbels. The shaped black backing is signed by G. Maile & Son, Euston Road, London (who incidentally was the direct neighbour of the mason Sanders noted above; the road had changed name by this time).

Robert Sheaf, d.1894, Head Master of Wanstead National Schools for 25 years. Late Victorian reinterpretation of the Classical. an interesting composition, wilfully broad, the inscribed tablet sandwiched between thick shelves with mouldings; the thin attached pillars to the sides are deliberately undersized, and rather than the carved sections above and below we might have expected in mid-Victorian times, they are plain. Above, the pediment is reduced to a central pentagon in front of a horizontal slab, and carved upon it are pot, parchment and some brickish thing conceivably but probably not intended as a beehive (indicative of industriousness). The black backing is supported on two small brackets, one signed by a local statuary J. Looker of Wanstead.

We note en passant one 21st Century panel, to Peter Brown, d.2015, Churchwarden. A plain white panel with black backing.

J. Looker of Wanstead, panel to Robert Sheaf, d.1894. <

<

Modern brasses

There are several plain brasses of the 1900s and thereabouts. We may note:

Sir William Curtis, d.1829, and wife Ann Curtis, d.1833. An early brass panel of the type: the outer inscribed border includes repeating designs and Gothic windows, and is cut with an irregular outline; a rectangular projection at the top includes a cross.

Johanna Jacobina Curtis, d.1845, daughter Johanna Jacobina de Hubbenet, d.1845, and husband General William Frederick Curtis, d.1882. With the main capitals in red, and inscribed black line border with repeating floral patterning in red. A moderately ornate example of a typical style of the late 19th and early 20th Century.

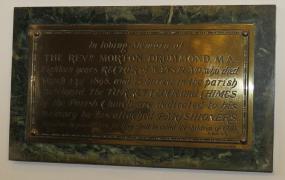

The Revd Morton Drummond, d.1898, Vicar of Wanstead, with nice text, a double line border, and a frame of serpentine. By Hart, Son, Peard & Co, Ltd, London.

John Scott, d.1906, Rector of Wanstead, formerly Prebendary of York, to whose memory the Churchyard Cross was also raised, with two shields of arms, and a wooden border.

John Reginald Corbett, d.1920, who held the living of St Botolph, Colchester for 32 years before being made Rector of Wanstead in 1907. Rather similar to the Drummond panel, with a wooden frame.

Also in the Church

The font, octagonal with festoons carved the outside of the bowl, which is of white marble, and supported on a cluster of four red-purple pillars, with a stone base of several stages; the wooden cover has a satisfying acorn. In memory of a Rector, the Revd. Gerald Stephen Fitz-Gerald, in post from 1864-1879 (see note above). The style suggests a design of the 1860s rather than the 1870s.

A grand pulpit, tall, wooden, on a single central pillar and with a hexagonal sounding board with inlaid starburst, and itself supported on a pair of thin pillars styled as palm trees. Exotic.

A wooden board listing Rectors of Wanstead from the 14th Century onwards.

Churchyard

To the side and behind the Church is the churchyard, with a fair crop of tombstones and more expensive monuments in a romantic setting. They include a good selection of different types of crosses: crosses fleury, Celtic and so on, along with one with a ship’s anchor, one with a decent angel standing in front of it and another with an angel clasping it [see this page for some examples of crosses]. Also notable are a series of chest tombs (big boxy monuments), and while the monuments are overwhelmingly 19th and early 20th Century in date, there are a few 18th Century headstones including for example with skull and crossbones. And amidst its smaller brethren stands one mausoleum-like structure, actually a sentry box, with domed top and acroteria - apparently marking the grave of Joseph Wilton (1722-1803), a fine portrait sculptor who was one of the founding members the Royal Academy.

View in Wanstead Churchyard, and mausoleum said to mark grave of the sculptor Joseph Wilton.

With many thanks to Wanstead Church authorities for permission to show pictures from inside the Church: their website is at www.wansteadparish.org/our-story/. The Church is open on Sundays for services, and on some Saturdays; it can be opened at other times for visitors by arrangement via the Parish office.

South-West to Leyton Church // or North-West to Walthamstow Church // Essex-in-London churches