Some sculptural things to find in Charing Cross Road.

Some sculptural things to find in Charing Cross Road.

In sculptural terms, the main interest, if not obsession, of these pages, Charing Cross Road contains a bronze statue to Henry Irving and the stone memorial to Edith Cavell, also three significant theatre frontages with sculptural decoration, and more minor ones. Also the National Portrait Gallery with its architectural sculpture, a good church exterior in the former Welsh Chapel, and a few bits and bobs of minor sculptural interest elsewhere as well as some buildings to note en passant. If you want Charing Cross itself, that is round the corner - see this page.

Charing Cross Road, together with Shaftsbury Avenue, were formed from 1884 (following an Act in 1877) to provide better north south connections to Charing Cross, the line of the new streets being drawn up by George Vulliamy, superintending architect of the Metropolitan Board of Works, and the Chief Engineer, Joseph Bazalgette. Charing Cross Road took in and widened two existing streets, Castle Street and Crown Street, so that there were retained some older buildings, but most of what we see dates from no earlier than the 1880s. It cut through a rather poor area, and the requirement to rehouse the displaced persons set by Parliament was responsible for another feature of Charing Cross Road – the vast Sandringham Buildings development, half of which survives on the east side.

The Survey of London states that ‘The general standard of design of the new buildings in Charing Cross Road and Shaftesbury Avenue was exceedingly low’, but today, we can look at it with kinder eyes and there is much to be appreciated in a street that retains a certain ambience, and is planted with tall plane trees pleasant to the eye. Again quoting from the Survey, ‘The original buildings lining Shaftesbury Avenue vary in height from four to six storeys, and in frontage width, but almost all have poorly composed fronts dressed with confused details, the materials generally being red brick with stone or terra-cotta. The style usually adopted was a hybrid Renaissance of Flemish derivation, with a frequent use of curvilinear or pedimented gable dormers rising against the slated mansard roofs, and domed or cone-capped corner turrets to emphasise the street corners. Noteworthy exceptions to this generalized description are the Palace Theatre by T. E. Collcutt, and No. 136 (the Welsh Chapel house) by James Cubitt.’ The four-to-six storey height has been retained in many of the newer buildings, and we can recognise the Queen Anneish red brick and stone buildings as a unifying theme cropping up in buildings along the street.

View of the lost corner to Oxford Street, photo by Google Street Maps.

View of the lost corner to Oxford Street, photo by Google Street Maps.

We start from the north end of Charing Cross Road, by Centre Point, where Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road meet. There is rather less at this end of the street than the lower part, from Cambridge Circus southwards, and less still now that the whole of the upper blocks have been obliterated to expand Tottenham Court Road Station for Crossrail. We may mourn the lost frontages – it is not so much that any single building was that good, but that together they made the corner to Oxford Street, and the entrance way on each side, rather grimy but atmospheric, to Charing Cross Road. I never took a photograph here, but fortunately found surviving views in Google Street View - see above. Here in this part of the street, though mostly on the other side, still in the 1970s and 80s there were remainder bookshops with deep basements under the road filled with art books – one of these was the original Any Amount of Books which expanded into a respectable chain before being taken over by Borders, which itself collapsed in the first decade of the new millennium. On the western side were somewhat tawdry entertainment and food shops. Architecturally, on this western corner was a rank of the red and white brick frontages noted by the Survey of London, and the Astoria Theatre, a 1920s effort by the architect Edward Stone, painted white and with a dome at the corner. On the eastern or right hand side the shorter frontage along Charing Cross Road (because of the Centre Point fountain and pool occupying the first 100 feet or so) included an arched passageway, blocked by fine ironwork and with a bearded keystone head above.

Side of Sheldon Mansions seen from Tottenham Court Road.

Side of Sheldon Mansions seen from Tottenham Court Road.

Our first surviving buildings on the left hand side are between Denmark Place and Denmark Street, and although of the red brick with white dressings style already mentioned, include a particularly tall central frontage, just three bays wide, but having above its five stories, a tall Renaissance gable with three further levels. It is called Sheldon or Shaldon Mansions and is no. 132 Charing Cross Road, dated 1889. There is minor carved decoration, in Renaissance style above the windows of the higher floors, including grotesque birds, faces and scrolling; similar designs flow round the corners of Denmark Street.

Details showing grotesque faces, 132 Charing Cross Road (Sheldon Mansions).

A few paces further on, Manette Street on the right hand side has no. 119 as a survivor, and on the opposite corner, Foyles, the famous bookshop. A diversion into Manette Street may be made to see the back of a charming little high Victorian Romanesque chapel, with little pointy roofs and miniature flying buttresses. It is the Chapel of the House of St Barnabas, dates from 1862-64, and is by the architect Joseph Clarke.

St Barnabas Chapel, Manette Street

Giles Gilbert Scott's Phoenix Theatre.

Giles Gilbert Scott's Phoenix Theatre.

Back in Charing Cross Road, nos. 114-116 on the left hand side, of the four storey red and white variety but now painted, by Roumieu and Aitchison (1888), was part of the extensive properties of Crosse and Blackwell on the street. It has lost its little balconies and ground floor decor, including the characteristic pedimented door, but has retained at second floor level four roundel heads. By this is a rather out of place 1930s Classical corner, very narrow, with four Corinthian columns round the curve, which is the Phoenix Theatre, by the eminent architect Giles Gilbert Scott.

114-116 Charing Cross Road, Crosse and Blackwell's, roundel heads.

Opposite is the old St Martin’s School of Art (107 and 109 Charing Cross Road), now vacated and under wraps, an ugly thing, but one which contains, if they are still there, modern sculptural plaques in the entranceways.

Tam-o-Shanter, 1896 over Crown Street houses, and pilasters from Cinematographic Theatre.

Tam-o-Shanter, 1896 over Crown Street houses, and pilasters from Cinematographic Theatre.

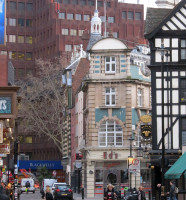

Continuing, back on the left hand or eastern side, Blackwells bookshop lurks behind a modern facade after that, but opposite it on the right hand side is the prominent former Tam o Shanter tavern, dated 1896 below the pediment, and apparently incorporates two original houses from Crown Street, which you will recall Charing Cross Road absorbed; on the left side of the pub, an unchanged Crown Street frontage survives, plain painted brick with a dormer. On the right hand side, a strange thing – a blank wall with four fluted ionic pilasters and one corner of a pediment – survivals of what was once the Cambridge Circus Cinematographic Theatre, opened in 1911, and subsequently called The Tatler.

Corner of Old Compton Street, Charles H. Worley's green faience, and block by Moor Street.

Back on the left, nos. 92 etc after Blackwells are of the Queen Anne red and white style, quite large, with bands of decoration at second floor level and minor carved monsters high up. Opposite, the corner with Old Compton Street (nos. 1 and 3 Old Compton Street) is completely different in green and white faience stripes, a bold thing of a type which might be found in Manchester. The architect was Charles H. Worley, the building dates from 1907, and there is an almost matching but less colourful block down Old Compton Street and swinging round into Moor Street (no. 12 Moor Street). Very bold, with alternating exaggerated voussoirs (the wedge shaped stones of a round headed arch) at and near the keystone position to each window. Good stuff.

Palace Theatre, Cambridge Circus, by T. E. Collcutt.

Palace Theatre, Cambridge Circus, by T. E. Collcutt.

And now we come to Cambridge Circus, the crossing point with Shaftsbury Avenue, and for those who have felt a bit cheated of proper sculpture thus far, we will do better from now on.

The noble Palace Theatre is the principle ornament of Cambridge Circus and the first of our three theatres with architectural sculptural decoration. It was put up for Richard D’Oyley Carte in 1904 as the Royal English Opera House, the work of the interesting architect T. E. Collcutt. The facade to the Circus, and somewhat round the corner to Shaftsbury Avenue, is in red brick and pink terra cotta supplied by Doulton’s of Lambeth. We see an imaginative Renaissance frontage, curved to the Circus, of many arched windows, with bands of low relief decoration. Three storeys rise above the ground floor, of which the first floor is of exaggerated height, and then we have two small towers, to left and right (there are further turrets along the Shaftsbury Avenue side), and a central gable, recessed, with further little turrets in front and two pairs of vile but lively free-standing terra cotta putti holding up bowls on the balustrade (if you like such things, see this page). At the summit of the gable stands a semi-nude female figure holding a torch (she is a rather good modern replacement of a lost statue).

Side turrent, summit figure, and putti in terra cotta.

Side turrent, summit figure, and putti in terra cotta.

The low relief terra cotta banded decoration includes seated elflike cherubs, and half figures and other grotesqued decorations, satyrs’ heads (more satyrs on this page) and strange beasts dissolving into arabesques. The viewer unfamiliar with such things may recoil at first, but as a Renaissance-derived ornament appropriate for a place of public entertainment, this is good of the type. The richest decoration is around the entrance, and includes full figure sculpture including a bacchanalian girl clashing cymbals.

Banded terra cotta ornament on the Palace Theatre.

The other buildings around the corners of Cambridge Circus, and those seen a little way along Shaftsbury Avenue, with their curved gables, are typical of the last decades of the 19th Century. The one below right was built by the Norwich Union Building Society, and is dated 1889.

Two of the buildings to Cambridge Circus, characteristic red brick with stone dressings.

Before leaving Cambridge Circus, we should look to the right of the Palace Theatre, where there is a little open space which splits to becomes Moor Street and Romilly Street. In the angled corner between these two is a particularly pleasing pub, architecturally speaking, currently called 'The Spice of Life', but built as The Cantons (originally 'The George and Thirteen Cantons' after an 18th Century tavern on the site), by an obscure architect (to me at least) called H. M. Wakley, and dating from 1898. It is in Flemish style, with a pair of prettily domed turrets towards Charing Cross Road, and a tall gable between. At the base of the gable stand two small carved monsters, and a close look at the different parts of the building rewards the viewer with two sphinxes, of a sort, and various relief sculptural decoration in Renaissance style. A worthy example of a particular type of pub building from the end of the 19th Century.

Flemish pub, The Cantons, 1898, by Wakley, and details.

A few steps south from Cambridge Circus, on the right hand side is the former Welsh Church or Welsh Chapel. It dates from 1887, is by the church architect James Cubitt (1836-1912, not to be confused with Thomas Cubitt, the famous builder), who wrote a book on church design in which he dismissed the standard aisle-and-nave found in most churches, and espoused a rather rotund design to allow the full congregation to see and hear the service: Christopher Wren had had similar preoccupations when he moved from the Catholic style of churches with a long nave and aisles suitable for processionals to the broader, more open churches allowing more access to the sermon which he felt appropriate to Anglicism.

Former Welsh Chapel, Charing Cross Road.

Former Welsh Chapel, Charing Cross Road.

Anyway,Cubitt's church in Charing Cross Road is in truth a rather splendid thing, and were it nestled in some village hollow or in the centre of a churchyard, instead of on the flat street frontage of a London street, it would be appreciated and visited for what it is, which is a powerfully massive, solid structure built in a Norman style, with grand portico, twinned windows and gables with blind arcading, little roofs and a great solid octagonal dome on top to give a lofty space within. The particular denomination whose church this was, was the Welsh Calvanist Methodists.

Sandringham Buildings by the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company.

Sandringham Buildings by the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company.

Opposite the Church is Litchfield Street, and from here all the way down to Great Newport Street and Leicester Square Station is the long sweep of the Sandringham Buildings. There was a matching building on the right hand side, now replaced by a modern development, and even the remaining one has a grandness of vision which compels the viewer to raise their eyes from the ground floor shopping street. There are over 30 bays, of mixed single and paired windows, with curved upper dressings of white-painted stone, the bulk of the building being yellowish stock brick with red brick horizontal courses rather lost behind the grime of a over a century. As noted at the top of this page, this estate was put up in 1884 to house working people displaced by the slum clearances needed to built Charing Cross Road, and the company which did this was the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company, one of the most potent of the Victorian model dwelling companies set up in London from the 1860s.

The London Hippodrome, by Frank Matcham.

The London Hippodrome, by Frank Matcham.

Opposite Leicester Square Station, with its characteristic dark purple tiling, rises the second of our three Charing Cross Road theatres with sculptural decor. It is the London Hippodrome, put up in 1899-1900, by the theatre architect Frank Matcham, originally for circus acts and spectacular shows, later as a more conventional theatre and music and variety hall. It is of massive size – four storeys above the ground floor, with a hollow dome rising to the corner, bearing a full size sculptural group of a Roman chariot drawn by a pair of rearing horses. The greater length is not to Charing Cross Road, but to Cranbourn Street, which is decorated with equal care; the other long side, to the narrower Little Newport Street, is plain.The design is very Frank Matcham – a grand Renaissance style with mixed motifs and a lightness of feel, covered entirely in terra cotta, and with much sculptural decoration.

Two views of Hippodrome Chariot, and the Roman Soldiers.

To see the chariot on top, the viewer needs to be at some distance from the building, so it is best seen as an iconic shape in the distance, from some way along Charing Cross Road, down one of the side streets, or in Leicester Square. A Roman soldier, legs and arms bare, a cloak around his back, and wearing a helmet with full Corinthian feathering, stands in his racing chariot, one hand holding the reins, the other raising his sword in a sign of victory. Both horses rear up to present a line of raised hoofs. Below, to left and right on the balustrade, are free-standing Roman soldiers, each with shield and long spear. A level down on the corner, a round window is flanked by a pair of high relief cherubs.

Some of the Hippodrome Caryatids.

As well as the corner dome, the skyline to Charing Cross Road is marked by a smaller tower at the other end, and a central raised up and curved gable, with a lion and unicorn resting against the sides (lots of lion sculptures on this page; unicorn sculpture is on this page). An equivalent gable on the longer side to Cranbourn Street bears two free-standing cherubs, and again there is a terminal tower with a little dome; on the side towards Little Newport Street, where the decor stops after just a couple of bays, there is a small protruberance bearing the date 1900. On the frontages lower down, there is much by way of minor architectural carving and ornament, but the main feature, and that which the viewer notices from close by, are the first floor terra cotta Caryatids between the windows at first floor (Caryatids of different sorts are described on this page). Some of these are in the form of a winged, armless half figure of a girl, wearing light drapes across the stomach, caught up under the breasts, and with a fold of drapery at the base of the stomach where the carved body ends and becomes the architectural shape, thus avoiding an awkward change. The others are male, point-eared satyrs, again armless and bat-winged. The figures vary in the detail, in their hair, wings, drapes and for the girls, their necklaces.

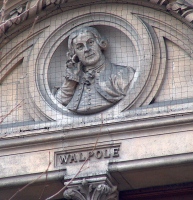

Across Cranbourn Street, the next block on the left after another entrance to Leicester Square Underground station is Wyndham’s Theatre, the third of our decorated theatre frontages. An Edwardian Classical frontage, this one, with a central pediment supported by Ionic pilasters, doubled up at the outer edges, and two wings, each with a wide arched window at first floor level and somewhat emphasised above so the effect is of a squat, solid tower to each side of the centre. A balustrade at the top supports a line of narrow-footed and necked vessels, giving a nice skyline.

Wyndham's Theatre, with pediment bust of Shakespeare.

The principle sculptural decoration is in the pediment, where we see a central bust of Shakespeare, flanked by a pair of reclining maenads, themselves flanked by a pair of cherubs and some foliage into the corners. The girl on the left is lightly and elegantly draped, and has one hand in her hair, the other on the base of the Shakespeare bust; she is likely to be an allegory of Acting or Dance, as her sister on the other side is assuredly Music: she holds a lyre, and is semi-draped. There is a pleasing balance between the two asymmetrically disposed figures. The cherub on the right continues the musical theme by holding a lute, with a violin and some brass instrument beyond; the cherub on the left carries only ribbons. Roughly finished, or over painted, but the composition marks this as the work of a highly competent sculptor, but there is no sign of a signature.

Sculptural details from Wyndham's Theatre.

Sculptural details from Wyndham's Theatre.

The theatre itself was the design of W. G. R. Sprague, a most significant theatre designer, though eclipsed by his master, Matcham, who designed the Hippodrome we looked at above. It opened in 1899, and the proprietor was Charles Wyndham, an actor-manager, who opened a second theatre a few years later. Carrying on down Charing Cross Road, we may note minor sculptural decoration on the next block on the left, including three sculpted heads, probably survivals of rather more, and on the next block, past Cecil Court, several survivors of the red-and-white style we are by now familiar with, the one with most (still minor) decoration being nos. 12-16, called Garrick Mansions, which has little grotesque heads, bands of grotesques and arabesques, lions’ heads, and at the top, a Baroque gable bearing the initials JH in a wreath of carved leaves, grotesque heads and mini-cornucopias below, none of which can really be appreciated from the street far below without visual aid. No 19 more or less opposite is a stone fronted equivalent, with no. 17 next to it a single-bayed oddity with patterned faience.

The street then opens out into a pleasant, leafy triangle. On the right hand side, on Orange Street, are several late Victorian or Edwardian survivors, the most interesting being above Cass Arts at no 13, in red brick and pink terra cotta with an emblem of a closed gate; more jolly, lightly decorated Queen Anne gabled buildings occupy Irving Street round to the right. The Garrick Theatre, big, broad, and classical occupies the whole left hand side of the open space, with a single band of repeating carved pattern above the Corinthian columns, of no sculptural interest. The theatre was financed by W. S. Gilbert, of Gilbert and Sullivan, and opened in 1889. Walter Emden was the architect, with C. J. Phipps, and these are two more of the better known theatre designers of the time.

Garrick Theatre, by Walter Emden with C. J. Phipps.

The far side of the triangle is the side of the National Portrait Gallery, and in front of this is a standing statue of Henry Irving in bronze – rare indeed to find a Victorian statue of an actor. The sculptor was Thomas Brock, sculptor of the Queen Victoria Memorial, and the work dates from 1910. Irving is shown declaiming, standing in – I hesitate to use the word – theatrical pose, holding a sheaf of paper in one hand, his other hand on his hip. A sensitive and characterful face, which would have been critically appraised by many for a true likeness. The base is decorated in a late art nouveau idiom, and incorporates the monogram HI.

Henry Irving statue by Thomas Brock, and two of the roundels modelled by Frederick Thomas.

The side of the National Portrait Gallery building, and the frontage onto Charing Cross Road, incorporates a series of roundels of great British personalities – politicians and statesmen, and artists including Chantrey, Hogarth, Kneller, Thomas Lawrence, Lely, Vandyke, Holbein, Roubiliac, and Reynolds, some rather swallowed in the foliage of the Plane trees. The Charing Cross Road frontage also bears a coat of arms, and a large stone figure of Britannia. The sculptor of the medallions was Frederick Thomas, working from medals etc in the British Museum.

The block on the left after the Garrick, also classical, sweeps round to the left into the open space called St Martin’s Place – note the nice keystone heads facing from that building onto the Place – and bring Charing Cross Road to an end, with the view ahead dominated by the spire of St Martin in the Fields. Our final sculpture is the group in commemoration of Edith Cavell, in the centre of the Place, the work of the sculptor George Frampton. He is most familiar to us as a New Sculptor of allegorical figures and the Peter Pan statue, but he made several memorials after World War I, and this one was put up in 1920. The portrait statue in white stone, robed and dignified, stands in front of a tall granite plinth on which is a Guardian Angel holding a small child; the rear has a low relief of a proud British lion trampling the defeated enemy snake.

Aspects of George Frampton's monument to Edith Cavell.

North and West to Oxford Street // or due North to Tottenham Court Road or North-East to St Giles in the Fields // // Continue south to Trafalgar Square // West to Leicester Square // East to Charing Cross itself

Visits to this page from 13 Mar 2014: 15,173