Chelsea Embankment stretches from near to Brompton Cemetery in the west, something over a mile eastwards to Chelsea Bridge and the rail bridge next to it. The path is mostly due east, with the curve at the beginning allowing fine views of the river and Battersea Park on the south side, and at the end, views of the iconic Battersea Power Station. Along the way are a series of things of sculptural interest, including various full figure statues, both portrait and ideal, a bit of architectural sculpture, and Chelsea Old Church, which while not described on this page, is full of excellent monumental sculpture. The walk, which perforce has to go along the main road, is best made in the summer in the morning, with the sun to the south high in the sky.

We start at the west end. The nearest station is at Imperial Wharf on the London Overground; an alternative is a 15 minute walk from Earl s Court Station, southwards along Earl s Court Road and then Redcliffe Gardens and its southern continuation, leading into Cremorne Road, which sweeps round gently into Chelsea Embankment. Right at the beginning is little Cremorne Gardens facing onto the river, and we start here for the river view and to see a piece of ironwork.

The Cremorne Gate, and details.

The original Cremorne Gardens, named after Lord Cremorne, (Thomas Dawson) are long gone they were a pleasure gardens of the early 19th Century, somewhat in the vein of the earlier Vauxhall Gardens. Close to the pier lived Turner, the painter, for the period up to his death in 1851. His contemporary, John Martin, best known for his various Apocalyptic scenes (which can be seen in Tate Britain) lived nearby, as did Brunel. What we see now is a rather small open space, but within it is a gate, now known as the Cremorne Gate, which survives from the original garden, though it has been moved. It is a large cast iron affair, dating presumably from early Victorian times, with a curly design round the Royal Arms at the top, hefty pots on the gateposts each with a gilt acorn, and lion heads on the gates themselves. The prominent church steeple south west, on the other (south) side of the Thames as it curves round, is St Mary Battersea.

Residences of JMW Turner, and the sculptor John Tweed.

Residences of JMW Turner, and the sculptor John Tweed.

We exit and commence to walk eastwards along the Chelsea Embankment, on the south side towards the River. Immediately after the very modern buildings on the north side, the first group of rather exuberant older houses contains that where Sylvia Pankhurst lived, marked with a blue plaque; a couple of minutes earlier, just past the entrance to Riley Street, is the nondescript house of John Tweed, the early 20th Century sculptor (see picture above: that next to it on the left is the house of the painter Philip Wilson Steer).

Whistler, modern statue by Nicholas Dimbleby.

Whistler, modern statue by Nicholas Dimbleby.

The nearest bridge we can see, long, low, flat, is Battersea Bridge. Just by it is a tiny green space with shrubs, among which is hidden our first statue, a modern one of the American artist James McNeill Whistler. It was put up in 2005, and is the work of the sculptor Nicholas Dimbleby, who has produced several public works, of which the only other one I have actually seen is a roundel of Wesley in St Marylebone Church, Euston Road. Whistler is shown rather young, and the sculptor has contrived something of a dashing bravado appropriate for the subject.

Bazalgette's Battersea Bridge.

Battersea Bridge is rather plain excepting the ironwork by the supporting pillars or piers. It dates from the 1880s, replacing an earlier wooden bridge, and the designer was Bazalgette, the engineer who built both Chelsea Embankment itself and the Victoria Embankment. It does provide a vantage point to view the more interesting suspension bridge which comes next.

Crosby Hall, detail of sculptured sea-stag, the Hall before it was moved, and Crosby's monument.

Just beyond the bridge, the splendid building on the north side of Chelsea Embankment is Crosby Hall, dated 1466, put up in Bishopsgate in the City of London (where John Crosby's tomb, shown above, still stands in the Church of St Helen Bishopsgate), and transported here in an act of inspiration in the early 20th Century. The gateway includes interesting architectural sculpture: two heraldic lions on pillars to the sides, high relief carvings of sea-stags in the long spandrels above the Tudor doorway, grander sea-stags above at the base of the charming window, flanking a shield at arms with a single sea-stag in low relief, with trident, a device reproduced in larger, deeper relief above the window. What are these sea-stags? They are related to the mythological hippogriff, and like that beast, may be found in Roman mosaics along with other half-animal half-fish creatures. Thus we have a scaly body with long, curled over tail, the head and breast of a stag, with something of a mane, and the front legs of a deer, but with flippers instead of hooves, and lateral fins on the upper arms. The deep body appropriate for a stag means that they are somewhat more bulky than the fishy lines of, say, a mermaid, yet they have an integrity and conviction that makes it easy to imagine them swimming down the Thames. Really rather rare, I cannot think of another example of sea-stag sculpture in London.

Across the road (Danvers Street) we see the brick tower of Chelsea Old Church, and in front of it as we approach is a sunken garden, which we have to cross over and visit, along with the other sculptural work around the Church.

Gilbert Ledward's Awakening, and the Epstein panel.

The sunken garden, known as Ropers Garden, has as its central feature a charming statue of an ideal female nude, called Awakening. She stands with arms above her head, which is angled upwards and turned towards the side, her eyes still closed, as if about to take her morning stretch. Her legs are slightly bent, and she leans a little forward, adding to the air of dynamism, youth, and suppressed energy. She is muscular rather than slender, but the upward movement of her arms means that something of an emphasis is given to the flatness of her stomach and the delineation of her ribcage. She appears graceful and elegant from all angles, and is a fine work by the sculptor Gilbert Ledward, dating from 1923. Ledward s large oeuvre includes a number of nudes, and another of them is in Sloane Square, also in Chelsea.

Also in the sunken garden is a stone panel by Epstein, another female nude, appearing headless, rather raw and a bit disturbing, a work of 1950.

Two views of Chelsea Old Church, as it used to be.

Two views of Chelsea Old Church, as it used to be.

Chelsea Old Church was bombed extensively only the smallest bit of wall survives from before the War, but a herculean effort by W. Godfrey, the architect, put back together the broken monuments which can be seen today; the Church is open once a week, and its website should be consulted for current opening hours. Here, we note only that older pictures of the Church show a number of monuments affixed to the outside of the building (above left).

Figures on the Coalbrookdale lampstand, 1874.

Figures on the Coalbrookdale lampstand, 1874.

Just by the Church is one of two lampstands, dated 1874, made of iron, with sculptures of two boys climbing up them, and twisted cornucopias at the base. The lower boy, nude, climbs upon the plinth, one tiptoe still resting on the edge of one cornucopia, one up stretched upwards to where the other, smaller boy, reaches towards him; that boy has one foot upon the shoulder of the lower figure. A well composed group, cast by the famous Coalbrookdale Iron Foundry.

Close to this is the Sparkes Fountain, put up by his widow in 1880, he having died in 1878. This is a good example of a Victorian civic fountain, made in hard granite, of obelisk shape above the water basins, and with a lamp on top. The inscription notes that Sparkes was a judge at Madras in the East India Company s Civil Service.

Thomas More statue, and his long-gone Chelsea residence.

Thomas More statue, and his long-gone Chelsea residence.

Directly in front of the Church is a seated modern statue of Thomas More, friend of Henry VIII who was ultimately beheaded for treason. He is shown in symmetrical pose, hands clasped, enveloped in his thick robes, and with a wide furred collar. The figure is black, with gilt face and hands. There is not much in the way of interest to the drapery, so the figure is rather too solid, but nevertheless, and interesting piece. It dates from 1968, and the sculptor was Leslie Cubitt Bevis; I am not aware of other public sculpture by this artist.

Aspects of the Hans Sloane memorial. by Chelsea Old Church.

Just to the further side of the Church is the Monument to Hans Sloane, founder of the British Museum, a great carved stone pot under a round-arched canopy, put up by his daughters following his death in 1753. The egg-shaped pot is clasped by two long snakes, entwined somewhat with each other in harmonious symmetry. They are pythons, really rather rare in British sculpture (see the page on Snake sculpture). The sculptor of this monument was Joseph Wilton RA.

The Albert Bridge, with Battersea Power Station behind.

We proceed, noting the view ahead of the rather decorative Albert Bridge, built as a suspension bridge.

On the north side after the Church is Chelsea Embankment Gardens, a narrow strip of green between the Embankment and Cheyne Walk, in two sections. Within the first section we have a significant portrait statue.

J.E. Boehm's statue of Carlyle.

J.E. Boehm's statue of Carlyle.

The statue of Carlyle, by the sculptor J. E. Boehm, is regarded as one of his most important works. The thinker and writer is seated, in modern dress but swathed in a long coat somewhat too large for him which gives the effect of drapery, with the sculptor making much of the folds and creases in the heavy fabric. Carlyle is shown at an advanced age, with lined, thoughtful and sombre face above a rather wild beard, truly the portrait of a philosopher.

Boy with Dolphin, by David Wynne.

Boy with Dolphin, by David Wynne.

Next, as we come to Albert Bridge, we see, again on the north side, at the corner with Oakley Street, the large sculptural group entitled Boy with Dolphin, an archetypical work by the modern sculptor David Wynne. He has a number of light, airy statues in London and elsewhere, and rather favoured youths and dolphins. The dolphin, arched as if leaping from the water or racing through it, is held by the dorsal fin by the hand of the boy, who soars above and behind the animal, his hair streaming backwards. The effect is of speed and vigour.

Statue of Atalanta, by Derwent Wood.

Diagonally opposite, by the Bridge, and easily walked past if on the other side of the road, is the splendid statue called Atalanta, surely one of the most splendid sculptures of the female nude to be found on London s streets. Atalanta was the ancient huntress and fleet runner, follower of the Goddess Artemis and the only female Argonaut. In paintings, she is often shown picking up the golden apples of Aphrodite, from a famous race she ran and lost with Hippomenes. But here she is simply standing in an easy, informal pose, no apple in sight, her head turned one way, her lower arm on the other side raised in a spontaneous gesture. She is fairly muscular and solid of leg and arm, not at all like the conventional statues of that other famous huntress, the goddess Diana, who tends to be slender and girlish. Her face is good, ideal, but, it must be admitted, Edwardian rather than particularly Classical (see image at top of page). The siting of the statue, by the path alongside the river is such that she can be seen from almost all sides. Derwent Wood was the sculptor, and a marble version of the statue, dating from 1907, is in Manchester Art Gallery.

We have already noted Albert Bridge, which in the nature of bridges looks better from the side than obliquely. It was built in the early 1870s to the design of the engineer Rowland Ordish, strengthened by the engineer Bazalgette, whom we met as the designer of Battersea Bridge, and again in the 1970s with extra piers at the centre.

After the bridge, the second portion of Chelsea Embankment Gardens contains several pieces of sculpture.

First is the second of the pair of Coalbrookdale lamps, described and pictured above.

Then, in the green space is The Boy David by Edward Bainbridge Copnall, a nude male figure in a modern idiom with oversized upper body and head, holding his downward-pointed sword, and with the head of Goliath at his feet. The statue, perhaps half life-size, stands on a red granite pillar.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, by Ford Madox Brown.

Next, a portrait bust of Rossetti, painter and poet, who lived in Cheyne Walk, a rare sculpture by the painter Ford Maddox Brown, his one time master and fellow-traveller, though not member, of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The bust is within a niche on a marble fountain, designed by the furniture designer and architect J. P. Seddon. Rossetti is depicted in a scholarly robe, writing with a quill pen on an easel, resting on two books by Rossetti Dante and his Circle, and Ballads and Sonnets. The memorial was put up in 1887, thus a few years after Rossetti s death in 1882.

Then a portrait bust of the composer Vaughan Williams, on a short pillar, this being very modern, put up in 1912, the sculptor being Marcus Cornish, who also made the large stag sculpture in St James Square.

Crossing back to the south side of the road, for the fine view back along the river to Albert Bridge, we can already see eastwards, in the direction we are going, the other suspension bridge, Chelsea Bridge, and, over the trees and round the southward bend of the river, the great towers of Battersea Power Station. We may note here, having not done it earlier, the characteristic cast-iron lampstands, and also the iron benches, designed by Vulliamy, with sphinx designs.

Pagoda in Battersea Park, seen from Chelsea Embankment.

Pagoda in Battersea Park, seen from Chelsea Embankment.

Continuing, on the north side are various red brick and terra cotta terraces, with some minor decorative ornament. We cannot see into Chelsea Physick Garden whose edge is against the Embankment road, wherein is a statue of John Sloane by J. M. Rysbrack (or at least a replica of it), whose memorial we saw by Chelsea Old Church. But looking across the river southwards to Battersea Park, we can see the Peace Pagoda, with a statue of Buddha, erected in 1985.

We have one more significant sculptural work to see on Chelsea Embankment, after some distance walk further. On the way, on the north side we see the enormous Royal Hospital Chelsea, founded by Charles II to house the retired soldiers known today as the Chelsea Pensioners, and built by Christopher Wren to a vast scale.

Chelsea Hospital, by Wren, and Grinling Gibbons' statue of Charles II.

Looking from the gate towards the distant facade, the obelisk nearest to us is the Chillianwallah Memorial, commemorating an 1849 battle of that name during the Second Sikh War, designed by the Victorian architect C. R. Cockerell and put up in 1853. Somewhat behind this we can glimpse the gilded statue of Charles II, dating from 1676, by the sculptor and wood carver Grinling Gibbons - a close up is above.

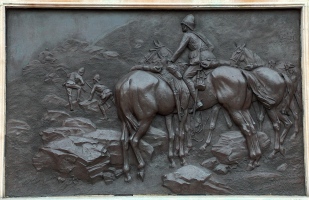

Relief sculpture of the Carabiniers monument, by the sculptor Adrian Jones.

Relief sculpture of the Carabiniers monument, by the sculptor Adrian Jones.

And then we come at last to Chelsea Bridge, end of Chelsea Embankment. It dates from the 1930s, replacing a mid-Victorian bridge. On the north side, on the corner with Chelsea Bridge Road, is our last sculptural work, the Carabiniers Memorial, to the cavalry who fell in the Boer War, dating from 1905. It incorporates two panels listing the fallen, and a large central panel by the sculptor Adrian Jones. The low reliefC scene is rather poignant: in the foreground is a mounted Carabinier, with several horses, facing away from us, towards two dismounted troops their horses presumably being those held by the foreground figure are cautiously ascending a rocky hill, bayoneted rifles at the ready; dimly glimpsed near the summit is another figure, taking cover as he peers over towards the unseen enemy. The sculptor Adrian Jones specialised in horsy subjects, most notably the Quadriga atop Constitution Arch at Hyde Park Corner.

And this is the end of our sculptural walk. From here, the visitor can proceed northerly along Chelsea Bridge Road, arriving eventually at Sloane Square, or walk under the railway bridge from where the best views of Battersea Power Station may be obtained as the river curves and then head north along Lupus Street and zigzag through the streets to Victoria Station.

View of Battersea Power Station from end of walk.

View of Battersea Power Station from end of walk.

London sculpture // Sculpture pages

Visits to this page from 29 Jun 2014: 493 since 9 November 2025