Nicholas Stone the Elder (1586/7-1647)

An important and most successful early 17th English Century sculptor, who made many splendid church monuments, and has many works scattered across Great Britain.

The sculptor Nicholas Stone is by far the best known early 17th Century English sculptor, also working as an architect, builder and mason. He was very prolific, and because his notebook from 1614-41, and an account book for 1631-42 survive in the Soane Museum, there is a great list of most of his works, mostly church monuments which have survived, often in perfect condition. So his work is better known than other sculptors of the time, to whom much is 'attributed to' rather than absolutely known to be their work.

He was born in Devon, his father a quarryman, and in about 1603 apprenticed to a Dutch sculptor, Isaac James, working in Southwark. What could be more natural than that when in 1607 Hendrik de Keyser, the Dutch architect-sculptor, master mason to the City of Amsterdam, came to London, the young Stone should be introduced to him, and return to Holland with him as an apprentice. And what more natural than that by and by he marry his master's daughter Mary de Keyser.

The marriage, and Stone's return to England, were in 1613, and he set up in London near St Martin in the Fields and joining the Masons' Company, by the mid-1620s establishing a large workshop in Long Acre. He achieved rapid success with many commissions, as both a monumental sculptor and as a mason, in which latter capacity he worked as builder for Inigo Jones' Banqueting House in 1619-22. In 1626 he became Master Mason at Windsor Castle, later becoming Master Mason to the Crown, and Master of the Mason's Company for 1632/33 and 1633/34. It all went very well until early in the following decade, when the Civil War effectively closed his career.

His notebook and account book contains around 80 identified monuments, with surviving pieces from as early as 1615 all the way through to 1642, augmented by a few identified from other sources, and around 50 further attributions with varying degrees of plausibility and evidence. Adam White, who wrote the definitive piece on London tomb sculptors, felt only about a third of these attributions could be relied on.

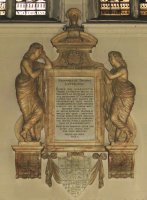

Sutton monument in the Charterhouse.

Nicholas Stone's surviving pieces include some of the largest, grandest monuments with several full sized statues. We have effigies flat on their backs with hands raised in prayer, as had been done for hundreds of years (e.g. Lionel Cranfield, Earl of Middlesex and wife Anne, and the Sir George and Mary Villiers monument, both in Westminster Abbey, Thomas Sutton in the Charterhouse, Sir Edward Coke in St Mary's Titteshall, Norfolk), and Elizabethan or Jacobite kneeler monuments (such as Lord and Lady Knyvett in St Mary's Stanwell, and Lord and Lady Fauconberg in St Michael's Coxwold, Yorks, and the Belasyse monument in York Minster). Also the more modern reclining effigies, comfortably resting on their elbows (e.g. Dudley Carleton, Count Dorchester in Westminster Abbey, and the Morison monuments in St Mary's Watford), and standing allegorical figures in Classical drapery, as in the Lyttleton monument in Magdalen College Oxford.

Half figures and busts by Stone.

Lower down the scale, we have numerous busts and half-figures by Stone, outer London examples including Sir Thomas and Lady Merry in St Mary's Walthamstow, and Martha Palmer in St Andrew's Enfield, and the Wilbraham monument in Monken Hadley. And some examples with a portrait bust as simply one element of a vast architectural monument, as in Sir Robert Drury in All Saints Hastead, Suffolk. And finally a goodly number of tablets without figures, but still including minor sculpture, festoons of flowers, winged cherub heads and the like.

Painted kneeler monument by Stone.

Stone's figures are generally in white marble and unpainted, though there are exceptions, as in the example above. Even his busts and kneeler figures, in the main, seem to be real portraits, with their own personal features and expressions, rather than the bland and impersonal faces found on so many Tudor and Stuart monuments. His carved hands are particularly expressive. He favours much detail, with low relief carving of damask and fur and subtly captured folds and surfaces to his drapery. His architectural surrounds are carefully in proportion to the figures, and we never have the sense of too much weight above, or a discordance of composition or line. Aside from the white marble figures, Stone often uses a range of coloured marbles and alabasters, above all the favoured black and red-brown of the early 17th Century.

Lyttelton monument - Classical figures by Stone.

Stone's other sculptural work includes a number of surviving church fonts (examples are St Andrew Undershaft in the City, St Margaret's Westminster and St John Evangelist at Stanmore), and also sundials and chimneypieces, difficult to attribute with certainty, and he had some public sculpture such as figures for the Royal Exchange which have mostly perished. The fonts are elegant but of course limited in sculptural interest, so that it is his church monuments which stand as his legacy today.

Stone's work as an architect is also mostly gone. Noted above is his building of the Banqueting House, but that was entirely to Inigo Jones' design. The Water Gate on the Embankment is attributed to Stone, though again he may have built to Inigo Jones' plan, and the lions are normally attributed to Balthazar Gerbier (though Vertue has the right hand one by Stone). In Oxford, Stone designed the triple-gateway to the Physick Garden (not the statues) - see this page, and designed and carved the entrance porch to St Mary's Church up the High Street there (see picture above). Elsewhere, there are a few bits ascribed to Stone, and some drawings of his demolished works, but not I think any surviving complete building designed by him.

Nicholas Stone had three sons. We have Henry Stone (also a painter), Nicholas Stone the Younger, and John Stone, all of whom became sculptors, though their oeuvres are small, and Henry and John took on their father's business after he died (Nicholas the Younger died in the same year). And there are 11 assistants known to have been employed in the Long Acre workshops, none of whom ever rose to fame.

Nicholas Stone's own monument, recorded as being by Henry Stone, was in St Martin in the Fields, and does not survive, but a drawing of it exists and the inscription was recorded by Vertue:

'To the Lasting Memory of Nicholas Stone Esqr. Master Mason to his Majestie. in his Time esteemd for his knowledge. in Sculpture & Architecture. whch his works in Many parts do Testifie. and (though made for others. will prove Monuments of his Fame. he departed this life on ye 24. Of Aususte 1647. aged 61. and lyeth buried near the Pulpit in this church. Mary his wife & Nicholas his sonne lye also buried in the same grave. she died Nov. 19 & he on the 17. Sept. 1647. H.S. Posuit.'