Introduction to Smaller Church Monuments

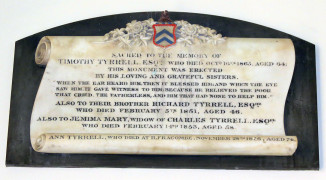

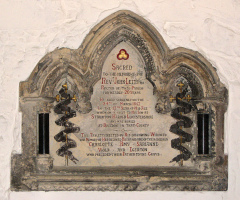

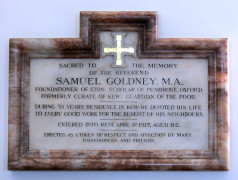

Typical church monuments, 16th-19th Centuries.

This page introduces smaller church monuments, illustrating the common types of wall panel. First a preamble on the older monuments, and our survey starts with the mid-16th Century Tudor kneeler monuments, and really takes off with 17th Century Classical panels, moving through the baroque and the colourful 18th Century, the simpler white-on-black 19th Century panels, and then a renewed burst of Arts and Crafts colour at the beginning of the 20th Century. Click on any picture to enlarge or hover for caption.

Preamble and beginnings of church monuments

For anyone who likes seeing sculpture, once familiar with the Victorian and Edwardian statues, and having visited the museums, the next steps need to be into the churches to see the monuments, taking us much further back in time and a different type of sculpture. It is hard to exaggerate the quantity, quality and interest of church monuments, and their significance in British sculpture. On the Continent, by and large monuments were excluded from the churches far earlier than in Britain, and there seems to have been some happy natural tendency of the Anglican church in particular towards having a variety of monuments on the walls. And unlike the museums which are generally found in larger towns, and the civic statues which also congregate there, churches are everywhere, and the most remote and rural parish church is as likely as not to have some sculptured monuments.

This page is primarily concerned with the smaller and more frequently found wall monuments from the 17th Century onwards, rather than the grand and ancient tombs of the great cathedrals. Further down this page are a goodly number of examples of these smaller wall monuments - around 50 in all. But let us start from the beginning.

Anything pre-Norman is extremely rare outside the museums - the occasional Roman carving dug up (and lots of Roman tile in the structures of certain churches), maybe the odd carved panel or fragmentary cross surviving from a Saxon church replaced by the Normans in the first few decades after 1066. Norman carving is widely if sparsely distributed, particularly around the doorways outside, and on capitals of pillars inside the churches, and lots of Norman fonts outlive the churches around them, but are less frequently carved. And surviving architectural carving becomes increasingly frequent as we move to early mediaeval times. But the earliest tombs with sculpture are vanishingly rare outside the Cathedrals.

Temple Church effigies, and 14th Century couple.

The church monument starts as a stone lid to a coffin, set into the floor of the church, which from very early times had incised lettering, and perhaps a crucifix or coat of arms. Early figure carvings are typically crudely cut, lying full length (recumbent), sometimes carved out of extremely hard stone, with a rounded head with the features lightly cut in rather than with the proper contours of a face with protruding nose and chin and so forth. The pose of the lying figure is usually rigid. The clothing or drapes are simple, without complicated folding, and there is no gravity - the lines of the drapery run horizontally along the lying figure as if a standing statue had been knocked over.

Later, the coffin lid itself, by now the base under the figure, had generally become a complete representation of a coffin in stone, thus a great plinth of box shape with carving on the sides, which is called an altar tomb if inside the Church, or a chest tomb or tomb chest if outside. (Here we say goodbye to the coffin lid, for this website does not concern itself with the floor slabs which continued into later centuries). If the coffin or chest tomb bearing the sculpted figure was set against a wall, there was opportunity for architectural features such as an arch above, as if of a small shrine, perhaps an entablature if of later date, and decoration such as heraldic shields could be placed above or behind (picture below right), or brasses, or little cherubic heads perhaps. A variety of powerful nobles, knights and clerics are found - rarer in the less grand churches, and with a few much celebrated, such as the figures in Temple Church, London (picture above left).

End 16th Century: early wall panel carving (hover for captions).

As fashions changed, sometimes a sculpture of a decaying mummified corpse would be placed underneath the recumbent figure, as a memento mori or reminder of death to the viewer. Gradually over time, the recumbent figures grew more delicate in carving, and ornate in their clothing, the effigies sat up or rolled over on their sides to depict living rather than deceased or at least sleeping figures. But the church monuments described on this page took off from the middle of the 16th Century. Firstly, wall panel monuments or plaques became fashionable (picture above left, click to enlarge). Secondly, these could be smaller and so less expensive and thus more people could afford them. And thirdly, there was an increasingly large pool of well off merchants, minor nobility and others who aspired to such monuments - the age of the wall monument had arrived.

Tudor and Elizabethan monuments

16th Century alabaster and strapwork.

The middle of the 16th Century takes us from the end of the Tudor period, with Henry VIII reigning until 1547, through to the Elizabethan period, with her long reign ending in 1603. Quite characteristic of this period are heavy wall monuments with a central panel and a wide border with relief carving. This is often in the form of what is known as strapwork - with an upper flat layer of stone cut away into straps and squares with cut out circles, scrolls and other devices above a lower layer of the same stone. Small inset panels or protruding bosses of different colours, borders, heraldic designs and some painting and gilding are characteristic of these monuments. They are often highly colourful, with a variety of alabasters and marbles in orange-and-cream, red with whte streaks, glossy black, serpentinite or other green marble, and various marbles with instead of a coloured streak, a 'broken lump' appearance, known as brecciated marbles. The sculptor-masons of the time had a good eye for design, and the rather solid pieces of carving, often without fine detail, fit well to materials where the different colours would make small detail difficult to appreciate, and are scaled well to the larger tombs. Often the best carving is on the shield at arms, which often consists of the heraldic shield of the deceased, surmounted by a knight's helm with much by way of falling feathers or plumage (the 'mantling' our heraldic friends would say), all in a circular frame with loops and scrolls on the outer rim.

From about the 1580s, a type of wall monument with figures became widespread, often loosely referred to as 'Tudor monuments' or, more reasonably, Elizabethan, or sometimes as 'kneeler monuments', which is the term I mostly use on this website. These monuments typically show a husband and wife, both kneeling on cushions, facing each other across a small prayer desk. They are generally under round-headed arches. Their children are usually ranked behind them - boys behind the husband, girls behind the wife, or underneath them in a separate panel, and are usually much smaller than the parents. Often they are painted, or in coloured alabaster with some highlights painted and gilded. Such kneeler monuments are among the most familiar of earlier church monuments, and are widespread through to the 1630s, then petering out. More on kneeler monuments on this page.

Turn of the 17th Century - Kneeler monuments.

The figures on these kneeler monuments wear contemporary clothes - armour or dark or red robes for the men, black or dark skirt and upper garment for the women; both generally wear conspicuous ruffs. The carving is skilled, with careful drapery, often extreme detail given to ruffs and ruffled hems, hair, and sometimes the contouring of face and hands. But some seem less well carved, or perhaps many layers of paint have filled in all the subtle detail and given a bland thick covering. Well or not well carved, little attempt at flattery is made, and the women particularly are often shown as rather old and rather plump.

Example of reclining Elizabethan figure, and kneeler facing forwards.

We do have some figures of the Elizabethan period which are similar in terms of physique and sculptural treatment and clothing and painting, but who are not kneelers. They may face the viewer as portrait busts, or lie or recline alone or in couples.

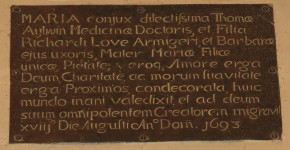

Tight lettering on an unornamented panel, late 17th Century.

At the much more humble end of the scale, spanning almost all of the 17th Century are plain monumental slabs of marble or stone with no border or carving, but simply inscribed lettering packed very close over the whole surface - often there is almost no margin at the edge of the slab. Some of these were once surrounded with rich borders, and the inscriptions are all that survive.

Now, returning the more richly-decorated monuments - strapwork and kneelers - these are classical monuments, with side pillars or pilasters (the shape of a pillar against the background wall), supporting shelves and friezes (entablatures) above, with on top of those, perhaps a pediment, but more usually a large coat of arms. At the base is a section that hangs down below the inscription and the lower shelf, called the apron. Because parts of the monument - shelves, bases of pillars - project forwards from the backing, there are supports - brackets, which themselves are often carved. From these Classical architectural elements, we can see the basis for the less grand wall monuments which followed.

17th and 18th Century Classical monuments

Baroque church monument of the 17th Century.

Here is one of these panel monuments, still grand enough, in St James Garlickhythe, to the memory of Seagrave Chamberlain, who died in 1675. It is of the era of Wren, and like a Wren church, it is baroque. The inscription is on a central rectangular panel. Around it are the classical elements of pilasters to the sides, pediment on the top, shelf as a base, and an apron below. But the side pilasters are curved and curly, hardly pilasters at all, decorated with carved leaves and flowers. The pediment is curved, and broken in the centre (although the terms are used fairly casually, strictly speaking a 'broken pediment' is broken at the top, as here, and an 'open pediment' is open at the bottom, so that its bottom shelf has the centre or all of it missing). On this example, the part below the lower shelf - the apron - has a carved cherub's head and festoons of flowers.

Example of the Classical monument: John Berry, d.1689.

At the more austerely Classical end of the scale is this one in the church of St Dunstan's Stepney, to John Berry, d.1689, so rather early for the type, with a central wigged bust of the deceased in front of a strictly Classical niche. The side pilasters are Doric, and the entablature above has recessed parts to the sides, termed 'receding' - receding pilasters become very common in such monuments. Above is a severe pediment, containing nothing - for excess decoration is here seen as frivolous. The bust stands on the top of a further curved pediment, with the inscription underneath, below a succession of layers each with 'head' and 'foot' in proportion. The only sculptural decoration other than the bust itself is the little bracket at the base below the shallow, curved apron, which is carved as what looks like a bunch of grapes enclosed by a leaf, and the shellike structures to left and right of the inscription.

18th Century monuments - tendency to the severely Classical.

We see both of these types - the more Baroque wall plaque and the more severely Classical one - throughout the 17th and 18th Centuries, with the Baroque dominating earlier, and being successfully less favoured as the decades go by. Above are some examples of the more strictly Classical tendency. The compositions are cleanly rectangular, with pilasters to the sides (including the far left one having receding pilasters), and upper and lower shelves, and nothing fanciful. The example with a figure is by Flaxman, a master of the cool, unexaggerated correct Classical. In this case, the pilasters are reduced to the sides of a rectangular frame. Above is a plain pediment. The other three cases have a flat top and a small Greek pot at the summit - in principle a funereal urn, but we shall stick to 'pot' The example second from left has a Classical apron below with rather more carving (click to enlarge and see it properly).

Below are examples of the more Baroque wall monuments. The side pilasters may be adorned as in the first case to the left, or entirely replaced with flowers and other ornament, as in the second example, which has carved rams' heads in place of the capitals (there is a page on this site about carved pillars). The rectangular field of the inscription may be encroached upon at the top, as in the leftmost and rightmost examples, or at the bottom, as in the second example. Baroque tops to such monuments include pediments which are broken (4th example) or curved (second example), or the pediment is replaced by some more curvaceous structure (first and third examples). Aprons below the lower shelf are carved into a range of curvy Baroque shapes.

17th and 18th Century Classical monuments - tendency to the Baroque.

There are other variants. Not particularly frequently we find an entire monument based upon a pillar, like as not with the inscription on the pillar itself. More frequent, but deriving from the Baroque, is the monument with instead of a pediment at the top, an obelisk. The obelisk recollects Ancient Egypt, long associated with the Necropolis and the reverence for death (see pictures lower down page). Though obelisks, usually as backings rather than free-standing elements of a monument, appear from the end of the 17th Century to the 19th Century, they areost frequently found in memorials of the latter half of the 18th Century (see this page for lots on obelisk monuments).

Church monuments based upon circular or oval compositions.

All the way back with the strapwork monuments, there was scope for circles as part of the design, and monuments based upon circular and later oval compositions also became most noticeable in the second part of the 18th Century, often very elegant, sometimes sparingly so with the absolute minimum of ornament, like some Robert Adam design, other times more decorated. They were never that common as a proportion of all memorials, but are widespread.

Cartouche monuments of the 18th Century.

A particularly elegant development of the oval is to make it slightly domed in the centre, and surround it with a delicately carved border of scrolls, Classical leaves of the variety called Acanthus, or hanging drapery, to make a cartouche monument. These have a tendancy to the Baroque, sometimes the very Baroque, and allows scope for the sculptor to demonstrate much ingenuity and virtuoso carving, including perhaps fruit, or winged cherubs among the foliage or drapery, or even whole figures. As well as Cartouches which form a whole monument, in miniature form, particularly in the earlier examples, they are often used to enclose the coat of arms of the deceased. They seem to appear as full sized monuments from the early 1600s, with their peak in the later 17th and earlier 18th Centuries, though again, never common, as there was so much work for the sculptor. Having a natural curve, they were sometimes favoured for monuments to be attached to pillars in churches, between nave and aisles. Definitely to look out for.

Hanging drape wall monuments.

And another type - the wall monument carved to look like a hanging drape. This would be like a small sheet, tied at the top two corners so that there would be a gently curving fold between them, drop-folds to the sides, which would act in place of the side pilasters in the monument, and in between a flat surface on which to cut the inscription. Typically, the base of this sheet would be another curve, and the edging would be fringed, and typically gilded (though a lot of gilding is modern and may not have been part of the original design). The elegance of the drop folds, the delicacy of the fringing, the complexity of the knots and the cords which were often carved to tie them, were all opportunities for the sculptor to demonstrate his invention and skill. At the top, there could be a backing, a place for a shield of arms, or some carved cherub's head or other decoration. This style seems to have always been quite unusual, but is perhaps most often found in the first few decades of the 18th Century, though examples are occasionally found from much later.

18th Century putti in church monuments.

Without wanting to diverge to those monuments which have full figure sculpture, we have already noted that many monuments have winged cherub heads included in them (there is a separate page on architectural cherubs on this site), and full figure cherubs and putti are common in the 18th Century. I am not particularly a fan of the breed in general, but it must be admitted they are of long pedigree within sculpture, particularly during the Renaissance, and many of these later English cherubs hearken back to that style. A pair of such cherubs at the sides or on top of a monument can do for figure sculpture when an allegorical figure would be too tall and slim for the composition. The pictures above show free-standing ones, and include a mourner holding a skull, a rather jolly one holding a knight's helm, one with an upturned torch, symbolising the snuffing out of the flame of Life, and a snivelling one with a crown.

Winged cherub heads: single, pair and triplet.

We have already seen some winged cherub heads in the examples so far; the couple of pictures above exemplify the grouping of cherubic heads into pairs and triplets - see a variety of other such things on this page.

'Also on the Monument' - accoutrements

Accoutrements (hover over for captions).

Perhaps here, between the 18th Century and the 19th Century, I should divert and say something about the additions - accoutrements if you will - emblematic of death and rebirth which were charactistic of the 17th and especially the 18th Centuries. The skull was always popular as a reminder of death (memento mori) and that the most noble and proud person would come to dust. Often the skull would have no lower jaw, particularly if free standing rather than carved in relief. Sometimes there would be crossbones under the skull. The counterpart of the winged cherubic head, indicative of going to heaven, was the Deathshead, a grinning skull with bat wings. Lots more about skulls on this page. From early in the 18th Century, and much more as time went on, small funereal urns make an appearance, typically in high relief on a backing or simply against the wall, or on the larger monuments, free standing ones. These might be draped, either symmetrically, or with the drapery in front on one side of a classical pot, and behind on the other, and often falling asymmetrically far down one side of the monument, as in Death veiling Life. Instead of urns, there may be lamps, of Roman or Aladdin style, often with carved flames, indicative of the flame of eternal Life, or Faith. The use of the Egyptian-style obelisk as a symbol of death and reincarnation has already been mentioned (and see this page).

Obelisk monuments, recalling the Ancient Egyption preoccupation with mortality.

Crossed branches also appear in this period, though much more commonly in the 19th Century, which may be visibly broken, as in plucked from their family tree and thus to die, or indicative of peace. Carved sunbursts near the top of the monument indicate Heaven. Winged cherubic heads also indicate Heaven, but cherubs and putti may also be mourners, weeping with handkerchiefs to their eyes or gesturing melodramatically, popular in the mid and later 18th Century. Drapery itself indicates repose, collapse into stillness, or simply recalls the funeral pall. Larger monuments may have drapes near the top and sides as if pulled aside from some pavilion erected above the deceased so that mourners can glance within. Wreaths are common marks of respect for the dead, and there are many on church monuments from the later 18th Century and onwards, and cut flowers of various types recall the fragility and short span of Life. The occasional broken pillar generally indicates the extinction of the male line of some noble family, and this type of monument became popular out of doors in the churchyard or cemetery - see the page on Introduction to Churchyard monuments.

Wilting plants as symbols of mortality.

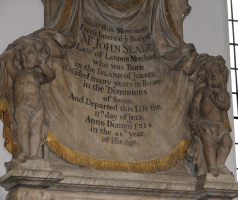

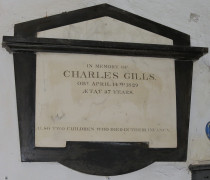

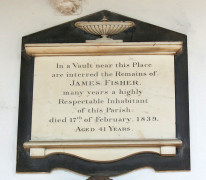

19th Century panel monuments

By around 1800, with the Napoleonic wars, the supply of much foreign coloured marble was cut, and there was a change to overwhelmingly white-on-black monuments (see this page for lots about them). But this predominance of the monochrome continued through the 19th Century, even when trade with the Continent became free-flowing again. Many churches are dominated by small black and white wall monuments from the 1800s-1840s. From this period, there are many very simple monuments with white marble in front of a rectangular or cut-to-simple-shape black marble backing. Some are simply two cut panels, or one white panel inset into a larger black one, and belong entirely to the mason's craft rather than the sculptor's art. Many of these are monuments for the burgeoning well to do middle classes, where the expense of serious sculptural treatments would have been prohibitive. However, often there is a compromise, with a bit of sculptural adornment.

Black and white tomb-chest end or casket end designs, 1810s, 20s, 30s, 40s and 50s.

One of the most common designs hearkens back to a much earlier type of free-standing monument, the tomb chest. These came in two varieties - a great outer coffin in stone on four short legs at the corners and with a lid above a lip, and caskets, similarly with short legs, but where the sides were angled outwards as they rose, and on top would be a lid which was raised in the centre like a shallow roof. The new wall plaques then, look like one of these tomb chests or caskets seen end-on. They actually began to appear in about the 1780s, but really took off around 1810, and thereafter were a staple of the monumental mason's oeuvre. The inscription could be cut on the centre, the little legs could be carved if desired, and at the edges of the side seen by the viewer, pilasters (remember, those flattened pillars) could be added - though in a casket design, these would be angled outwards rather than vertical. The angled lid looked rather like a pediment, and by putting a shelf below it rather than a line for the lip, a pediment space was created which could hold some small carved shield or wreath. To the sides of this lid or pediment, it was common to put small carved 'ears' called acroteria, often carved with a striated simplified anemone flower pattern (anthemion). Many variations of these tomb chest ends and casket end monuments are found - the set above, one from each decade from the 1810s to the 1850s, are all from St John Maddermarket in Norwich.

We should also mention the sculptors themselves, such as we know them, though that is not the focus of this page. Medieval sculptors are overwhelmingly self-effacing, and all the way through to the end of the 17th Century, it is very rare that the sculptor of any particular church monument is known outside of those in the great Cathedrals - and where they are known, it will usually be from records of who was paid for the work rather than any signature, except in rather rare cases. The 18th Century was the first time that it became common to sign sculptured monuments, and it is from about 1740 that we first find it fairly common to see signatures carved on the monuments, sometimes discretely, in other cases with almost as much prominence as the name of the deceased.

Variants on tomb chest and casket (hover for captions).

Even on the most simple wall monuments, from the 1780s onwards into the 19th Century, many masons and sculptors sign their names, and it is always worth a look to see if you can see the signature on a monument from this later period. Among the mason sculptors, there were a few whose work is found all over the country, such as the firm of Gaffin of Regent Street, and many whose signed work is found only in a few churches in some very local area, for example Woodiss of Sheen in South London.

Lots of monumental sculptors and masons are covered on this website, with brief notes on their biographies, style and works, accessible from individual church pages where their pieces are, or via the index of sculptors.

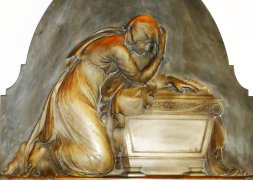

Monumental sculpture of girls with pots, 1800s-1840s.

For more ostentatious monuments, the inventive 19th Century mind meant that endless possibilities opened up for sculptural adornment. The sculptured plaque or frieze makes a strong reappearance, with scenes from the deceased's life, or deathbed scenes (see picture at bottom of this page), often rather cool and severe in their Classicism. From the later 18th Century and with more in the first part of the 19th Century, we see the classical girl mourning against a pot, a thoroughly commendable development. There are many excellent examples, as full figures, or as high relief, and these are surely among the most enjoyable church monuments to discover. Typically we might have a central pot, or casket, with a girl standing leaning against it, or seated against it, or even hugging it. In some cases the figure is clearly allegorical, in others she may be taken as the mourning wife. We may have two figures, or one might be mortal, the other an angel - an interesting combination of the Christian symbology with the essentially Pagan Classical. There was also a vogue to include a carved portrait of the deceased, often on a roundel on the base of the pot or side of the casket, but sometimes as a plate carried or held by the girl or an angel. The figures may be severely Classical Hellenic, shown in calm repose with faces often in absolute profile, or Hellenistic and Baroque, with twisting bodies and swirling drapery, so that the once flat wall plaque becomes an extremely three dimensional work which can be appreciated from a range of different views. Some very notable sculptors specialised in church monuments of this type, such as John Bacon and the junior Westmacott. There is a page on this site all about Classical girls on monuments.

The monument as a scroll, landscape and portrait format.

Some of the monument types have disappeared by this time (dawn of the 19th Century), such as cartouches, but even at the simplest level there are new variants on the wall panel monument. Aside from the tomb chest ends and casket ends mentioned above, there are monuments carved as unrolling scrolls, the 19th Century equivalent of the hanging drapes of the 18th Century, and something not really seen in church monuments since late medieval times - the return of the Gothic. This would be typically as a Gothic window style monument, with one or three lights but the stone inscription where the glass should be (so termed 'blind window'). Often these monuments incorporate side pillars in a different coloured stone or marble. Although this website is not particularly concerned with brasses, we should note that from mid-Victorian times, there is the renaissance of brass memorials, as typically rectangular or Gothic arch panels, with lettering, often highly Gothic, in black (often the hard-to-read spiky blackletter) and with initial capitals and important names in red; more an exercise in calligraphy than sculptural.

Return of the Gothic panel, mid-19th Century.

The end of the 19th Century brought something else back which had mostly disappeared since the 18th Century - the widespread use of coloured marbles and alabaster. Art nouveau and Arts and Crafts memorials appear in the 1890s through to the late 1900s, with a brief revival after World War 1, with rather more of combinations of the coloured stone and gilding than much carving per se. The large number of memorials to garrisons and groups of soldiers who perished in WW1 include some with cast bronze designs, of wreaths, small figures of Britannia and Peace, and Garrison coats of arms.

Early 20th Century and the revival of the coloured monument.

And then, with the last of these war memorial slabs, sculpted church monuments come to an abrupt stop. Later monuments are far fewer, often confined to vicars and other ecclesiastics of the church, and typically extremely plain, as if to have ornament or excess expense on such things was felt to be inappropriate or embarrassing. There are of course a few exceptions, but in general, by 1930, we have to mourn the demise of the church monument itself.

To end more brightly, there are tens of thousands of panel monuments which survive for us to see, across many thousands of churches across the whole of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland (with the custom and in later times often the monuments themselves exported to America, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and many other places). The pictures on this page are from various churches in London and elsewhere, and many thanks to all the churches for being or arranging to be open to visit and photograph. This website includes individual pages on the monuments in about 170 or so of these churches, mostly in London (both the City of London churches and more widely), the home counties and some of the great northern cities - I hope you find them as interesting as I do, and will be lured into these and other churches to explore and see more.

Bob Speel.

Churchyard and cemetery monuments

Kneeler monuments // White-on-black monuments // Classical girls on monuments // Cherubs // Winged cherub heads