Leyton Parish Church, St Mary the Virgin

Leyton Parish Church, St Mary the Virgin, is mostly 19th Century or later, but some of the fabric

dates from the 17th Century, notably the tower, and the monuments mostly predate the 19th Century work.

While the Church is of some antiquity, with one of the bells originally being 14th Century,

its history is that it started very small, and in several phases was effectively extended with aisles

on the side and additions at the ends until not much of the original remained.

The early 19th Century enlargement (1822) was by the architect John Shaw, with Thomas Cubitt as his builder.

War damage and repair led to the church we see today, which is bright and airy,

and still contains interesting early monuments.

This site does not usually note the people associated with the churches, howsoever eminent they may be,

but it must be said here that John Strype, the historian who published the most extended version of

John Stow s Survey of London, was a minister here for something like 50 years.

Sir Michael Hickes, Lady Elizabeth Hickes.

Sir Michael Hickes, Lady Elizabeth Hickes.

A small chapel now contains the two showiest of the monuments in the Church, to members of the Hickes family.

On the south wall is the lengthy monument to Sir Michael Hickes, d.1612, and wife Elizabeth, d.1635.

We see a pair of effigies of the husband and wife, in alabaster, with some painting,

almost foot almost to foot, against the wall, each leaning on a cushioned elbow, thus facing the viewer.

Early monuments with recumbent figures invariably have them on their backs, and later ones are often shown

in a relaxed side-on position, as if lounging Roman patrician style, next to the bath

see William Hickes below. But the Hickeses are shown in the sideways pose but stiff, he more so than her,

and would seem to be of the intermediate style, during which effigies were rolling over and sitting up,

as it were. We might mention George Snygge, d.1617, in St Stephen s Parish Church, Bristol,

as a similar stiff effigy.

Sir Michael Hickes is shown as a seemingly elderly man, in full armour, richly designed,

with high ruff on his neck and with a trimmed beard and moustache. Belted on his upward side is a sword,

or perhaps some sword-like staff, and in his hand is a small book.

His figure is slender. Elizabeth Hickes is in a black robe which envelopes her body in the usual 17th Century

way, and wears a broader ruff, a cowl, and has turned up sleeves. She too holds a small book.

She is shown rather younger than her husband. Rather more conventional than her husband,

were she a kneeling figure she could be slotted in without stylistic problems into many dozens

of other monuments of the period. Behind each figure is a shallow recess with inscription, and underneath,

a long table with two heavily carved coats of arms among decoration.

The monument has been moved twice originally against the east wall of the church,

it was moved to the south wall of the chancel when that was built in 1693, and in 1853 it was moved to

the current position. Apparently the monument was originally as an altar tomb but the parts rearranged later

if this is so, with the couple reclining next to one another, then it is hard to see how it could have

stood against a wall, as the inner recumbent figure would have been facing the wall.

William Hicks monument.

William Hicks monument.

Opposite in the chapel is the monument to Sir William Hickes, d.1702, erected in his own

lifetime. There are three figures, in marble this time: the recumbent one is his father, Sir William Hickes, Baronet, d.1680.

The standing figures are Sir William Hickes, and his wife, Lady Marthagnes, d.1723. Mrs Esdaile, the first modern writer who visited many English churches and described their monuments, apparently ascribed the work to an obscure sculptor called Benjamin Adye (another Adye, Thomas, is better known), but later writers do not seem to have credited this.

The reclining figure of the Baronet is shown as supremely self-pleased, and is certainly relaxed in his pose.

We note that his drapery, for he wears a long robe above his open waistcoat,

shows the downward force of gravity, unlike the case with the earlier figures noted above.

His many buttons are mostly undone up the chest, and around his neck is tied a scarf of some thin material.

He wears a full wig, and the sculptor has obviously taken some delight in the rendering of the curls,

as well as the sardonic expression of the portrait. The hands, too, are finely rendered, and in all,

this is a figure of considerable force and distinction.

What a contrast to the standing figure of the younger Sir William.

The first impression, unfortunately, is of the oversized head, which with the wig gives a considerable

and disproportionate mass. A shame, for the individual parts are good, as is the pose, which shows him in the

act of striding forward, one foot sideways, one forwards, upper body and neck progressively twisted

in the direction of movement, one hand eloquently on the breast as if declaiming, the other hand, damaged,

once presumably on the pommel of a sword. His face is upturned, eyes closed, aspect rather haughty, and apart

from the wig, he wears Roman costume, with armoured kilt and chest, swathe of heavy drapery around his torso,

over the arm and behind, and Roman open sandals. If only the head were a bit smaller.

The statue of Lady Marthagnes is more satisfactory. We see a Classical figure,

Roman baroque, though with certainly not a Classical face, standing with one knee bent,

with in one an open book, the other raised, palm out. She is wearing a cowl across her head,

and generally rather thin drapes except for a heavier twist from her robe which goes across her front,

around her arm, and then hangs in graceful folds to her side. A sad, rather unflattering expression,

and the neck too columnar, the treatment of the hands however being excellent.

Her drapes fall to the ground so we cannot admire her feet. The composition as a whole,

with the two standing figures flanking the reclining one, is good, and incorporates a broad oval window behind.

Now to the rest of the monuments:

17th Century:

- Andrew Redich, d.1605. The earliest wall monument in the church, alabaster,

with fluted side pilasters, broad upper and lower shelves with entablatures, and on top a coat of arms

with carved surround, flanked by two small pots. At the base, a shaped apron.

- Charles Goring, d.1670, Right Valiant Comander, Baron of Hurst Perpoint,

and Earle of Norwich . The pale marble panel is surrounded by a dark border and lower shelf,

with recessed outer pilasters with scrolling at the base, with some emergent floralities climbing up

the pilaster shaft, to where on the outer edge some further vine hangs down from the leaf covered capitals.

At the top, a most flamboyant shield of arms, supported by two fierce rampant lions.

At the base, a further coat of arms with carved leaves on the apron.

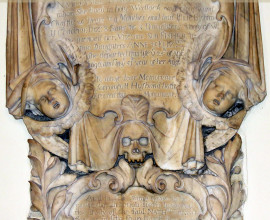

- Anne Tench, d.1696, erected by her husband Nathaniel Tench, d.1710.

A different type of wall plaque, as a cartouche, or more properly double cartouche.

The upper, main portion of the monument has the inscription surrounded by scrolls and hanging drapery,

knotted in conventional fashion at top right and left, and depending from above a shield of arms with a dog

or deer s head on top. At the base of this, two cherubic heads amidst the drapery, and centre,

a grinning skull. The monument has been carefully extended downwards with a second cartouche,

closely fitted into the base of the first, rather shallower, but in rather similar style, to the husband.

Again surrounded by a border of scrolling, but no drapery

instead two branches of mistletoe form the outer boundaries.

At the base, a single bracket with Acanthus, which may have had the initials of the sculptor.

Anne Tench, d.1696.

Anne Tench, d.1696.

18th Century

- Newdigate Owsley, d.1714, and children Catherine, d.1709, Newdigate, d.1714,

and Elizabeth, d.1721. The veined marble inscription surrounded by a grand monument

in brecciated slatey coloured marbles. To the sides, two full Composite pillars,

supporting a broken curved pediment enclosing a large shield at arms in a cartouche.

The ends of the sides of the pediment are capped with flowers. Between the curved top of the inscription

slab and the entablature, a pair of low relief skulls have been placed as memento mori.

At the base of the monument, the rather solid apron bears three cherubic heads, their wings overlapping,

with further scrolling, and an acanthus corbel at the base. Rather a grand baroque composition,

signed prominently by the sculptor, S. Tufnell.

- William Church, d.1723, and wife Mary, d.1707, and family to 1733.

Rectangular panel with frame and upper and lower shelf so thin that the whole piece has a rather spare,

austere effect, despite the upper jelly-mould pot, two flaming conches, one missing its carved flame,

and at the base a broad-winged cherub head.

Newdigate Owsley, d.1714, by Tuffnell, and Richard Hopkins, d.1735.

Newdigate Owsley, d.1714, by Tuffnell, and Richard Hopkins, d.1735.

- Sir Richard Hopkins Knight, d.1735, and wife Dame Anne Hopkins, d.1759,

who erected the monument. With Doric side pillars in brecciated grey marble, supporting entablature

and curved broken pediment enclosing a cartouche with arms, all this being nicely proportioned.

The basal shelf, however, has its centre absent, to allow for a sort of tongue of marble to project downwards

over the narrowing apron, and as the remaining parts of the shelf below the pilasters bear a wavy,

almost shell-like repeating pattern and have depending from them bell-shaped supports,

the unfortunate effect is of two stumpy, clawed legs. At the base, a winged cherub head.

- A monument which I could not read, also based on a rather splendid cartouche with side drapery,

and underneath, crossed sword and mitre with linked chains, nicely carved.

At the base of the cartouche is a grotesque face.

- William Bowyer, d.1737. A plain white slab with long Latin inscription, with thin shelf below,

and curvy at top and bottom but no other adornment.

- John Strange, d.1754. Another rather grand edifice, almost shrinelike in its presentation.

The central inscription, on a white panel with rounded top, is surrounded by a border of coloured alabaster,

with a carved shell and acanthus at the top, then a thin second border with carved repeating pattern which

coils round into scrolls at the base, then a broader, recessed backing which itself has a low relief oak leaf

design upon it at the sides. All this rests on a thin shelf, decorated with further repeating patterns,

above a baroque shaped apron with three cherubic heads in the centre, nicely composed,

and with three leafy brackets or corbels. At the top, an open pediment, again with carved repeating

decoration and recessed sides, encloses a cartouche of arms, now blank, and at the very top,

an elegant plump pot with garland of flowers and leaves, hanging down to each side, without any backing;

Horn-shaped flaming lamps to each side. The effect of the whole, with its ornate carving

and colourful marbles and alabaster, is of extreme richness. The work is apparently by Henry Cheere,

which is entirely plausible, as the style of vase, cartouche and other details is similar to other

of his monuments, for example the Medley Memorial in York Minster.

John Strange, attrib. Henry Cheere, and Thomas Hawes, by John Annis.

John Strange, attrib. Henry Cheere, and Thomas Hawes, by John Annis.

- Thomas Hawes, d.1685, wife Elizabeth, d.1727, and offspring Elizabeth, d.1704,

Nathaniel, d.1712, Thomas, d.1743, and Anne, d.1759.

With brecciated marble pilasters, rather chunky, and equally chunky pediment, more a gable,

the angle is so steep, broken at the top and enclosing a cartouche at arms.

On each side, a cherub reclines, each holding a handkerchief.

At the base, central and side supports with floral carving. By the sculptor John Annis.

- Samuel Bosanquet, d.1765, and wife Mary, d.1765.

Another grand monument, the inscription with a dark yellow border, and to the sides,

scrolled pilasters with relief floral decoration. The upper shelf supports a tall obelisk in dark marble,

with a border of white and red, and upon it a shield at arms with floral surround and the usual knight s helm.

At the top, a small base would once have held a pot or lamp. On either side of the obelisk are fluted pots.

The shelf below the inscribed slab has repeating shell moulding,

and beneath this is a panel with relief carving of three cherubic heads,

with a profusion of overlapping wings. Such obelisk or pyramid designs are fairly widespread

in the latter half of the 18th Century. The monument is signed it looks like J. Pafc, but the

f is an s , and there is a missing final letter, thus J. Pasco.

Pyramidal composition: Samuel Bosanquet by J. Pasco, and statue from John Story monument by John Hickey.

Pyramidal composition: Samuel Bosanquet by J. Pasco, and statue from John Story monument by John Hickey.

- John Story, d.1786, another pyramidal composition, with the backing pyramid running behind

the whole monument from the bottom, making the main structure look somewhat like a fireplace in front of it,

with its central blank face and little hanging drape. But this forms but the base for a sculpture of a girl

angel, rather Baroque, with a leaning pose and confident swirls of drapery about her thigh and lower leg

and across her torso. Her face is of the 18th Century, as is the style of the arms,

which are however very graceful, especially the flex to the wrist and the pose of the fingers around the pole

she holds in one hand. She is of the girl with pot type, and her pot is a tall,

rounded one on a narrow stem, with upon it an unrolling scroll with the monument s inscription.

The sculpture projects from the backing enough that we can appreciate it from different directions,

and it is seen to advantage from any of them. A very competent work by the sculptor John Hickey of London.

19th Century, and one 20th Century

- John Hillersdon, d.1807, infant brothers Edward Harcourt Hillersdon,

and William Bard Hillersdon, and sister Charlotte Ann Hillersdon, d.1781,

highly recognisable as the work of John Flaxman, and signed by him.

Above the inscription on a simple panel is a seated girl, reading a book.

She is utterly classical, with Roman nose, pure face, rather muscular exposed arm, and perfect feet.

She is dressed in a fine drape that starts from her crown, sweeps own around her shoulder,

and is caught in loops across and under her thigh, with a hem above the ankle.

The viewer is captivated at once by the repeating curves, and that of the youthful figure revealed

by the thin drapes. A noble and harmonious work.

Works by John Flaxman: William Bosanquet and John Hillersdon monuments.

Works by John Flaxman: William Bosanquet and John Hillersdon monuments.

- William Bosanquet, 1813, second son of Samuel and Mary Bosanquet, already encountered above,

another work by Flaxman, this time less obviously so.

The monument is based on a carved panel depicting the Good Samaritan. The central figure is the Samaritan,

shown in relief, stooping to place a hand on the shoulder of the collapsed figure by the wayside,

his other hand holding a bowl of water to bring relief. To the right, his donkey eats some cabbagelike plant,

and behind two clerics walk past unheeding. A clever composition unsymmetrical,

but balanced by the similar masses in each half of the panel, and with biding diagonal lines from top left

to bottom right, and top right to bottom left.

- Joseph Cotton, d.1825, and wife Sarah, d.1818.

One of the typical white panel on a black backing panels of the period,

with however rather nicely carved anemone acroteria and central ornament.

- Revd Charles Henry Laprimaudaye, d.1848, and wife Jane, d.1849.

A plainer white-on-black panel in the shape of a tomb chest end.

- John Lane, d.1852, wife Elizabeth, d.1852, and daughter Florence,

d.1851. The white marble panel includes a small recessed oval with a carved flower, perhaps a bluebell,

with its stem snapped, indicative of the young life being ended. With black frame, upper shelf,

and two brackets.

Henry Weekes's monument to Mary Anne Innes, d.1853.

Henry Weekes's monument to Mary Anne Innes, d.1853.

- Mary Anne Innes, d.1853. White tomb chest end on a backing of grey, streaked marble,

but with some carving in the shape of an asymmetrically draped fluted pot on top,

and reliefs of two upturned torches. Signed by Henry Weekes in the same year.

This prominent sculptor made a number of funereal monuments,

including the full length effigy of Archbishop Sumner for Canterbury Cathedral,

and the dramatic Shelley monument with a charming girl cradling the expiring poet in her arms,

but is best known for his busts and public statues, of which the most prominent is his group of Manufactures

for the Albert Memorial.

- Sarah Sidney, d.1857, wife of Thomas Sidney of Leyton House.

The panel, as a tomb chest end, includes at the top a nice carving of a crossed sword and mitre

with thistle shaped crown above, with a ribbon swirling around them enscribed Domine Dirige Nos .

On the lower shelf is a small coat of arms with a ribbon with the motto Gratias Deo agere ,

thus God, direct us and Give thanks to God . The signature is almost worn away and indecipherable.

E. J. Brewster, by Gaffin.

E. J. Brewster, by Gaffin.

- Edward Jones Brewster, d.1898. An ornate late Victorian monument.

The long inscription to the former Vicar of the church notes that he was nephew to the Lord Chancellor of

Ireland, worked in the law before becoming a cleric, and was himself born in Dublin,

and died in Cape Town, South Africa. The main feature of the monument is a relief of a girl mourning

over a pot. She is classically draped, and has her hair drawn up in some sort of bun at the top,

while still leaving a stray curl over her neck. Unlike the typical composition of the earlier part

of the century where the girl is standing and leans on the pot, her she kneels by it, as if praying to it,

with one arm clasped possessively around the body, the other around the unseen neck,

with her head resting upon it. Little flowers adorn the pot, and a fallen olive branch is at its base.

The work is better in as a while than in the detail, for her lower leg is too long, her hand against the pot

vague around the thumb, and the bun of her hair a bit too regular,

while the drapes around her middle give her a slightly barrel shape. But the face is nice,

and the composition original. Most surprising is the sculptor, Gaffin of Regent Street, London.

This is a late fairly work for the firm, which flourished from the 1820s,

and while their work is found all over the country, mostly it is among the most simple

of shaped white tablets on black backings, with a minimum of carving.

So a full figure is quite a treat.

We should mention that the monument includes a curved pediment with anemone patterns and flowers,

and a central crown, and at the base is further carved scrolling with a motto. Interesting.

- Sarah Jane Cranston, d.1943. The most recent monumental tablet as a rather plain stone panel.

On either side of the chancel is an outdoor tombstone brought indoors,

to Sir Thomas Want, d.1785, and Thomas Want Jr, d.1789.

Each has a low relief carving at the top, of a flying angel, male, the one holding a flower and ribbon,

the other a small figure, presumably a soul.

We may note a few fragmentary ancient brasses, to Elizabeth Wood, d.1626

and husband Toby Wood, with a number of inscribed figures, a single figure of a standing female,

praying, with long hair, an inscription to Sir Edward Holmeden, d.1598 and his wife,

Elizabeth, and one long inscription dated 1557.

Also a number of 19th century revival brass memorials, characteristic of the times,

for example to James Innes, d.1874, shaped as a trefoil window, with ornamental black lettering,

and a border and top in red and black, showing leaves and flowers.

There is in the church, apparently, a font dating from the 15th Century, apart from the pedestal,

but I would not have assumed that the octagonal one which I saw was medieval.

Finally in the interior, we should note two small stained glass windows from the 1930s,

gifts to the children of the Parish, showing seated girls or female saints,

nicely done and in beautiful glowing colours - one is pictured above.

There is a goodly sized churchyard, particularly extending to the rear with some ancient cottages alongside. Among the usual

headstones are a couple with figures, various tomb chests, and the odd more architecturally significant tombs,

as shown below.

18th Century tombs in the churchyard.

18th Century tombs in the churchyard.

Grateful thanks to the Church authorities for permission to use pictures from inside the Church: their website is at

http://www.leytonparishchurch.org.uk/welcome.htm.

Top of page

Essex-in-London church monuments

Just south to Leyton Town Hall

Nearby Walthamstow Church (2 miles north) // and West Ham Church (1 1/2 miles south) // East to Dagenham Church // and then Hornchurch

Also South, to former Passmore Edwards Museum // or along Romford Road

Monuments in some London Churches // Churches in the City of London // Introduction to church monuments

Angel statues // Cherub sculpture //

London sculpture // Sculptors

Home

Visits to this page from 3 Nov 2013: 10,618

Sir Michael Hickes, Lady Elizabeth Hickes.

Sir Michael Hickes, Lady Elizabeth Hickes.

Newdigate Owsley, d.1714, by Tuffnell, and Richard Hopkins, d.1735.

Newdigate Owsley, d.1714, by Tuffnell, and Richard Hopkins, d.1735.

John Strange, attrib. Henry Cheere, and Thomas Hawes, by John Annis.

John Strange, attrib. Henry Cheere, and Thomas Hawes, by John Annis.

Pyramidal composition: Samuel Bosanquet by J. Pasco, and statue from John Story monument by John Hickey.

Pyramidal composition: Samuel Bosanquet by J. Pasco, and statue from John Story monument by John Hickey.

Works by John Flaxman: William Bosanquet and John Hillersdon monuments.

Works by John Flaxman: William Bosanquet and John Hillersdon monuments.

18th Century tombs in the churchyard.

18th Century tombs in the churchyard.