The statues around St George’s Hall fall broadly into two groups: those on the steps to the eastern side, that is to say the Lime Street Station side, together with those to the north; and those to the Western side in St John’s Gardens. This page deals with the first group. The picture above shows St George's Hall as seen on the approach into town from Lime Street Station, with the eastern side to the right; if you click to enlarge, you can see the General Earle statue in the advantageous corner position.

We need to walk around a bit to see the statues, as they do not naturally fall in a sequence from one end of the Steps to the other. We must start, of course, with Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

Two aspects of Queen Victoria statue by Thomas Thornycroft.

Two aspects of Queen Victoria statue by Thomas Thornycroft.

Queen Victoria reigned for over 50 years and the larger number of statues of her date from later in her life or are posthumous, so we are most familiar with the older Victoria, with her serious face, heavily lidded eyes, characteristic lines between mouth and cheeks, and rather solid figure, either seated on a throne or standing in voluminous robes. Here however we have a young Queen, face as yet smooth, slighter of figure, active in posture, sitting side-saddle on her horse. Compositionally the statue is most successful, particularly the long folds of her skirt, entirely covering her legs and handing down in a great sweep of fabric. This work made something of a splash at the Great Exhibition.

The companion piece, towards the other end of St George’s Steps, is the equestrian statue of Prince Albert. Unlike Victoria, Albert is a relatively ageless figure and we are used to the way he generally looks in his statues. He sits very upright on his horse, which is itself a bold, proud creature well paired with its rider; a noble work indeed. There are duplicates of this statue in Wolverhampton and Halifax.

The sculptor, Thomas Thornycroft, father of the better known Hamo Thornycroft, was famous in his own time for this pair of statues in Liverpool, and the Boadicea in London.

C. B. Birch's statue of General Earle.

C. B. Birch's statue of General Earle.

The southern end of St George’s Hall is the end nearer to Lime Street Station, and at the advantageously sited corner is the bold statue of General Earle. He is shown in action, leading the way into battle, looking back at his troops, one gloved hand aloft gesturing towards the fight, the other clutching his unsheathed sword, treading an enemy shield underfoot. The sculptor was C. B. Birch, and the General Earle statue, with its highly active pose, is characteristic of a type favoured by Birch: other dramatically active sculptures by him include Lieutenant Hamilton, The Last Call, and Mazeppa.

Birch also made notable portrait statues, and in a central position on St George’s Hall Steps is his statue of Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield. What a contrast to General Earle in its sense of quiet movement rather than a surge of activity. The great Prime Minister wears a heavy robe, looped up over one arm in true Roman patrician fashion, half turning as if about to pace forward, sombre of expression and with eyes downward, contemplating some inner thought: Disraeli the political theorist rather than the orator. Surely one of the best statues of Disraeli.

Liverpool's lions, by W. G. Nicholl.

Liverpool's lions, by W. G. Nicholl.

Also central, but forward from the base of the steps, by the Cenotaph (see below), are four massive stone lions, which are the work of the sculptor W. G. Nicholl, and date from 1855. He also made sculpture for the pediment of St George’s Hall, based on designs by Alfred Stevens, but this, alas, was taken down after WW2, and the pediment as we see it today is blank. It included a central Britannia seated on a lion, a Neptunelike river god at her feet and a variety of allegorical figures on either side representing Commerce and the Arts. (For pictures of other Britannia statues, see this page.)

Happily surviving at the northern end of St George’s Hall is a collection of several Mermaid and Merman (Triton) lamp stands, excellent things, also by W. G. Nicholl. They are of the ‘split leg’ rather than single tail variety, and their twin tails are coiled around the base of each figure, with a skirt of frilly fins. The faces, male and female, are Classical, as are the massive torsos and arms. Up under the pillars of the building, thus protected from weathering, are the two original statues for the lampstands, thus holding up cornucopias but without lamps. Lots more pictures of mermaid statues are on this page, and mermen on this page.

There are 12 panels. Originally there were to have been rather more, 28 in all including some smaller ones higher up, and the sculptor Thomas Stirling Lee won the competition held in 1882 to produce them. His subject for the first six panels was The Attributes and Results of Justice, and they have rather lengthy individual titles, inscribed below each panel, such as ‘Joy follows the growth of Justice, led by Conscience, directed by Wisdom’ and Justice, having attained maturity, upholds the world, supported by Knowledge and Right’. But the remainder of the series after this first six panels was sadly truncated. As told in a turn-of-the-century account:

‘When the first panel was placed, considerable opposition resulted from ‘the child Justice’ being represented without clothing. This was intensified when ‘the girl Justice’ in the second panel was found to be also nude, and eventually the commission was cancelled. Mr P. H. Rathbone, who is always to the front in all that concerns the advancement of art in Liverpool, fought manfully, but without effect, until… he went the length of offering to defray the cost of the four panels required to complete the series, provided they were left undisturbed for two years before judgment was passed upon them, which proposal was accepted. The sculptures, each of which measures six feet by five feet one inch, harmonise admirably with the building, and emphasise the desirableness of proceeding with its due adornment. It remains to be seen whether Liverpool will appreciate the importance of going on with the worthy decoration of one of the finest buildings in the country.’

Sample panels by Conrad Dressler (left), and (right) C. J. Allen.

Sample panels by Conrad Dressler (left), and (right) C. J. Allen.

In the end, in 1895 the Liverpool Corporation commissioned a single further series of six panels, on the subject of National Prosperity. Two of these panels were by Stirling Lee, two by C. J. Allen, and two by Derwent Wood. Stirling Lee was clearly unrepentant over his previous use of nudity, and in one of his two panels (equally long-titled, on a nautical and fishing theme) managed a nude male figure, with a wisp of netting to avoid further scandalising the respectable burghers of Liverpool.

C. J. Allen’s pair of panels, (Liverpool employs labour and encourages art, and collects produce and exports manufactures etc), are among a number of works by this sculptor in the City, most famously the Liverpool Queen Victoria Monument. The Conrad Dressler panels (Liverpool imports cattle and wool, and food and corn…) are interesting because there is so little work by this estimable sculptor to be found on public display. The almost medieval ambience of his figures is characteristic.

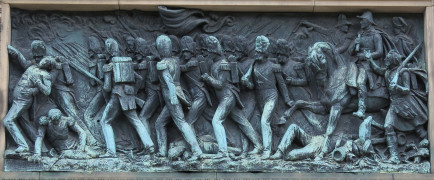

Beneath the steps in the centre, close to Nicholl’s Lions noted above, is the World War I Cenotaph. This was designed by Lionel Budden, a Liverpool architect and academic who also designed Birkenhead’s cenotaph. The two long bronze panels on the sides are the work of the Liverpool sculptor Herbert Tyson Smith, much of whose work is in the city, and who is not so familiar further south. Although active over a large part of the 20th Century, the sort of 30s-style figures found on the Liverpool Cenotaph are typical of much of his oeuvre. The one side shows a central coffin with mourners approaching from each side, thus a processional in composition, and the other side shows rank upon rank of almost identical soldiers marching to war. On the short ends are the coat of arms of the city, also in bronze, on a roundel with ribbons and a wreath of stylised flowers beneath; the treatment of the merman on the arms is very modern. The dates of both first and second World Wars are inscribed on these short sides, so that these coats of arms are likely of later date than the original Cenotaph friezes (which were unveiled in 1930).

Liverpool Cenotaph and details, sculpture by Tyson Smith.

All the way along the eastern side of St George’s Hall, glancing northwards we see the Wellington statue on his tall pillar, which stands across the road separating the great hall from the museum complex of the Walker Art Gallery and its companions, on a small area sometimes called St George’s plateau. As well as Wellington, this contains an ornate fountain, also noted below.

Wellington Column in the distance.

Wellington Column in the distance.

The Wellington Column first. London has its Nelson’s Column,

and Liverpool has Wellington. The pillar, raised up on a tall base and itself just over 80ft tall, is fluted and of the Doric order.

The architect was Andrew Lawson, brother of the sculptor The figure of Wellington, put up in 1865, stands with one leg forward beyond the base on which he stands.

He looks straight ahead, but I think the better view than the frontal one is the three-quarters aspect,

which shows a degree of movement to the figure, albeit we always end up seeing it rather foreshortened from below.

In one hand he holds a curved sword, in the other a scroll, and he wears over his tunic a cloak falling a little below the knee,

giving added gravitas. Like the majority of Wellington statues, he is hatless.

At the corners of the base of the column are four bronze eagles (if you like eagle sculpture, see this page),

and on the front of the base and so happily available for close viewing is a frieze, also by G. A. Lawson.

This shows a scene in the Battle of Waterloo, and includes about eight or nine figures in the foreground, and in low relief behind, rather more.

Wellington is seated on his horse at the right hand side, wearing his tricorn hat now, holding a spyglass,

his horse trampling between a fallen soldier and a collapsed cannon. Beside him strides a Scottish soldier delivering some news; in front are marching soldiers, wearing bearskin hats, and with those in the front line having their bayonets

pointing forwards. The far left of the scene shows a soldier supporting a collapsing comrade who has been shot,

while a colleague rests at his feet.

Eagle, Battle of Waterloo frieze, and close-up of Wellington. The Steble Fountain, close to the Wellington column, was paid for by Lieutenant-Col. Richard Steble,

a former mayor of Liverpool, and completed in 1879 (the date at the base is 1877). It is a classic mid-Victorian fountain,

on three levels. The top level consists of a shallow bowl with central figure of a mermaid (of the twin-tailed type), with below,

the turned column of the middle level with a wide bowl beneath, into which water splashes from above.

The edges of this bowl are decorated with grotesque heads of fishy monsters, and various shells, continuing underneath.

The lower layer includes the thick, octagonal base of the central column (an over-truncated square in cross section rather than a regular octagon),

around which sit four classical figures in a pool; between them on the central column truncated corners are further grotesque heads,

including one resembling a bear.

The four figures are apparently the sea-deities Neptune and Amphitrite (his wife, or in Greek mythology,

wife of Poseidon), and the more minor Galatea and Acis, doomed lovers from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. For the pictures

below, I chose a time when the fountain was under repair, so the figures could be seen without the obscuring water.

Neptune is depicted as the classical muscular figure with long, weedy beard and hair,

wearing a circlet of leaves or perhaps clamshells in his hair, draped around the legs, and holding what seems to be corn.

He turns towards Amphitrite, who is also seminude and holds some small item. She is of Classical physique,

large-breasted and with muscular shoulders and arms, and a great columnar neck.

Statues of Neptune, Amphitrite, Acis and Galatea. Galatea and Acis also turn towards each other with yearning, he an athletic youth,

supple rather than heavily muscular like Neptune, she a rather sweet, youthful figure seated with particular elegance,

and a most graceful, swaying rhythm to the pose of her body, head and limbs.

The fountain was cast by the ironfounders W T Allen and Co of Lambeth Hill, London from a French design, and other castings exist,

including in Boston, USA, now standing outside Massachusetts State House and called the Brewer Fountain, after its donor.

That version has a more ornate central shaft, but the figures are the same. Another version stands in the Jardin Anglais, Geneva,

and is mis-called the Fountain of the Four Seasons. Apparently casts also went to Bordeaux and Lyon though I have not verified this.

Attributions of the original sculptor vary, with the most likely case being that the original was a fountain designed by Paul Lienard,

a French sculptor, originally for the Paris World Fair in 1855, and reproduced or re-exhibited at the Paris Exposition of 1867.

Another attribution is to Mathurin Moreau, Val d’Osne, Paris.

While this page does not cover the sculpture on the frontages of the Museum complex to the north,

we may note that climbing back up the central steps of St George’s Hall gives a view of the building opposite to the east,

not as large of course, but with a splendid frontage: it is the former North Western Hotel,

also called the Lime Street Railway Hotel, which despite not being in red terra cotta, is recognisably by the architect

Alfred Waterhouse, and was built in 1868-71.

Dwarfed above the central portico among the dozens of windows are two standing statues in limestone.

The one on the left holds some small sticks or tools, her right hand on a shield with an olive branch against it,

at her feet a classical bust, on her head a castellated crown. The girl on the right is more exotic, with a leafy headdress,

a quiver of arrows, both hands probably on a paddle, a small crocodile wreathed round her feet and lower leg.

The two could perhaps be emblematic of Europe and the Americas, which would seem appropriate

for a Railway hotel.

Waterhouse's North Western Hotel, Lime Street, romantic evening view, and the statues. Statues in St John's Gardens behind St George's Hall // Liverpool's Queen Victoria Memorial // Municipal Buildings, Dale Street // Other sculpture in Liverpool

Sculpture pages // Statues in English towns

Visits to this page from 15 Nov 2013: 37,180

G. A. Lawson's statue of Wellington, facing and 3/4 view.

G. A. Lawson's statue of Wellington, facing and 3/4 view.

The Steble Fountain

The Steble Fountain, French late 19th Century.

The Steble Fountain, French late 19th Century.