St Mary the Virgin, Walthamstow, London/Essex - Monuments

St Mary Walthamstow, now part of north London, anciently in Essex (see this page), is a little away

from the modern centre and Hoe Street, and has enough trees around it that it needs to be seen

in winter to view it properly. It is all of a piece, beige cement over brick, five bays

to the nave with a south porch, and a low, buttressed and embattled tower with a

corner newel tower. The majority is of c.1535, mostly at the generous expense of two rich men:

Sir George Monox [Monoux] and Robert Thorn [Thorne], who founded the Grammar School,

and endowed almshouses nearby. A late 18th Century account said that by that time, there

had so many repairs that there was little of the original, 12th Century Church to be seen.

Vigorous 19th Century refurbishments in 1817, 1843 and 1876 obliterated most

remaining original features inside and out. So while the outside is not so exciting

one popular 1900s guidebook dismissed it as being as devoid of architectural interest

as could be wished by the most austere of Puritans , inside we have fine Victorian features,

with tall arcades on slender pillars, a long gallery on one side, and wooden ceiling and pewing,

all well matched, and because of the several tall pillars, giving an interesting and

explorable space. And the monuments which we have come to see are everywhere along the walls,

in the gallery, and on those pillars one pillar has no less than five panels clustered upon it.

St Mary the Virgin, Walthamstow: exterior and interior views.

Monuments

An important collection. There are something like 60 monumental panels,

and two magnificent tombs of the 17th or early 18th Century with figure sculpture.

Among the panels there is a bit more figure sculpture from the 19th Century,

and a plethora of different shapes, making this a most representative collection of works

from the 17th Century through to the 20th. The two grand early monuments include one by

Nicholas Stone, most prominent among early English sculptors, and the other perhaps by

William Cure the Younger. Later pieces by significant sculptors include a figural work by

W.G. Nicholl, a Bacon and Manning tablet, and a simpler panel by Sir Richard Westmacott RA,

and various 19th Century stonemasons are represented, including M.W. Johnson, Theakston of Pimlico,

Bedford of Oxford Street, Burke & Co of Newman Street, and Brown of Great Russell Street.

We start with the two grandest monuments, and then take the rest in date order.

Lady Lucy Percy Stanley, d. circa 1630

Lady Lucy Percy Stanley, d. circa 1630. Her statue is kneeling

in front of her prayer stool, under a tall, arched canopy. Above are

two smaller female statues, and below, two more. She was the wife of Sir Edward Stanley, and daughter of the Earl of Northumberland.

Lady Stanley is shown with an astonishing hairdo, beautifully carved, arched above her forehead,

and with a coronet behind. Her face is young, rounded and modelled to show the delicate play of

muscle and bone around the cheek and jaw. Around her neck is a wide ruff sticking out considerably

behind. She wears some thick-sleeved garment over a vest, low at the front to push up her

rounded breasts, emblematic of her

fruitfulness in producing seven daughters. A many-stranded necklace falls to her

waist from under her ruff. Her hands are lost, but would have been in an attitude of prayer.

Below, she wears a many-pleated skirt, and over all she wears a cloak and mantle,

thrown back to expose the shoulder. Her kneeling pose is perfectly upright, demonstrating youth

and vigour.

Lady Lucy Stanley, d.c.1630, perhaps by William Cure the Younger.

There are bars in front of the monument, so the pair of female figures at the base

presumably two of the daughters are less easy to appreciate, but unlike their mother,

they are rather simply made, or just painted too thickly. They wear similar hairstyles and ruffs,

in miniature and without the detail, and have plainer clothes, wider stays and so an odder

profile to modern eyes. Between them is a prayer desk, as normal on such monuments.

The small figures at the top, one headless, are similar but are full free-standing statues:

they would at one time have been to the side of the monument (which has been moved),

as it would be unusual to put them at the top, and certainly not praying to the family coat

of arms. All four, like their mother, rest their knees on the tasselled cushions that were

de rigour in kneeler monuments of the time (see this page). Between the two at the top is a painted shield

of arms in a roundel, with perhaps some small amount of missing strapwork.

At one time ascribed to the sculptor Nicholas Johnson, or his circle, more recent attribution

of this excellent sculptural monument has been to William Cure the Younger.

He was an important sculptor working from at least 1605 to the early 1630s,

making Royal fountains and architectural sculpture as well as statues and monuments.

The attribution is on the basis of the style of the central figure of Lady Stanley

and the way the face is sculpted, comparing to Cure s documented monument to Sir Roger Aston

and his family in St Dunstan, Cranford, Hillingdon.

Dame Mary Merry, d.1632, and Thomas Merry, d.1654

Dame Mary Merry, d.1632, and also commemorating her husband, Thomas Merry, d.1654,

so made while he was still alive. There is a long inscription and eulogy to her,

but the inscription to him was never added as intended. But. An important memorial

by Nicholas Stone the Elder, an early English sculptor. The alabaster monument

centres on the busts of the couple, above the main inscription, each in an oval niche.

Unpainted alabaster, they are much more sympathetic and with more personality than had

they been painted. She has a thoughtful, late middle aged face, curly hair to the sides,

a cap on top, the head resting on one of the vast ruffs favoured in Elizabethan times.

Her clothing is much padded in the arms, so that her head looks small on her.

One hand rests on her chest, the other cradles a jawless skull, indicating her demise,

unlike her husband, who holds a book. He has a long, calm face, narrow nose and high cheekbones,

curly hair and a short beard. His smaller ruff is somewhat downturned, and he wears plate mail

armour. As noted, one hand holds a book, a finger inserted as he is only part way through it,

and, allegorically, only part way through his life. His other hand cradles this hand from

underneath, a clever way to show the slight weight of the book, and suggests the pose was

captured from the life.

Dame Mary and Thomas Merry, 1633, by the sculptor Nicholas Stone the Elder.

The spandrels (triangularish spaces) around the ovals are filled

with low relief carvings of stylised foliage, with a winged cherub head at the top in the centre.

To each side of the main inscription is a panel with relief portraits of two figures,

who would be the offspring of the couple, by convention with the girls, youngish women

with similarly curled hair but with necks exposed and wearing necklaces, underneath their mother,

while the sons, with long hair, moustaches and differing collars, under their father.

More inscriptions are underneath, including the blank space intended for Sir Thomas.

At the top of the monument is an entablature, then a shelf with a curved pediment, open at the top

to insert an oversized coat of arms, with its own pediment on top, very baroque.

On the curved sides of the pediment sit two reclining girls, one of whom has lost her head

and a hand, the other her hand and part of her support. But what excellent figures they are

in rather Classical robes, down to the ankles of the bare feet, wide sleeved,

but with the tops folded down to expose their breasts, relaxed and easy in pose.

The one with the head shows a youthful but non-idealistic face, plump in the cheek,

narrow in the nose, mouth awry, and it is hard to imagine that this sort of face would have

been given to what must be an allegorical figure in later times. An important work of art

by the most accomplished of early English sculptors. Nicholas Stone kept careful notebooks

which have survived noting nearly all his commissions, so we know this monument was executed

in 1633. It has been altered, and, it is thought, has been cut down at the sides.

Stone, born in England in 1586/7, was trained in part by Hendrick de Keyser in Amsterdam,

and became a highly successful sculptor back in London from the 1610s through until 1642,

when the Civil War abruptly curtailed his career. He made many surviving Church monuments,

as well as statues and architectural sculpture, and had three sons who became sculptors,

including Nicholas Stone the Younger.

Merry monument: portraits in relief, and reclining Classical girls.

Susannah Trafford, d.1689, and Sigismund Trafford, d.1723

Susannah Trafford, d.1689, and husband d.1740, Sigismund Trafford, d.1723.

A grand monument indeed, with the figures of the deceased couple standing on either side

of their daughter, a small child, on top of a long, mantelpiece-like tomb chest. Behind them,

the monument rises to a massive entablature raised on receding side pilasters,

like some great fireplace, rather overpowering the figures in front, and above this are seated

a pair of mourning cherubs leading against a central urn. The figure of Sigismund Trafford

stands in 18th Century mannerist fashion, one hand raised, the other gesturing eloquently

at his chest, face slightly upturned, pose with one leg forward, the mass of the body falling

on the other hip and leg. He has a full periwig, rather incongruously matched with the rest

of his costume, which is that of a Roman solider, with armoured kilt and short sleeves,

and either a naked chest and stomach or more likely a cuirass moulded to show the musculature

underneath. His cloak is swept back in dashing style. His face is old, grim-faced and proud,

his nearer arm powerful and hand expressive. Below, equally powerful legs protrude from

Roman boots with rolled-down tops.

Monument to Susannah Trafford, d.1689, and Sigismund Trafford, d.1721.

Susannah Trafford is a more conventional Roman figure, standing fairly symmetrically,

but head turned inwards on the long, columnar neck, her arms across her lower chest

with one hand pressed upon the other expressing her heartfelt sorrow. Her face,

like her husband s, is of its time rather than being Classical, and she has the feminine

roundedness without much musculature favoured in the later 17th and 18th Centuries.

She wears a thinnish robe, tied at the waist and with sleeves gathered above the elbow

and tied with a button. The robe clings round the legs, showing her slender form, and her feet

are bare.

Susannah Trafford and child.

Between the couple is the statue of their small child, kneeling on a stand with winged cherub

heads at the base. Her clothing is simpler, some smock with a bit of drape over one knee

and caught up on the arm, but again the hair puts her far away from Classicism.

The sides of the architecture behind and above them are decorated with beautifully carved

and undercut flowers and fruits, and there is a tied drape above.

Above this a painted shield of arms on a cartouche, which is just below the summit pot.

The two naked cherubs are typical of the breed, all plump faces and knees, one with a

handkerchief pressed against his face, the other with arm apparently behind the pot,

and a drape just off the shoulder; unless it is damaged and there was drapery against

that face too. Two urns to the side of the principle figures complete the ensemble,

and the hard-to-read inscriptions are below on the mantelpiece-like altar tomb below.

Rest of the Monuments

17th Century Monuments

- Henry Birchenhead of Walthamstow, d.1656, with a Latin inscription.

The inscribed panel is surrounded with a broad marble frame carved as very full hanging draperies,

with a shield of arms surrounded by scrolls above. The drapery starts from behind the helm on top

of the shield, is pulled towards knots at the top sides, then hangs in part freely downwards,

and in part stretched behind the inscribed panel, and then hangs fairly flat at the base;

great confidence is shown in the distribution of folds, which is utterly convincing.

At the top sides are two cherubs, shown as half figures emerging from behind the knotted drapery.

17th Century panels: Henry Birchenhead and Henry Maynard.

17th Century panels: Henry Birchenhead and Henry Maynard.

- William Conyers, d.1659, black panel with hard to read script,

a lot of it, and recording other members of his family. This is surrounded by a pale marble frame,

with a shelf at the top, and one below, beneath which is a broad apron or lower panel

decorated with memento mori a central skull, an hourglass, and gravedigger s tools.

- Henry Maynard, d.1686, and noting relatives including

Charles Maynard, d.1665. Described as principal benefactor of the parish .

A substantial mural monument, with the long inscription on a domed panel, with receding,

fluted pilasters at the sides, in front of which stand two plump cherubs or putti.

They stand in histrionic pose, being almost mirror images of each other,

each with one hand across his breast, in a gesture of mourning, and the other hand

of the one clasping an upturned torch symbolic of the extinguishing of life.

The other has the broken handle of what may have been a similar upturned torch.

At the tops of the pilasters, thus above the cherubs, are flaming urns, flamboyantly carved.

On the top of the arch of the central panel is a larger pot, light-bulb shaped, with a

very small flaming urn on top of that. At the base, a shelf with two curly brackets supporting it,

and between them, a small shield of arms with two frondy branches around it;

there is a black backing to this lower part of the monument.

- Bonnell children: Nicholas Bonnell, d.1688, and John Bonnell, d.1688/9,

infant sons of Captain John Bonnell and his wife Mary (see note of their monument below). A later member of the family,

Margaret Bonnell, d.1694, is also noted (picture above).

A great chest tomb with a high lid carved with foliage.

The panel on the side is somewhat forward, and the receding sides, as the curved ends of a tomb,

have large carved flowers, and some foliage upon them.

The remarkable monument to Mary Bonnell, d.1691.

- Mary (Morice) Bonnell, d.1691, with a Latin inscription, and added later,

d.1740, Captain John Bonnell, d.1702/3, Mariner. An exceptional monument.

The inscribed panel is styled as a hanging drape, subtly carved. The drape is held by

two thin nail supports, and the taut cloth between them at the top contrasts with the relaxed,

hanging folds to the sides and the customary fringe at the bottom. Tiny carved flowers

down the sides increase the sense of lightness and fragility. Above is a cartouche with

painted coat of arms, affixed to the oval backing panel on which the drape hangs.

At the base is a skull, facing forwards and again finely carved, with olive branches

wrapped around it in a grim wreath. Beneath the skull is a narrow support or shelf,

or perhaps it is the top of the construction below, which is a small panel with lower shelf

supporting crossed reedy branches placed straight against the wall, and with a carved ribbon tie

in the centre. Unusual. Oddest of all is the pair of large, twisted cartouches bearing the

coat of arms below, distorted fancifully as if some anamorphic painting.

The second wife of Captain John Bonnell, Margaretta, is noted below,

also James Beale Bonnell, and later members of the family, Jane and Mary Bonnell.

18th Century Monuments

- Anne Wainwright, d.1717, a column monument with a Corinthian capital on top:

the latter is considerably older than the monument. Pillar monuments are a notable but rather

rare type of monument at this time, but later on appeared in Victorian cemeteries

in much larger numbers than they had ever appeared in the churches.

Variety in 18th Century panels: William and Dorothy Nutt, Anne Wainwright, William Cooke and Thomas Clarke.

- William Nutt, d.1718, noting his family. As a short half pillar in pale marble,

with the inscription on the shaft, side pilasters in grey and white brecciated marble,

leafy capitals at the top. Above is a shelf, and on top, a slight dome with a cartouche bearing

a shield of arms, presumably once painted. On the left side of this as we look at the monument

is the surviving member of a pair of cherubs, seated upright, dabbing a cloth to his eye.

At the base, a further shelf, and below this an apron, curved forward to fit the pillar,

with curved brackets to the sides. On the front of this apron is a memento mori in the form

of a skull, facing to one side and well and grimly carved; beneath it is a corrugated cloth

or collar reminiscent of the bones of a spine, and there are butterfly wings to the sides:

a deaths-head it is not. Naturalistically carved leaves complete the ensemble, and the whole,

though appropriately grim, is well composed. The monument to his wife,

Dorothy Nutt, is noted below - pictures of both panels are above.

- William Walker, d.1720, Principal of Clifford s Inn, and with other offices.

An oval panel with sculptural decoration. There is a border of leafy branches with berries,

carefully carved and a most effective part of the composition. At the top, a shield of arms

in a leafy cartouche is flanked by two cherubs, meagre of body and plump of limb and face,

the one crying, the other with a missing arm that would have been flung melodramatically

across his breast. At the base, a support or corbel consisting of a central scrolled bracket

flanked by two winged cherub heads, rather grim of expression and quite characterful.

- Martha Bridges, d.1723, who died in childbirth, erected by her husband William Bridges.

An obelisk monument, a popular form where the backing panel rises to a broad version

of the Egyptian obelisk, serving in its shape as symbolism of death and rebirth.

The lower half consists of the inscribed panel, in white marble, with a border, and upper

and lower shelves of a grey and white streaky marble; the lower one protrudes somewhat suggesting

there were once sidepieces to make a complete frame. Above the upper shelf or frame,

just over half the total height of the monument, is the obelisk in black marble,

which has a widened base and rises with fairly sharply inclined sides to the bevelled point.

Upon the face of this is a shield of arms with a pair of small carved branches surrounding it.

Obelisk monuments: Martha Bridges, Daniel Finch, and James Bonnell.

- Mistress Anne Mores, d.1724, daughter of Sir William Rowe of Higham Hill, Knight.

Erected by her son Edward Mores, d.1740, Rector of Tunstal in Kent, and also commemorated.

Oval panel with narrow frame, a shield of arms in cartouche above, and a small shaped bracket below.

- Dorothy (Hawkins) Nutt, d.1725. Carved as a hanging drape, with central tie,

festoons of twisted cloth to two large knots at the side, then hanging freely at each side

of the inscription in the form of drop folds. Really rather finely planned and carved.

Unusual in that it has a backing panel, rectangular, and upper and lower shelves,

as more normally such hanging drape monuments of this period are free standing.

Above the upper shelf is a swan-necked pediment, with large carved flowers in the round ends,

and the open space of the pediment, which once would have contained probably a cartouche

or shield of arms, now holds only the base.

- John Braint, d.1728, erected by his wife Mary Braint, d.1729.

A fine Classical panel, with receding side pilasters, upper and lower shelf. At the top,

a small coat of arms, free-standing, and with a winged horse on it, and to the side,

a single shell-shaped lamp (the other is lost). There may once have been a broken pediment

containing the arms. At the base, a Baroque apron with jelly-mould terminus; smaller versions

of the same to the sides. The inscribed panel is in yellowed marble,

the surround in a streaky dark grey and white.

- Margaretta (Waterson) Bonnell, d.1736, daughter Sarah Bonnell, d.1766,

and son James Bonnell, d.1774, these latter two founding a charity school in West Ham.

An oval panel with a narrow rim. At the top is a painted coat of arms within a cartouche,

flanked by branches with flowers of various types, forming something of a frame

to the upper part of the monument. More interestingly, at the base is an extremely refined

line of three winged cherub heads, each looking in a different direction, and with considerable

grace (see picture below). Above them is a scroll, now blank but presumably at one time painted with some motto

or quotation.

Oval compositions: Walker, Margaretta Bonnell, and Bennett.

- Catherine Marshall, d.1737, infant daughter of Joshua Marshall,

Proprietor of this Chapel . Stained brown panel with curved top, and a white marble surround

with curly sidepieces and a shelf at the base. The Joshua Marshall named is not the

famous sculptor of this name, who was of the previous century.

- James Cunningham, d.1741, infant son of James and Martha (Rush) Cunningham, d.1754,

the latter of whom is also commemorated. White panel with curved side pieces,

receding, upper shelf and broken, curved pediment with the base of some lost ornament. Under the broad, lower shelf, is a blank, deep apron,

which likely also once had some carving upon it;

flattish supports to left and right, and a bobble hat corbel at the bottom.

- Thomas Clarke, d.1746, and offspring Edmund and

Elizabeth, with a Latin inscription. Above the panel

is a strangely shaped pot carved in high relief,

bearing a shield of arms on its body, and with the top and sides obscured by falling drapery:

this is extremely well composed and carved, with a great knot on top, which twists as it descends,

and with heaped up triangular folds where it lies on the shelf. At the base, a shell-like device

with a flame, and Acanthus leaves scrolling to left and right.

The backing is a brecciated greyish multi-hued stone, cut with a semicircle at the bottom

to mirror on larger scale the shelf of the main panel above. A good piece.

- Daniel Finch, d.1748, and brother William Finch, d.1758.

An obelisk monument, such as we saw in the Martha Bridges monument noted above.

The inscription is on the lower portion, beneath a decorated pediment with a shield of arms

contained within it, and with curly brackets to the sides, beneath which is a hanging set

of four small flowers in a miniature festoon. It leaves the monument looking curiously unfinished.

On top of the pediment, against the lower part of the obelisk, is a trophy cup in high relief,

with S-shaped handles and a striated body.

- Edmond Clarke, d.1725, and wife Elizabeth, d.1759,

erected after her death by a son, Thomas Clarke. White panel with upper shelf

almost certainly this was but the top of a full frame at one time and on top,

a cartouche with shield of arms, simply but elegantly carved with scrolling.

- James Collard, d.1791, and wife Elizabeth, d.1842. He was

Moneyer of the Royal Mint. Plain rectangular white plaque on a black backing,

with a small supporting block. Made by The Works, Westminster a fairly prolific maker

of generally dull panels.

- John Bennett, d.1791, and father James Bennett, d.1791, and the latter s wife

Elizabeth, d.1799. A cartouche monument, with a turtle-carapace shaped central field

and a surround of scrolls and leaves, with a small pot on the top carved in high relief.

Cartouches usually have thicker borders than this, but the carving is delicate and the

effect refined.

- William Cooke, d.1792, a shield-shaped plaque, slightly domed,

on a red and white stone backing, with a small upper shelf. Unusual.

19th Century Monuments

- James Beal Bonnell, d.1815, erected by his wife

Sophia Jane Maria Beal Bonnell, d.1841. An obelisk monument,

the lower part of which is cut as a casket end, with little lion s feet

underneath and standing on a shelf. The low casket lid is flanked with acroteria ( ears ),

and standing on it, on a series of steps, is a low relief carving of a pot,

decorated with bands of repeating floral designs and a festoon of flowers between the two handles

(one of which is missing), and the sigil BB in the centre. High above near the top of the obelisk

is a painted coat of arms. By Robert Cook, mason of London.

- Gulielmi [William] Sparrow, d.1816, with short Latin inscription, on a plain

off-white panel cut to form two small legs. On a black backing panel. Signed by Bainbridge,

who is obscure.

- Sarah Hibbert, d.1817, erected by her husband, John Hibbert, d.1849.

A white panel as a casket end, thus with outwardly angled side pieces of streaky marble,

and an upper shelf on which stands a wide pot or lantern, carved in high relief;

behind is a segment of a circle of dark marble - see picture below left. The base of the monument, which likely included

little feet, has been removed or is lost behind wood panelling.

19th Century white-on-black panels, horizontal designs.

- Sarah Deborah Holroyd, d.1823 with a poem. Panel with two broad side-pieces,

each with a recessed carving of a rather droopy flower (see picture at top of page), with equally droopy leaves

it is no accident, for the cut flower is another allegory for untimely death.

Shelf above and below, and above, a pot or urn with a stopper,

and lightly carved repeating decoration on the body and base.

To the sides of this at the ends of the shelf are short blocks with small roundels upon them,

and the black backing panel is shaped with concave sides and a bevelled top. Under the lower shelf

are small feet to the sides, and between, a crossed torch, downward pointing to

indicate extinguishment or death, and an upward slanting olive branch, perhaps for life in death.

The black backing here is curved. This competently carved monument is by

Matthew Wharton Johnson, a London mason - a picture is above, centre.

- Ann Corbett, d.1824, and numerous members of her family through to 1871.

Three panels, the two side ones acting as side pieces to the central one, with a dark,

narrow border, upper shelf, protruding at the two sides of this sort of triptych,

and two leafy corbels supporting underneath. As a monument, it is rather plain,

but as a family record, eminently practical given the amount of text.

- William Mathew Raikes, d.1824. A tall panel with a pediment shape on top,

but no entablature: Acroteria ( ears ) stick out to the sides of a strip of marble

with a stylised scallop shell between two scrolls, thickly carved, with the pediment

shape behind. There is a dropped centre to the base, and the dark backing panel is cut to shape.

Signed by R. Westmacott, South Audley Street, who is Sir Richard Westmacott RA,

most famous and prolific of this family of sculptors.

- Thomas Wilson Hetherington, d.1825. Oval panel with the top part and sides

bordered by crossed branches with delicately carved withering evergreen leaves upon them

it is rather unusual to have non-broad leaved branches. On a black backing panel.

The work of the mason-sculptor Joseph Theakston of Pimlico.

- Revd. Henry Barham, d.1827, with a poem. Panel with upper shelf,

on which rests a carving of an open book with a quote, and behind it, a crucifix and an olive branch;

a crown floats above. On a dark shaped backing panel. The base of the inscribed panel

is cut to admit a circular object underneath, but this has been lost:

maybe a carved wreath around a shield of arms. Signed by Bacon and Manning,

a partnership between John Bacon Junior,

illustrious sculptor son of a more illustrious father, and Samuel Manning,

a less well known artist credited with most of the later works

of this prolific manufactury.

- Agnes (Goss) Brown, d.1826 and offspring. Tablet with upper and lower shelf,

and cut to the shape of a pediment above, and a curved apron below, but no sculptural detail.

On a shaped black backing panel.

- Sophia Wilson, d.1832, and husband Thomas Wilson, d.1841.

With upper shelf above which is a roughly pedimental shape enclosing a small shield of arms

it looks as if there was a motto once and on top, a pot in relief with repeating patterns

round the body and stopper. At the base, a shape as if an upside down curved pediment

with acroteria, here doing duty as a nod to supporting brackets and a central apron.

On a black, rectangular backing. By M.W. Johnson, New Road, London, whose work we have met

already in the panel to Sarah Holroyd noted above.

W.G. Nicholl's panel to Elizabeth Morley.

- Elizabeth Morley, d.1837, erected by her son. Sort of an obelisk monument,

the breath at the top being considerable. The obelisk, if so we may call it,

bears a relief sculpture of the dying woman, reclined on her bed, head fallen back,

with a young girl of an angel in front of her, raising one hand in benediction,

the other hand holding the hem of her diaphanous robes. Above is a short inscription,

Well done, // though good and faithful servant. // Enter thou into the // joy of thy Lord.

the sort of wording which would not have been considered appropriate in earlier times

as it expresses a decision rather than a hope that the deceased would rise to heaven.

The fuller inscription is below on a panel with feet and a central wreath in low relief

with a rampant lion in a lozenge within it. On a grey backing panel. By the sculptor

W. G. Nicholl, a significant figure with several public works to his name,

including the lions and mermaids for St George s Hall, Liverpool (see this page),

and the standing figures on the Taylorian Institute in Oxford

(to the side of the Ashmolean Museum facing St Giles).

His monuments are few, and interesting.

- William Flamank Blicke, d.1838, staff surgeon in the British Army,

and wife Mary Lester Blicke, d.1866. Panel with upper shelf with above it a strip

of marble with the central part projecting forward and including two circles and a small shield

of arms, now blank, and scrolly carved surround as if a tiny pediment.

At the base is an apron carved an elegant scroll and with low relief carving upon it,

looking like penmanship rather than the idea of a mason-sculptor (a picture is further up, far right).

The signature of the mason on the black backing panel has been partially cut off:

.. own [Brown], of [Great Ru]ssell Street, [Lo]ndon. He was a rather prolific worker in stone,

and his monumental panels can be found in churches in London and the adjoining counties

more information on this page.

- Robert Matthews, d.1839, Master of the National School in the parish,

a plain streaky panel with triangular top.

- Jane Bonnell, d.1841, and Mary Anne Harvey Bonnell, d.1853,

with fine Victorian figure sculpture. The inscribed panel is bordered by two low relief pots,

tall and exotic, upper shelf and lower shelf with repeating pattern upon it.

Above, a panel bearing a relief sculpture of a girl (picture above), crouched in mourning against a funereal urn,

her head in her arms and resting on a swathe of drapery which coils round her legs

to become part of her Classical clothing; a nice way to bind the parts of the

composition together. To the sides are fluted pilasters which on a second look are seen

to be upturned torches, the snuffing out of life we have noted before, and above,

a pedimental block with curved top and lightly carved base. At the bottom of the monument,

two carved supports, and the shaped backing panel has a coat of arms surrounded by stylised

leaves. Graceful. The sculptor is J. Bedford of Oxford Street, London.

Like Brown of Great Russell Street, Bedford of Oxford Street was an industrious mason

with a large output of mostly simple works.

- William Greaves, d.1841, and wife Susanna, d.1833.

White panel cut with little feet and pointed top, on a shaped black backing panel.

- Alfred Thorp, d.1850, and wife Louisa Susannah (Plomer), d.1850,

just a couple of months after. A very good panel, sculpturally speaking,

with the central panel surrounded by ornament. To left and right are curly,

receding side-pieces with carved bunches of flowers of some variety,

in high relief with much undercutting. Above is an egg-shaped pot, decorated and covered

with a drape. At the base, a shelf with repeating Roman S-shaped patterns, and beneath,

a rounded apron with shell-like corrugation, and a shield of arms with delicate wavy

leaf surrounds, and a motto on a ribbon; at the base of this is a flower.

The whole is on a shaped black backing, itself with two leaf-carved supports.

- Rebekah Eleanora Weston, d.1851, cut to pediment shape above, with a

fine emblematic sculpture in high relief of a sickle cutting a blooming rose from the branch

the deceased was only 26 years old when she died at sea. At the base, a leafy central corbel.

Mid-19th Century panels: rectangular and oval compositions.

- Amelia Lancaster, d.1862, and Elizabeth Lancaster, d.1861,

respectively fifth and fourth daughters of William Norton Lancaster (unless Elizabeth

is the fourth daughter of Amelia; the wording is ambiguous).

An oval composition, with a white marble panel on a longer oval backing of grey marble,

with crossed vine branches forming a wreath over the top half of the inner panel.

The carving of the vine leaves, drooping as emblem of life cut short, is extremely fine.

- Sir William Domville, Baronet, d.1860, and wife Maria (Solly), d.1863.

Another oval panel, with narrow rim, with sculptural decoration in the form of crossed branches

of ivy, symbol of clinging memory, at the base and climbing up the sides, beautifully composed,

understated, and extremely Victorian: at the centre point above the stems is an oval with

the date 1863. At the top, a painted coat of arms with motto underneath and accoutrements above.

There is the usual black backing plate, but the shape of this is extremely unusual, intended,

I think, as a Gothic window with appurtenances but looking like a stylised rocket,

with fins at the bottom and point at the top. Signed by W.H. Burke & Co, Newman St, Oxford St.

- Sir James Vallentin, Knight, d.1870, blocky monument with upper shelf,

pediment shaped above, and resting on a lower shelf with feet, thus overall a tomb chest end.

On a black rectangular backing. Under it is a modern brass plaque, rather dark, to

Edwin Vallentin, d.1888, with the normal red capitals.

- Revd. Thomas Parry, d.1892, Vicar of Walthamstow for 41 years.

Panel with upper and lower shelf, and side pieces carved with flowers and leaves,

extremely delicately and naturalistically. At the top, an oddly-shaped pediment, rimless,

with a crown, stars and ring in a wreath of corn, with a ribbon, all carved in relief.

On a mottled and streaky grey marble backing. The basic elements of this type monument

are not so much changed from two or three generations earlier, but the whole is typically

late Victorian: the first word of the inscription with its engraved scrolling,

the naturalistic flowers filling the whole space to the sides, when previously

there would have been a stylised flower design on a flat pilaster,

the odd pediment were once there would have been a rimmed one with a central device,

and the shallow Gothic top to the backing panel rather than a severe Classicism.

20th Century Monuments

- Margaret Hicks, d.1901, plain streaky white marble plaque.

- William Houghton, d.1904, a monument styled as a pointed, crocketed blind window,

with small pillars at the sides and a deep base, on a Gothic window shaped backing.

It could have been Victorian, but the rich colours place it firmly at the turn of the

19th Century, when the use of coloured alabaster and marble returned in force after an absence

of nearly a hundred years. The thin pillars have ornamental tops, there are inset florets above

and below them, a line of low relief decoration at the base, and a general exuberance about

the monument. Signed prominently by the sculptor mason, T. Maynard of Walthamstow,

a local but not a familiar figure.

Return of the Gothic panel: William Houghton and William Shurmur.

Return of the Gothic panel: William Houghton and William Shurmur.

- William Shurmur, d.1910, Churchwarden etc. Another Gothic window monument,

of a style popular in mid-Victorian times half a century earlier. There are thin pillars

to the side, with red-brown marble shafts and leafy capitals, and a trefoil Gothic arch

above with leaves in the spandrels and on the edging. More leaves at the base.

The whole is on a shaped black backing.

- Harold Thomas Shurmur, d.1917, wounded at Passchendaele, died at Abbeville,

a bronzy panel with border of stylised leaves and crosses, most Arts and Crafts in design.

One of a series of World War I panels in the Church.

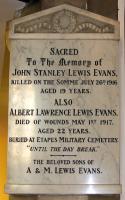

- John Stanley Lewis Evans, d.1916, killed in the Somme, and

Albert Lawrence Lewis Evans, d.1917, his brother. Panel of veined marble with pediment

above, bearing a wreath with a ribbon carved in low relief.

- Henry Reginald Pracy, d.1916, killed in the Somme.

Plain panel with ogee-shaped central appurtenance, in pale marble on a light grey backing panel.

- Lieut. Edward Benjamin Durnford Brunton, d.1916, killed near Beaumont Hamel.

Panel with thin pediment containing the IHS acronym above, and a scrolly base.

- Alfred James, d.1917, on HMHS Salta, mined in the Channel, a shaped panel.

- Sergeant Vincent Percy Bayne, d.1917 in action in France.

Plain panel with pointed top and a central corbel underneath, lightly carved with leaves.

- Sydney John Edwin Frederick Buchan, d.1918, killed in action at St Emilie,

white marble panel with carefully cut out shape but otherwise unornamented.

- Major Matthew W. Braithwaite, d.1918 at Colchester Military Hospital.

A pale panel with nipped corners on a black backing.

1st World War panels: Tattersall, Evans, H. Shurmur.

- Lieut. Percival John Tattersall, d.1918, tall panel with upper pediment with RAF

emblem carved in low relief. At the base, a support carved with scrolls and stylised leaves.

- Sydney Vincent Harris, d.1935, plain panel noting a commemorative window.

- William Mallinson, Baronet, d.1936, plain panel.

- Rt Hon Arthur George Bottomley, Baron Bottomley of Middlesbrough, d.1995,

and Bessie Ellen Bottomley, d.1998, plain panel with nipped corners on a black backing.

Ancient Brasses

- Guilielmus [William] Rowe, of Higham Hill, d.1596, a brass panel

with tightly packed Latin inscription, all in capitals, and no figure.

Mounted above it on a separate brass in the modern setting (of wood)

is a coloured painting of a shield at arms.

- Robert Rampston, d.1585. Panel with usual tight writing,

very difficult to read but recording a donation, no ornament.

- Georg Monox, Knyght, [Sir George Monoux], d.1543,

Somtym Lord Maior of London , and his wife Ann, d.1500, with two figure brasses,

four shields, and two ribbons in a modern setting. According to a label, the original tomb had

disappeared since 1807 . As noted above, Monox is important as one of the two benefactors of the Church.

The figures are kneeling, facing somewhat towards each other, and praying.

- Another pair of figures, this time standing, a man praying,

bearded and with a fine, thick mantle, and the lower portion of his wife s skirts

and feet; below it is an inscription to Thomas Hale d. 1588.

Other brasses

- Lieutenant Edwin Clark Vallentin, d.1867. Brass panel of the typical Victorian

revival style, with black spiky lettering, here in capitals, with the principal capitals in red,

and an inscribed line border. On a wooden plaque.

- John J Pearson, d.1926, panel cut to fit the spandrel

between two arches. He was choirmaster to the Church.

- A little dark panel beneath it remembers Peter Reginald Hatfull, d.1967, choirboy.

Also in the Church:

Angel corbel, Royal arms, Ambulance memorial.

Outside the Church

The Churchyard has an impressive collection of monuments, including a large number of

tomb chests, and the splendid casket tomb to Isaac Solly, d.1802, and his

wife, d.1819, and others of the family. The pinkish stone casket is raised up on a plinth,

and has lion heads with rings on each side, and stands on lion feet, and is decorated

with repeating wavy patterns. Among many good pieces we may note Mary Wigham, d.1777,

with a large festooned pot on top of the tomb chest, and Anne [Bainbrigge] Dobreis, d.1817,

again raised up, with dying birds in relief underneath poppy heads.

The lower tomb chest has a heavily carved coat of arms, and there are others

in the Churchyard with similar, and some other ornament look out for a book and chalice,

and even a serpent looped round to entwine with its own tail,

a symbol of rebirth much more common within a church than without.

Among the humbler headstones are various decorated pieces with relief carving

shields of arms, winged cherub heads and so forth.

St Mary Walthamstow Churchyard: tomb chests.

With many thanks to the Church authorities for kind permission to use pictures from inside the Church;

see the Church website at http://www.walthamstowchurch.org.uk/our-churches/st-marys/.

Top of page

Essex-in-London church monuments

Introduction to church monuments // Angel statues // Cherub sculpture

Nearby Leyton Parish Church (2 miles south) // or west to Tottenham War Memorial and thence north to Tottenham Parish Church // Monuments in some other London churches

Home

Visits to this page from 15 Nov. 2016: 9,556

Return of the Gothic panel: William Houghton and William Shurmur.

Return of the Gothic panel: William Houghton and William Shurmur.