This page looks at sculptures showing beauty, here taken as the beauty of the female form, with mostly Victorian, Edwardian and Art Deco statues. Of course each person will have their own idea of feminine beauty in sculpture, as in the other arts, but I think it is possible to at least point to several frequent types, which hopefully will appeal to anyone chancing to visit this page.

The beauty we notice first is generally the face, so this is where we start. The Classical beauty of ancient Greece has as the main characteristics of the face the nose, which is almost parallel to and almost a continuation of the fairly broad forehead, the lips, particularly full in the lower one and undimpled, the cheeks, which are rounded, as is the chin, with a fullness underneath, and of course the eyes, which are large and almond shaped. In a Classical statue, there is generally no expression, or at most a solemnity. Especially from the 18th Century, there was a fashion in figure sculpture after the ancient Greek fashion in Britain - John Flaxman was faithful to this style in the 1800s, and it persisted to some extent through the Victorian era. Although it is the face which we are looking at, these examples include the figure too, to make the point about the Classical robes such statues wear.

Beauty of the Classical face in sculpture.

While many Victorian statues are Classical, many are simply Victorian. Our Victorian beauty comes in several variations. There is the plump-cheeked, small mouthed girl with big, wide eyes, the soft-faced girl with Victorian determination and slightly pursed lips, and varieties of feminine chaste innocence. She may have a modern or ancient hairstyle, ancient, exotic, or 19th Century clothing or none at all, but generally an ideal proportion and beauty of face and form.

And then we have the more Pre-Raphaelite type, in the spirit of Rossetti, with her long hair, large and expressive eyes, often with heavy or heavily delineated eyelids, and full mouth. She has strong features with high cheekbones and a firm chin. The examples below could have stepped from the paintings of Rossetti, Millais, Holman Hunt, Sandys or Poynter - especially those towards the right, and she on the far left reminds me of paintings by William Dyce. Next to her, the nude second left combines a Pre-Raphaelite style face with the un-Pre-Raph body of an athlete, while the sylphlike winged statue of a girl in the centre is a softer creature altogether.

Pre-Raphaelite girls in sculpture.

But back to our beautiful faces. We can also find something in between Classical and Victorian beauty, with the nose descending from the forehead in Ancient Greek style, but the eyes and mouth and chin of a Victorian girl. There is a heroicism to these regular-featured girls which suggests one way in which the Victorian artists saw their muses as descendants of Ancient Greece without feeling the remoteness of ancient statues. Looking at this group, we could be tempted to see them as more Classical than they are, until we compare them to the purer examples near the top of this page.

Rather earlier than Victorian is a type of beauty originating in the 18th Century, with a particular roundness to the face, combined with a softness of both face and body, without much if any visible musculature. Like the Victorian round-faced variant, the mouth is not large, the chin small indeed, but the nose has a certain length, and the eyes are more lidded, and typically with rounded eyebrows. The two below epitomise the type as found in many church memorials of the period.

Towards the later Victorian times and into the Edwardian era we have the New Sculpture, with a new type of beauty. We see faces with more of a bone structure, particularly to the cheeks and around the eyes, which are often half closed, secretive rather than demure. There is often an expressiveness to the mouth, a half-smiling appearance. Their hair is often short, leaving the whole neck exposed, and often these girls are of a slenderness unusual in the typically Victorian beauty, or the muscular Classical beauty. In some ways, they are perhaps closer to a modern ideal of femininity.

New Sculpture of the 1900s: the feminine ideal.

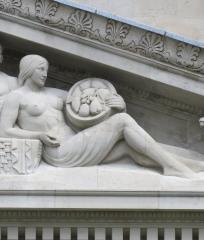

Let us go on then to the typical Edwardian beauty. She too generally has shorter hair, or hair piled up to show her neck. It covers much of her forehead, which in any case is not so broad as her Victorian predecessors' foreheads. Our Edwardian beauty has a face with typically rounded cheeks, healthy rather than slender, while the chin may be fairly broad, and the mouth too. That mouth and the eyes show that the Edwardian beauty is generally quite pleased with herself, with a look of satisfaction bordering on a slight smile. Edwardian times saw many grand buildings with much sculptural adornment, and I have chosen the examples below to be predominantly architectural sculpture.

A contrasting look to the face, deriving its beauty by virtue of its winsomeness and fragility, is the rather thin face, with a hollowness to the cheek, an anxiousness to the gaze, as in these examples. As can be seen from the two figure statues flanking the keystone head, there seemed to be no need to combine the slender face with a fragility of limbs or body.

A variation of the beautiful sculptured face, not associated with any specific date, is where the appeal comes from the directness of the gaze, often combined with the technique by which the eye is hollowed out, so that the shadow gives the appearance of the black pupil. What a difference from the demure, downward gaze from half-lidded eyes of some of the examples we have seen above. The two girls to the far left are really quite high up on the buildings they adorn, yet those eyes stand out from far below.The keystone head, fourth along, is an example of the direct gaze without the hollowed out pupil, and may be contrasted with she immediately to the left.

Finally before we leave the beautiful face, we ought to mention those statues where the hair is given the emphasis and arrests our gaze. Such faces are most usually from Victorian times – think of those Pre-Raphaelites again – but Edwardian and later examples are also found, as in the early 20th Century example below far right, who wears Arthurian clothing and has beautiful Arts and Crafts hair (you'll need to click to enlarge to appreciate it properly). Next to her, the seated nude has what we might call Symbolist hair - were she to stand up, it would hang almost to her ankles.

The hair as a feature in sculpture.

The perfect, symmetrical face framed by exotic hair is a not unusual theme for Keystone heads, of which a few examples are shown here - more examples are on this page). The foliage and flowers in the hair is sometimes allegorical, sometimes purely decorative.

Female keystone heads emphasising the hair.

Enough, I think, of beautiful female faces per se. The female nude is more central to sculpture than to painting, and the ideal feminine form has been a preoccupation of sculptors throughout the ages. The Classical type of nude is found frequently in Victorian and Edwardian times, and here are typical examples: we see long-limbed figures, with visible musculature, emphasised or under-emphasised, a look of the athlete, and above all a look of firmness to the body, the breasts, the thigh, the columnar neck and the strong shoulders.

Our non-Classical Victorian nude has a different ideal. She has a fuller figure, with rounded breasts, a curve to the stomach, a waist that is not narrow, but wide hips so that there is an overall feminine curviness to the body, and a feeling of gravity throughout, especially to the thigh and lower leg, and in the feeling sometimes of weight rather than muscle to the arms. The central figure below is an engraving of John Gibson's famous Tinted Venus, which caused a scandal by appearing 'too nude' by virtue of the colouring, and contemporary rather than the more Classical figure we might expect from the title.

But like the faces which are part-Classical, part-Victorian, so too we see plenty of examples of statues with bodies which have the Victorian measurements, but a little more muscle at least to the arm, perhaps a firmer rather than femininely curved stomach, a sense of vigour rather than inactivity. The examples below include free-standing statues, architectural sculpture and high relief. The engraving second from right is particularly interesting - we see a romanticised figure, perhaps more romantic in the engraving than in the original, and yet this is combined with the muscular arms and the hard, well-muscled stomach.

Between Classical and Victorian.

We can take our classification too far, and it is important to remind ourselves that each statue is the individual work of an individual sculptor rather than necessarily fitting neatly into a style. This seems very much the case for the nude statue of Edwardian times, who is often more recognisable as such by her face than her body. Thus we see Victorian body types with their feminine curves and somewhat more muscular girls tending to the Classical in various degrees. By way of exemplifying this, look along the line of figures below just at the breadth across the hips.

Edwardian nudes: variety of form.

We also see a greater variety of poses, for example as below. The girl to the second right, though in England is not English sculpture, and is from group by Oscar Spalmach in the garden of York House, Twickenham, and she below left is Gilbert Ledward’s Awakening, to be found on Chelsea Embankment.

And the swirling hair of the York House girls reminds us that the turn of the 19th Century also brought Art Nouveau, with its naturalistic forms and figure sculpture adapted to the purely decorative. Here are three examples: the first is a caryatid, in place of a pillar (lots more examples on this page).; the centremost is stretched out above a curved pediment, twisting her supple body almost a quarter to the left compared with her legs and head; on the right is the torso of one of Alfred Drury’s lampstands in Leeds City Square, beautiful indeed - more on these sculptures on this page.

After this eclectic variety of the feminine ideal in sculpture in the 1900s, the outbreak of the First World War brought a reaction against decoration and ornament, with the last of the Edwardian style of beauty appearing in some of the allegorical figures on War Memorials. After that, a pause before the Art Deco ideal female figure appeared, reaching a peak in the mid-1930s. We must remember that many of the Art Deco sculptors were trained by Victorians in Edwardian times, and so we must expect a gradual change from the ideal Victorian and Edwardian statues through to the Deco, with no clear break. Below left, two war memorial nude figures, small-breasted but certainly not yet Deco. Then a spandrel girl on a Classical building, an athletic nude not at all of the Greek type, and pointing to the future. Then successively more stylised and vigorous girls until we reach the new beauty of true Art Deco sculpture. Look at the last two examples - hard and muscular again, hearkening back to the ancient Greek, yet this time more the stylised ancient Greek girl found on red and black figure vases rather than those of sculpture. In the final figure, the breadth of her shoulders, the depth and capacity of her chest, and the heavily delineated muscles of her legs are more the Spartan warrior than the maiden, and yet through the softness of the features of her face and her small breasts, the composition of her pose, and the graceful repeating folds of her drapery, we have another image of feminine beauty.

Nude figure sculpture from Edwardian through to Art Deco statues.

Before leaving the nude female figure for the time being, here are three more modernist statues, each with a different way of capturing of feminine beauty - an outdoor statue, a studio piece, and an architectural statue.

A completely different type of beauty in the feminine figure comes through what we might describe as harmony: the flow of drapery around the female body, with repeating folds, gracefully arranged, the outlining of the feminine form beneath contrasted with the heavier drapes across the lines of the figure, and the harmony of the composition of the figure.

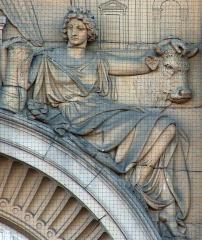

Architectural figures first. Our first example, below left, is a niche statue with such graceful drapes; she is an allegorical figure of Music, and her relaxed pose and the repetitive concertina folds over her lower body and legs suggest a quiet and melodious tune. Then a girl in medieval dress with the tools of Industry, carved in high relief; again, it is the folds of her long dress which makes the composition, though here the pose is more active. Such figures representative of Industry are widespread - see this page for some others. Next, a semi-nude cowled figure forming a summit to the Palace Theatre on Charing Cross Road (see this page); the single sweep of the garment diagonally across the breast and then downwards makes this figure. To the right, another spandrel figure, with gracefully ovoid lines of drapery across her upper body, contrasted with the more angular folds across the legs.a calmer, seated figure with a cow – her face is perfect and ideal, but it is the heavily undercut drapes which catch the eye. The long, diagonal lines of the figure are contrasted in the composition with the flat, horizontal line behind her arm and to the head of the cow.

Beauty of the harmonious female figure.

Free-standing statues now, fair enough of face, but in my opinion, again with their beauty deriving as much from their drapery . First a Victorian type, with her statuesque figure emphasised by the tightly wound drapery across her breasts and the heavy fabric knotted below her stomach, serving to outline her torso and add to the width of her hips. Then an Edwardian girl, with long skirts almost transparent across her legs, and with a swirl of heavier material behind her shoulders, a beautiful composition. Then the once-famous girl with a pitcher in Berkeley Square (see this page), all harmonious V-shaped folds across hip and thigh and leg. Then the angel of the Boer War Memorial in Cardiff, one of the most beautiful examples of symmetrical, light drapery to outline the feminine form. Another lightly-draped statue of a girl with a pitcher, with U-shaped curves emphasising repose as well as echoing the curves of the feminine form. By contrast, to the far right we have a heavily draped figure of Agriculture, where the drapery is heavy enough to make a form and feature of itself (more figures of Agriculture on this page), and then Thornycroft’s figure of Artemis, the swirl of her light, short tunic bringing a sense of captured movement to the figure.

Freestanding harmonious female figure.

We have not really said much about harmonious pairings of figures, but they can epitomise the beauty of harmonious composition. Here we have examples of standing, seated and paired standing and seated figures: they are bound together by overlapping, by their glances, by the flow of drapery and angle of arm from one figure to the other.

With groups of figures, the beauty of harmony can be taken to emphasise repetition in the figures, combined with enough variation to provide interest to the eye. Below left is John Henning Junior's figures after the Parthenon Frieze, on the Hyde Park Screen in London, a most perfect composition. Then four lively 1930s girls in relief, with a beautiful compositional line along arms and shoulders, and a line of parallel legs below. Next, a graceful, harmonious grouping of three female figures pouring water, and a panel from St George's Hall, Liverpool, a Symbolist work in low relief showing several nudes, cleverly balanced, and and a line of terra cotta girls forming a processional.

A special place must be reserved for the beautiful statues of girls and descending angels in funerary settings. Our first example is utterly Classical, whose beauty comes from the simplicity and purity of composition, mirroring that of the girl herself - this is one of the works by Flaxman noted earlier. Next, a figure of Justice, a tragic beauty, her weight on her right leg as we look at her, emphasised by the diagonal hem of the thin upper garment, and a second Justice figure in more complex drapes (other figures of Justice are on this page). The other figures below show different drapery styles. More specifically on mourning figures further down this page.

Female figure in monumental sculpture - inside.

Out of doors now, and here are a group of angels and feminine figures from the graveyard and cemetery. Variety of Classical drapery is best studied there, and these beautiful figures are satisfying to the eye from any vantage. Tall or sweeping wings offer further opportunity to the sculptor for the composition - more such creatures on the angels page.

Feminine figures in the graveyard and cemetery.

As before, figure groups allow for further compositional variety. Below left, the two figures are on opposite sides of the funereal urn, but are tightly bound together by the flowing lines of the drapes, among the most perfect we can find (the monument is in the New Church at Marylebone. Next, one of the groups on the grand Earl of Sheburne monument at High Wycombe, by Scheemakers - see this page. Next, a little churchyard monument with two distantly placed kneeling angels brought together by their gaze upon one another, and then to the far right, two repeating figures of angels.

Harmonious sculptural figure groupings.

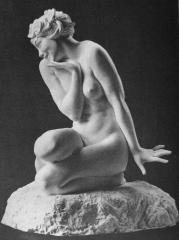

From the generality of funerary figures, to the empathy of pensive and sad female figures. Nudes first, mostly studio pieces, with a winsomeness appealing equally to the Victorian and Edwardian sculptor. The two to the far right are in the pensive category, in the 'bather alarmed' genre.

Ideal figure sculpture showing beauty of sadness.

Inside the churches, female mourners are a staple of feminine beauty, the common traits being the downcast gaze from the tilted head and the leaning on the elbow, giving ample opportunity to show the elegant profile or three-quarters view, the feminine curve of neck and shoulder, and of course the lines of the drapery over the female figure. Oddly, by the 1800s it is often highly unclear if these feminine figures are allegorical or intended to be the surviving spouses of lost husbands. Regardless, surely such figures form one of the least well known yet most prolific and skillfully formed groups of sculpture in Britain, and a paean to beauty.

Mourning girls inside the church.

Out in the Churchyard and cemetery our female mourning figures may be found in their multitudes, often rather repetitive in pose, but with many excellent examples of the beautiful figure. In addition to the bent head and the head on the hand, we see many more cases of hands either clasped together - something that went out of fashion by the 1650s inside the churches, never to return - and embracing of crucifixes rather than the pots found indoors. Alas, we may mourn too, for these outdoor figures, which appeared rather later on than those inside the churches, will last less long, as ivy and atmosphere on the soft stone crumble and erode them away.

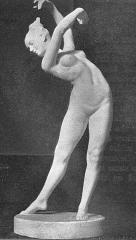

Another type of beauty is the beauty of the pose of the figure, the twist of a supple body, the expressiveness of a hand, the stretch of a fair arm. We have seen some examples above, but undoubtedly this type of beauty lends itself best to the nude figure. The girls below show the variety, and we may note that the sense of movement means such figures are far more common later in our period, with less opportunity in the Classical figure, where stillness or calmness of pose tends to be the rule,

Ideal female figures with beauty of pose.

All those above are studio pieces, so here are a few outdoor figures, freestanding and architectural sculpture. The two girls to the right show how close the Caryatid figure pose can come to a stretching pose.

If there is one type of beauty in the active pose, then there is surely another in the passive one, the reclining or completely relaxed female figure, featuring in several statues, particularly, and unsurprisingly, of the Art Nouveau period. We see here seated, lying, and even languorously standing girls.

Ideal figures in relaxed pose.

I half hesitate to advance the idea, but I feel we must acknowledge there is a beauty of sweetness too. There are so many Victorian statues, particularly angels in churchyards and cemeteries, which are too sweet, cloyingly so, as there are in paintings too, but there are some which manage to convey sentiment without sentimentality, and retain a beauty arising from but not spoilt by sugariness. I particularly like the contemporary engravings of such statues, and include examples here. The most usual type are seated girls, who in their downward cast gazes and protective gestures suggest modesty, chasteness and purity. There is usually some bit of drapery, but regardless of the state of undress, their hair is always immaculately groomed.

Although statues of beautiful sweet girls are often sitting, we can of course find standing poses and stepping ones, such as below, with the inclusion of a well-known flying one exhibited at the 1851 Great Exhibition.

And here are some architectural ones, also with sweetness of face:

As said already, the funereal statues tend to veer too strongly to the sentimental, too much so for our taste today, but here are a couple which I fancy stay on the right side of the line, all of the pure child type, generally representing the death of a child, though in almost all cases being an allegorical representation rather than attempting a portrait.

As an antidote to sweet beauty, something more exciting is what we may term the exotic beauty. Though there are Edwardian and later examples of such statues, this type is above all the preserve of the Victorian sculptors, who were obviously delighted and interested in foreign and exotic beauties, giving them headdresses and palm leaves and gaudy necklaces. With that goes a sense of savagery, so that in these statues we generally see a hardness and distance of expression rather than a more demure one.

Before ending this page, I wanted to include at least a few examples of more modern sculpture of beauty. Here are some beautiful girls from the Art Deco period all the way through to the new millennium, showing that despite the interest in abstract sculpture and the move to other art forms, including the near-abandonment of the decorated building, there is still a continuation of production of feminine beauty in sculpture for us to enjoy:

And thus ends this page. There are plenty of other examples of beauty in sculpture distributed on this website, particularly on the sculptor pages (link here) and the Allegorical Alphabet pages (link from here).

Visits to this page from 12 Aug 2016: 10,075