Cherub sculptures can recall the sentimental, cloying sweetness of much Victoriana, and depart far from the ideal human form, whether slender Classical girl or male athlete. But cherubs are so widespread in architectural sculpture that we are compelled to look at them.

What do we mean by Cherub? Today, we use the word Cherub fairly interchangeably with Putti, Cupid, Eros, and Amorini. The winged infant children popular in Greek and Roman art are generally termed Putti, a plural word from the Italian ‘putto’). They are usually male, and often one will appear in Greek art as a little Eros accompanying Aphrodite, sometimes Bacchanalian. The Roman version is a Cupid, son of Venus, goddess of Love, and herself the Roman equivalent of Aphrodite. But ‘Cherub’ feels more comfortable to the English speaker for the singular, as Putti is strictly plural but ‘Putto’ is unfamiliar. After Classical times, they were not so popular, in sculpture at least, until Renaissance times when they returned in force as a recognised part of Christian art, sometimes indicating a young angel, often musical, but generally decorative rather than greatly symbolic of anything in particular. Renaissance cherubs are most often termed ‘Amorini’, and use of the term Cherub does need to be distinguished from ‘Cherubim’ which refers to a specific type of angel in early Christian art. They were again revived in the 19th Century, lasting through Edwardian times before going into sharp decline after World War I. Allegorically, if not religious, our 19th and early 20th Century Cherubs or Putti may be linked with Love (Eros or Cupid –generally winged and with a bow - for the Statue of Eros, see this page), or reflecting various of the normal grown-up allegorical statues. In the latter form, during this period they were often used when seeking a light-hearted or more baroque version of a classical building, or on a frieze which was relatively low in height where the squat shapes of the putti could be more distinctly seen from down below than more slender allegorical girls. On this page, we will generally use the popular term ‘cherub’.

Cherubs and cherub heads, St Mary le Bow Church.

Cherubs and cherub heads, St Mary le Bow Church.

So far as these pages are concerned, we can start in the late 17th Century with Wren’s City Churches, which used a variety of cherubs on the exterior. The portico of St Mary le Bow above nicely illustrates the type – the cornice of the Classical door has a line of winged cherubic heads, and above, two full-figure cherubs flank a central oval window, with a further winged cherubic head above on the arch keystone. The line of little heads are not identical, varying most in the hair and shape of the lower face. The head at the top is larger and protrudes further from the backing stone. The two full-figure cherubs are really rather corpulent, with not just a plumpness but a heaviness to the flesh of cheek and breast and stomach. One plays on a musical instrument, the other reads from a book, presumably the Bible. A few other examples from Wren’s ecclesiastical architecture are below.

Cherub carving on Wren churches.

In 19th Century architecture, perhaps the commonest use of the full-figure cherub, as opposed to the winged head (to which we shall return), is as a pair, supporting a shield or cartouche or emblem. The first example below, from Electra House, London, is typical – the cherubs are standing, both supporting a cartouche with their two hands, symmetrically disposed but not exactly so; in this example, the sculptor – Alfred Drury – has used their wings to help fill the surrounding space. The second example is very unsymmetrical – one cherub leans inwards to hold the top of a cartouche, the other walks away from it; in both cases the line of the body and limbs nicely follows that of the cartouche. And below right, another symmetrical example, rather ornate, with the two cherubic figures pushing inwards on a cartouche bearing an emblem. Here the bodies are heavily sculpted, and there is much variety of detail, for example in the locks of the hair.

The cherubs need not, of course, be standing. Below left are a seated pair beside a globe, one facing outwards, the other turning his body inwards, so that the legs are similarly positioned, but all else is varied. Again, much modelling to the bodies. The second example below has two reclining cherubs, distinctly male and female – most cherubs are male, but the odd little girl does appear, most often in a pair as here; the example below right, also seated, shows a pair of what certainly seem to be little girl cherubs.

Seated cherubs, male and female.

And below is another example from London, a corbel on the Wigmore Street Debenhams building, with two little girl cherubs nicely floating amidst garlands, a cartouche and acanthus leaves. Accomplished work by Doulton's.

We don’t have to have a cartouche to have a free-standing cherub. Below left, a seated cherub of avarice, clutching his hoard of flowers to his body, as a terminus on a pillar. In the centre, a sandstone cherub, much worn by time, on a pilaster to a roof – even in his battered state there is a certain pathos to this example. And below right, a seated cherub seated at the edge of a building, holding the string course in a sort of architect’s pun.

Seated cherubs, free-standing.

Here are a couple of examples of cherubs with a woman as some sort of Aphrodite figure. To the left is a nice example by the sculptor Henry Poole, with two cherubs each holding a cornucopia, at the feet of an enthroned proud female with a crown of laurel. And below right is a seated female again with a pair of cherubs, one with cornucopia, the other with a sheaf of corn. Rather bacchanalian this one, but the cornucopia is here a sign of prosperity appropriate for a shopping arcade - this is an entrance to the Royal Arcade off Old Bond Street.

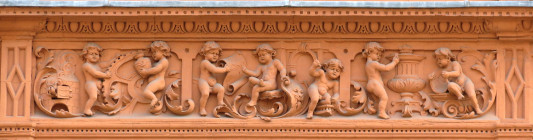

The Royal Arcade example takes us to cherubs in high relief, of which there are a plethora. Below are a few examples. First on the left, a rather scientific example, examining a range of curves on a chart, perhaps temperature as indicated by the thermometer at his feet - this one is signed by the sculptor, S. Alexander, unusual on such a small panel. Then a pair with very short legs but long arms crowning a queen. A frieze of pastoral cherubs with one riding a sheep, one reclining on a pile of hay while a third blunders through the corn, and a fourth playing the pan pipes while his dog looks on. Next a vertical panel in terra cotta with another musical cherub playing the cymbals. And a glazed tile example, unusual in composition in that the cherub in front partially obscures the two in the rear.

Cherub sculpture in high relief.

More terra cotta friezes with cherubs below. A whole choir in pale terra cotta below left, unfortunately only viewable at an oblique angle. Then an example showing artisan cherubs, with kiln and decorated pots. This is an example which could easily have been done in more serious vein with grown up craftsmen, so the cherubs are either to make best use of a shallow frieze space, or aim to have a degree of frivolity and light heartedness. And below right, a dark red terra cotta example, showing a dignified kneeling cherub with hanging drapes in front of a niche.

Cherub friezes in terra cotta.

Continuing with the theme of cherubs associated with architectural elements, below left are examples of cherubs in architectural pediments, where they fit easily towards the narrow corners. To the right we have a spandrel with two cherubs emblematic of Literature, and a double spandrel with a most angelic cherub which, with its fine modelling, is a serious piece of art.

Architectural cherubs - pediments and spandrels.

Our cherubs thus far have been mostly of the plump infant type, but we should note that there also exists an older type of cherub, with the longer limbs and more muscular body of a youth rather than a baby. Below left is an intermediate pair of putti, with something of the infant, something of the youth in their bodies. Next, a pair of angelic cherubs supporting a cartouche, with a remaining chubbiness but a definite increase in height. In the third example the chubbiness has become muscle, and the legs and arms are of almost adult proportions, though the head is still over-large. And lastly, an adolescent angelic cherub, with slightly sullen expression and almost grown-up proportions.

Cherubs as youths, not infants.

I said we would return to winged cherub heads, and below are some further examples. To the left, a joyful or singing cherubic head above a cartouche. Then a rather symmetrical example, where the wings have become the almost acanthus-like borders of a cartouche, most Arts and Crafts in motif. Next, a rather sweet cherubic head with Halo, from the outside of a church. And a pair of heads flanking another cartouche, combined with symbols of plentitude.

More examples. Below left we have a head with has six wings in all, or three pairs, and is safely ascribable to the architectural sculptor Gilbert Seale. Then one with completely separated wings, and little ribbons to add to the delicate, Louis quatorze look. And by contrast a strange keystone cherubic head, which has more of a snout than a nose. Incidentally, in funereal monuments, the ethereal winged cherub head has its grim counterpart in the winged skull, of which examples can be seen on this page part way down.

We end with examples of half-figure and grotesque cherubs – grotesque not in the sense of being ugly, but in the artistic sense of a figure whose body is subjected fully to ornament. Below left are a pair of half figure cherubs, beautifully rendered in terra cotta, grouped with acanthus leaves, scrolls and corn around a central window. Then a pair of not dissimilar half figures carrying festoons of hanging fruit and flowers – this also showing the facility terra cotta provides to the artists working with it. And below right, pairs of grotesque cherubs, of female appearance, as part of a decorative scheme above coupled windows.

Angel sculpture // Mermaid sculptures // Winged cherub heads

Architecture pages // Sculpture pages

Allegorical sculpture // Introduction to church monuments

Visits to this page from 13 Mar 2014: 60,772