St Olave Hart St, City of London, and its sculptural interest

St Olave Hart Street, with gateway.

The little City Church of St Olave Hart Street has a small but interesting and important collection of monuments from the 17th Century. The building itself is largely 15th Century, and retains an intimate, medieval atmosphere. Definitely worth a visit if in the area; it is very close to Fenchurch Street.

St Olave (Olave or Olaf Haraldson) was an 11th Century Norwegian who fought on the side of the English (Saxons, then, under Ethelred) against the invading Danes. He returned to become King of Norway, and apparently fell after promoting Christianity too vigorously for the tastes of his countrymen. The church we see today is largely 15th Century, but underneath, though I have not seen it, is a late Norman crypt, from the 13th Century, and within it the remains of a more ancient well which would presumably have been from the Saxon building once on this site. The church escaped the Great Fire, but was damaged in WW2, and was restored by Glanfield in the 1950s, who added the south porch.

Our best view of the exterior is from the corner of Seething Lane and Hart Street. We can see 15th century stonework and windows, and some more modern exterior cladding which will look fine in a hundred years or so, and the brick upper part to the little tower, which dates from 1731-2, by the architect John Widdows, according to Pevsner. On the Seething Lane front is the entrance gate to the tiny churchyard, a macabre construction with three skulls in the pediment and two more on the corners, dating from 1658. Back round the corner in Hart Street, the modern frontage round the entrance has two spandrel figures of angels with trumpets, and next door, on the Rectory, built in the 1950s replacing an 18th Century building lost to WW2 bombing, is a modern stone panel depicting King Olave with axe etc, and a head by his feet.

Inside, the church gives an instant impression of medieval closeness, a little cramped, with many monuments and furnishings to see, a warmly coloured oak ceiling (a modern copy, I believe, of the destroyed original), most of the floor filled with pews, and clustered columns of some ancient limestone separating the narrow nave from the aisles. Pevsner suggests these pillars are probably reused from the 13th Century church. Most of the furnishings survived WW2, including the 17th Century pulpit from St Benet Gracechurch Street, attributed tentatively by some to Grinling Gibbons, the panelling, and sword rests.

Andrew Riccard, and by comparison, Lord Mordaunt in Fulham Church (see text).

The monuments are significant, including those to the famous London diarist Pepys and his wife, and various other 17th and 18th century personages, among whom is a high official of the East India Company. We note several of them, starting with the latter:

- Sir Andrew Riccard, a standing figure in stone, A Citizen and opulent Merchant

of London often chairman of the East India Company,

18 years chairman of the Turky Company , d.1672. It was he who bequeathed the patronage of

the church to the parish. There are separate Latin inscriptions below the main one. The

statue is of pale stone,

stained, with the figure shown standing rather than kneeling, his legs turned outwards or

even crossed under his thick classical robes.

One arm is raised as if orating, but seems to have held some item with a handle rather than

a scroll. He wears some decorative circle

of fabric round his neck, perhaps connected with his august offices. His head is slightly

upturned, and this with his curled longish

hair, moustache, and little beard, gives him a heroic look and a certain panache an

accomplished work showing a larger than life

character. The work was attributed by the writer on sculptural monuments, Mrs Esdaile, to John

Bushnell - this must be on the basis of the closeness of the pose to that of Lord Mordaunt in Fulham

Parish Church - see pictures above.

John Bushnall was an important sculptor of the period, with few firmly attributable works

surviving - but see Mrs Pepys's monument below.

Kneeler monuments, time of James I.

- Andrew and Paul Bayninge, two brothers: Andrew Bayninge esquior, sometimes

alderman of London, lived to the age of 67 yeares and

dyed the 21st of December Anno Dom 1610. Paule Bayninge Esquior, sometimes sherriffe and

alderman of London, lived to the age of 77

yeares and dyed the 30th of September Anno Dom 1616. The kneeling, praying, painted figures

both face the same way (rather than towards each other, which is generally reserved for

married couples), the monument

occupying a corner position so that they are oriented in different directions. With their

red robes over black, golden ruffs and

highlights, and large marble or alabaster surround with Corinthian pillars and

accoutrements, the effect is sumptuous and rich - see picture above left. The

skulls on top are particularly macabre. More on kneeler monuments on this

page.

- Jacob Deane d.1608, and wife. Another large, flamboyant early 17th Century

monument, very colourful, shown above right. The couple kneel praying,

facing each other over a prayer table in conventional fashion for such monuments. She wears

a bonnet, a rich ruff, above her black

robes and dress, while he wears armour of dull gold highlighted in red. The two swaddled

infants below centre, resting on a skull,

indicate two children who died soon after birth. Female figures to left and right, both

facing left, are shown in similar dress

but slightly smaller these are the two previous wives, one of whom also had a child who

died. There seem to have been no surviving

offspring. Much by way of armourial bearings, skulls, cherubic heads and other decoration

around, all very grand.

- Samuel Pepys 1632-1703. The original monument 'of his own making' (i.e. design)

is lost, and that which we see is from 1883, erected by public subscription mainly

owing to the efforts of Henry Benjamin Wheatley (1838-1917), editor of the complete edition of

Pepys diary, as noted on an inscription at

the base. The monument consists of a bewigged bust of Pepys in high relief in an ornate

surround, almost like a fountain against the

wall, with cornucopias, thick Corinthian pillars, above a broken pediment with pot and

eternal flame, and below, arms surrounded by

three winged cherub heads, coming a bit forward supported on Acanthus leaves, to suggest a

supporting boss.

17th Century - John Bushnell's monument to Elizabeth Pepys.

- Elizabeth Pepys, d.1669. Of more artistic importance than the monument to Pepys

is that of his wife, It comprises a pale bust

against a black roundel, leaning outwards. She is shown as a woman with a round face,

headdress under which her hair peeps out in an

early German style, with curls left and right hanging free of her long, slender neck, almost

like a Durer picture. The drapes are

classical, again with a nod to Durer, and enough body shown that the drapes almost suggest

arms coming together in prayer.

A well composed work, known to be by the sculptor John Bushnell. The Latin inscription

below is

surrounded by a cartouche, on which rests a mantel with a short plinth supporting the

portrait, and two outward-turning skulls.

A cherubic head is to the left under the mantel, but the one to the right was lost many

years ago. In more recent times, there was still

a diamond-shaped backing to the monument, with curved, concave sides, but this too has gone,

leaving the bust in its niche rather separate from the rest of the monument.

- Peter Cappone, d.1582. A kneeling upright figure in brown stone wearing a

knight s armour, and a stiff necked ruff, rather haughty

in appearance - see picture at the bottom of this page. Above, a pediment supported on

Corinthian pillars.

- Sir John Radclif (Radcliffe) d.1568 and Lady Radclif d.1585. His statue,

mounted on the wall, is a praying figure with

legs lost below the thighs, and one hand missing (that was later damage, in WWII). He wears

his suit of armour and his sword is behind him, or rather beneath, as this was

a recumbent figure, as noted by Stow, the 1600s topographer of London, which has been

remounted vertically. His expression is rather sad. Lady Radclif's effigy, once beside the

altar

tomb of her husband, shows her kneeling on her cushion, with her hands clasped in prayer in

the usual manner.

- Elizabeth Gore, d 1698 aged 18 years and 11 months. A small high up

wall-mounted roundel with a portrait bust and inscription below

surrounded by narrow symmetrical drapes, and a heraldic shield below that. A plain, perhaps

damaged and over restored, face, curly hair,

long and wavy at back, classical drapes to her cloak, which is clasped under her breasts.

She wears a thin undershirt beneath.

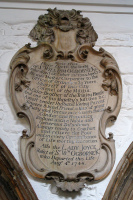

18th Century - cartouche to Sir William Ogborne, d.1734.

- Sir William Ogborne, d. 1734. Knight, master carpenter to the Office of

Ordnance, Sherriff to the City, Colonel of the Militia,

Elder Brother of the Trinity House, and one of his Majesty s Justices &c. Also Lady Joyce,

relict of him, d.1744. A cartouche with

baroque surrounding swirls, a blank small shield above with helmet, and little shell at

base.

- Rev. John Letts, rector, d 1857, a charming small monument set in the wall, like a little three-light window, with two mottoes in black against a white panel down the side lights, and two little pillars.

The church also holds some notable brasses from the 18th Century, but these are not the subject of these pages.

With thanks to the Church authorities for permission to include photos from inside the church; their website is http://www.sanctuaryinthecity.net/St-Olaves.html.

16th Century - Peter Cappone monument, d.1582.

Go west and north up Mark Street to the tower of All Hallows Staining // Or north to St Katharine Cree // or St Gabriel's churchyard // and thence to St Andrew Undershaft