St Helen Bishopsgate is a precious survival of a pre-Fire of London City church. It is in fact two churches, an ancient Parish Church and the adjoining Benedictine Priory of St Helen. Often described as a nunnery with a secular church attached, the Parish Church was in fact the earlier building, put up in the 12th Century, and the nunnery was founded only in 1204-16, with the Nuns Quire adjacent to the Parish Church nave. On the dissolution of the Priory in 1538, the central wall was removed and the Parish Church remains, but bigger. And big it is, for a City Church, at 120ft long and 50ft wide in the now doubled nave though the Nuns Quire is now also called the North Nave. The walls are mostly 12th and 13th Century, the supporting arches mostly 15th and 16th Century, and on this page with its predominantly sculptural concerns, we need only note further that the Church has continued to be repaired and refurbished, and added to, with two restorations in Victorian times and further changes more recently. Despite everything, to stand in the North Nave, the old Nuns Quire, is to experience an essentially complete Benedictine church of the 13th Century. It is a privilege to visit it.

St Helen Bishopsgate, frontage with yard.

St Helen Bishopsgate, frontage with yard.

A couple of words on the exterior we see from the outside the two parallel naves, long, broad and low walls it feels much higher within the Church than it looks from outside medieval and evocative, with the entrance facing onto the surviving courtyard and once surrounded with picturesque buildings (see engraving below). There is no ancient tower, but a small cupola over the west front, which is 18th Century.

St Helen Bishopsgate has an outstanding series of monuments, including over a dozen really grand ones from an early period, and 50-odd smaller ones, mostly later, with a broad range of 18th and 19th Century types. The collection includes both those which were originally erected in the Church, and those brought here when nearby St Martin's Outwich was demolished in 1877. We start with the early grand tombs.

View of St Helen Bishopsgate before modern buildings introduced.

View of St Helen Bishopsgate before modern buildings introduced.

St Helen Bishopsgate now possesses four great monuments with figure sculpture where the subjects lie on their backs, recumbent, and we commence with these. They include the oldest alabaster monument in the Church, and we conveniently have one from each of the 14th, 15th, 16th and 17th Centuries.

Sir John de Oteswich, and wife Mary, 14th/15th Century.

Sir John de Oteswich, and wife Mary, 14th/15th Century.

The tomb of John de Oteswich consists of two recumbent figures in alabaster, of him and his wife, Mary (the name given on the modern inscription), now on a solid stone block cut in the 19th Century. John Oteswich (or John de Oteswich), with several others of his family, founded or were proprietors of the church of St Martin s Outwich, which took the family name. That church stood at the corner of Bishopsgate and Threadneedle Street, survived the Great Fire of London as an old Gothic structure of the meaner style , was rebuilt at the end of the 18th Century with an oval interior, only to be demolished in 1874. The figures were brought, along with other monuments, to St Helen Bishopsgate, and of the grand monuments, this is the oldest, dating from the late 14th or early 15th Century. Strype, the historian who updated Stow s 1600 Survey of London, refers to John Oteswich and his Wife, under a fair Monument , suggesting a canopy, and the inscription indicated that Martin de Oteswich, Nicholas de Oteswich, and John Oteswich, son of William, thus all the four Founders of the Church, were buried there.

Heads of John and Mary de Oteswich.

Heads of John and Mary de Oteswich.

The ancient medieval figures are dressed in long robes down to their feet, the drapery having straight folds down the line of the figure, as if the effects of gravity when they were standing up the effect is of a hypnotic calmness, and the lines especially of Mary de Oteswich s sleeve are perfect. Her face is rounded of cheek, with rather shallow depressions for the eyes, and a thin nose above a small mouth. She wears a hood, and her long hair can be seen down the sides of her face. John de Oteswich appears older, a patriarch, with more sunken eyes, more prominent cheekbones, larger though still thin nose, and a shortish beard and whiskers. His hair is wavy and curled below the ear height. Both figures are shown in an attitude of prayer, her hands clasped together, his touching at the fingertips. Of ornament, they wear little: a line of beads or tiny buttons on his chest, and a bag, perhaps for money, held shut by two tasselled drawstrings at his waist; an embroidered edge to the top of Mary de Oteswich s top under the cloak, and floral buttons below. He also wears a long sword in a scabbard, reducing the rather saintly aspect he otherwise presents. They both lie on small pillows, held at the upper corners by figures of clerics or angels, four in all, looking upwards and most medieval in spirit. At their feet are the small animals sometimes found on such monuments: a pair of small piglike dogs for her, a lion with droopy mane for him, animals of serious aspect and character.

The monument to Sir John Crosby, d.1476, of Crosby Hall, and his wife Agnes [Agnetis], d.1466, is a splendid couple of recumbent statues, lying upon a great altar tomb, which unlike that of John Oteswich, would seem to be original: it has three panels on each side, with shields of arms (see engraving below). The railings around the monument are relatively modern additions. Sir John hair is cut short and to equal length around his temples, and looks ungainly to modern eyes; beneath this, we see a slightly furrowed brow, and long, stern face, as of later middle age. He too wears a cloak, covering his shoulders, upper chest and lying underneath him. But his main garb is his full plate armour, closely fitted to the body to emphasise his supple frame, most particularly in the lower legs, which are raised off the base to rest upon a seated catlike beast.

Sir John Crosby and wife Agnes, later 15th Century, and details of portrait sculpture and heraldic beast.

While Sir John rests his head upon some rolled pillow, Agnes Crosby s head is supported by a cushion, held by two small angels. She has a smoother face, somewhat younger than her husband, and wears a tight-fitting shirt emphasising her slender arms and narrow waist, above a full skirt. Her cloak, on which she lies, covers part of her elbows. Her hair is covered with one of those splendid medieval headpieces familiar from Books of Hours, and around her neck is a lightly carved necklace, broad, decorated with flowers, and a central hanging. Around her hands, clasped in prayer, is some sort of binding. Her feet are covered entirely over by the ends of her skirt, and while the direction of gravity is conventionally along her body, as if she were standing up, the folds on her feet hang vertically down; there are two small dogs at the base, one of which has lost its head. Overall, a group of great beauty and skilful work by the sculptor in composition and detail.

A grand monument indeed the recumbent effigy of Sir William Pickering, in full armour, lies on a large altar tomb within iron railings. Above is a double arched canopy on six Corinthian columns, and on top of that, a central structure bears a painted shield of arms within an open circlet, resting upon two small sphinxes.

Monument to Sir William Pickering, d.1574, perhaps by Cornelius Cure.

The figure of Sir William is finely carved: his face framed with short, wavy hair and carefully delineated head, large domed forehead, small nose and strong cheekbones, and has the eyes cast heavenwards. His finely veined hands, long of fingernail and a little large of knuckle, are clasped in prayer. His armour is extremely fine, carved in low relief with leaves and berries, on straps and along the arms and the lower tunic. He has a ruff at the neck above a high collar, and smaller ruffs around the wrists. His armoured legs, below the puffed Elizabethan waist, carry on the leafy carving, and the contours of the calf and ankles are nicely captured. He lies on a rush mat, rolled over at the top to make a pillow, which rests on the heavy altar tomb beneath, made of blocks of marble and dark panels.

Gresham, Pickering and Judd monuments, mid-19th Century view.

Gresham, Pickering and Judd monuments, mid-19th Century view.

The pillars are of coloured marble, and gilt on the Corinthian capitals. The inner arches are filled with small coffers, carved flowers and stylised leaves within them, and above each arch is a small lion s head. The top of the canopy is flat, with ball finials on the corners, and curly strapwork in the middle of each long side. In the centre is a small casket on which, as noted, is the small coat of arms, knight s helm on top, curly Acanthus leaves around it, filling a circlet which itself is a piece of strapwork. The sphinxes on which this rests, clasped between their wings and with sidepieces resting on their heads, are charming creatures. They are crouched down on their lion back legs, but there is little else leonine about them, for behind, their rumps elongate into long curved tails doubled because there are separate tails on the other side which are twined together and bear fishy fins at the ends and above the legs. The body of each sphinx arches upwards, to give a feminine stomach, ribcage and breasts, albeit taut and muscular, but the residual shoulders bear wings, not arms. Above, the solid neck bears a head, looking large due to the lack of shoulders and the gilt headdress, but on this quintessentially Egyptian creature, the features are entirely Western something between Renaissance and Classical. Excellent things, spirited and characterful. [This website has a penchant for sphinxes: see this page.] The monument has been suggested as being by William Cure the Elder, and more recently to ascribed to the sculptor Cornelius Cure, his son, on the basis of comparison with another work by him to Lord Burghley, who was an executor to Pickering s will. Sir Nicholas Throkmorton in St Katherine Cree is ascribed to the same artist.

Details of the monument to Sir William Pickering.

An alabaster Elizabethan monument of the grandest scale, with the changed height of the floor leaving the structure partly beneath the current ground level, yet still rising up to the height of the Church gallery. As with a kneeler monument, we have two arches supporting an entablature, but in place of the usual couple of kneelers facing each other, we have two full size recumbent figures, painted, hands raised in prayer, heads to one side and their feet stretching well across the midpoint of the available space. To the left, under their feet, is a single kneeling, praying figure of a woman, at her prayer desk, to a much reduced scale. The figures of John Spencer and his wife are stiff, but as he wears armour, it is in the figure of his wife that we notice this particularly; as usual, we may also note that her long skirt shows a gravity towards her feet rather than vertically downwards. Sir John has some doublet over the front of his armour, and a broad ruff under his long beard; his wife s ruff is smaller. The best features of the statues are Sir John s legs, encased in armour, but showing the outline of the calves and feet quite naturalistically. The small figure of the kneeler, a youngish woman with wide ruff and hood, a daughter of the couple, wears the widest skirt imaginable, giving her a squat appearance.

Sir John Spencer, d.1608 perhaps by Nicholas Johnson

Sir John Spencer, d.1608 perhaps by Nicholas Johnson

We have mentioned the two arches above the figures, and in front of the outer pilasters are two great black marble obelisks, each crowned with a gilt ball and spike. Behind and above the figures on the backing of the arches are the inscriptions surrounded by carved ribbons, festoons, and fripperies. The inside of the arches themselves are reserved for the shields of arms and more carved ribbons, with coffering above. A further painted cartouche of arms, heart shaped, occupies the central spandrel, and the keystone of each arch bears a small winged cherub head. Then the entablature, more alabaster and narrow black panelling, and a shelf, on which sits a full strapwork structure. Thus a coat of arms with knight s helm and open-winged pigeon or other bird, with a mantelpiece-like surround, with delicate carvings of ribbons and small fruits on a central shaft, all gilt, and to each side, lesser open strapwork, and the respective shields of husband and wife at the corners, his with an eagle above, hers with the head of some camel-like beast. At the very top, above a final shelf, between two gilt balls are the memento mori a little winged skull and an hourglass. The figures lie on the usual altar tomb, more marble and alabaster, and this is sunk down below the present floor level of the Church. The monument was suggested by Mrs Esdaile, the early historian of British tomb sculpture, as being by Nicholas Johnson, on the basis of similarities with other works.

There are five altar tombs dating from the 16th and 17th Centuries, including an Easter Sepulchre, all grand enough, but of more architectural than sculptural interest, and they include one historic personage of great importance to London: Sir Thomas Gresham, founder of the City s Royal Exchange.

An altar tomb against the wall with back inset into or against the wall and a canopy roof structure above, a bit like an Easter Sepulchre (though we come to the actual Easter Sepulchre below). There are three panels containing quatrefoils on the front of the altar tomb, and three beautiful ogee (s-shaped) Gothic arches above, crocketed (toothed), and between these arches, many small blank trefoil headed windows. More carving on the cornice above, of alternate four and six-petalled flowers, and on top, a row of many diamond shaped flowers. At the back of the tomb, we see more stone panels where brasses once were emplaced. This architectural edifice is used as a sideboard for books and leaflets, yet here is the monument to Hugh Pemberton, d.1500, over half a millennium old, and surviving from vanished St Martin Outwich.

An Easter Sepulchre is a construction found in some English churches not elsewhere I think where during the Easter period the Church s crucifix and holy paraphernalia would be placed (remembering that the churches in question would have been Catholic then). Thus we have a sideboard-like base, an altar tomb really, but set into the wall, with a frame above it, with outer pilasters, and a central recessed area set right into the wall, with Gothic tracery, and above that, the entablature and something of a canopy. There were once brasses at the back of the recess, which according to the will of Johane Alfrey, were intended as herself as a kneeling, praying gentlewoman, contemplating the Holy Trinity and Saints Catherine and Helen. In the 18th Century there were still two coats of arms there, which proved the Easter Sepulchre was the one in Johane Alfrey s will, but all are gone now. The monument also acts as a squint, so that nuns behind the wall could look in and see the service, for the the panels on the base each form a narrow open window. The sculptural adornment, some repeating small pattern above the recess and perhaps crocketing on top, is much worn, but still, it is an unusual survival of an early 16th Century church feature.

Jonane Alfrey's Easter Sepulchre with Sir Thomas Gresham's altar tomb, and detail.

The monument to Sir Thomas Gresham is a great altar tomb raised on a step. Upon its polished top is his name and date of his burial and nothing more. This top slab and the lower pedestal are somewhat protruding from the sides of the monument, which are in alabaster or marble carved all over with fluting, repeating designs of quatrefoil flowers of different sizes, and in the centre of each side, a device centred on a shield of arms. On the long face and the short one which face out of the corner in to the body of the Church are coats of arms with knight s helms above, similar but not identical. On top of each knight s helm is Gresham s symbol of the grasshopper (really rather rare in sculpture), and all around, scrolly acanthus leaves, beautifully carved, with low relief strapwork behind.

The two sides towards the walls differ from each other. On the short side is an oval shield incorporating three stag heads (it is the arms of Fernely), very medieval in style (see this page for more stag and deer sculpture); the whole being surrounded by strapwork and a variety of fruits grapes, a split pomegranate, apple, what seems to be a segmented gourd and so forth. The long side has a similar shield with stag heads, more open strapwork with scrolls, more nuts and berries than fruit, and two supporters in the form of nude cherubs, a bit battered, holding downturned torches signifying the extinction of life. Many fine details.

Sir Julius Caesar Adelmare died in the same year as Sir Thomas Gresham. This plain altar tomb, with slightly projecting pilasters at the corners, raised on a moulded base, has as its only ornament the inscriptions and shield of arms in white marble attached to the heavy black slab covering the monument, a shame, as it is known to be by the important early sculptor Nicholas Stone, for he records it in his surviving notebook. With a lengthy Latin inscription, and the coat of arms including stylised flowers, and the only significant bit of carving, a fish in the sea, with lower tusks, scaly body, and fins; it has been described as a dolphin, but the scales belie this.

Detail of Sir Julius Caesar Adelmare tomb, by Nicholas Stone the Elder.

Detail of Sir Julius Caesar Adelmare tomb, by Nicholas Stone the Elder.

Dame Abigail Lawrence, d.1682, wife of Sir John Lawrence, the tender Mother of ten Children // the nine first being all daughters // shee suckled at her owne breasts // they all lived to be of age // her last a son died an Infant // Shee lived a married wife thirty nine years // three and twenty whereof // Shee was an Exemplary matron of this Cittie . The altar tomb is carved as if covered in front with a shroud, with the inscription on a tall plinth upon it, with carved curly side pieces and large hanging buds. Upon this is a smaller block, gadrooned (corrugated) on top, on which stands a small lidded pot or urn.

A railed altar tomb of moderate size. It is nice that the railings are preserved, but it means we cannot see the artistic elements of the tomb properly. We see a tall, rather slender tomb, with oversized upper slab in pale marble. The corners of the sides have low relief carved decoration ribbons, crossed bones, skull, fruit, hourglass, a book; and each side has a panel with inscribed decoration, coat of arms, and knight s helm. On the side we see a pair of kneelers, male and female, he with hat, wide sleeves, and cape; she with a similar hat and a very broad ruff. Between them is a single female offspring, half size, with shield of arms above. Unlike a sculpture, which would be in profile with the two figures facing one another, or looking straight forward, here we have all three figures in three-quarters view, and angled towards towards the viewer s left. There are inscriptions in English and Latin, to William Kerwin (sic) himself, of this Cittie of London, Freemason (d.1594), his wife Magdalen Kirwin, d.1592, by Whome He had issue III sonnes and II daughters , and one of those sons, Beimin [Banjamin] Kirwin, d.1621. The monument has been tentatively suggested as being by the sculptor Epiphanius Evesham by Mrs Esdaile, the historian of tomb sculpture who attributed the monument to Sir John Spencer above.

Elizabethan Kneeler monuments, sometimes referred to loosely as Tudor monuments, are so called for the kneeling, praying statues of the deceased - there is a whole page about them here. They are often painted, sometimes rather unflatteringly to the sitter in both carving and colour, or may be left in the natural alabaster colour, and if a couple, they generally kneel facing each other across little prayer desks, with their children behind them, neatly divided by sex. The men wear armour if knights, or rich robes if not, and usually have the familiar Elizabethan collars. The women often wear head coverings, and robes or skirts which are usually voluminous, presenting a typically shapeless female figure. Both men and women sit on little cushions with tassels at the corners, and normally the whole ensemble is within one or two arches, with some construction above and below. St Helen Bishopsgate has four such kneeler monuments, and the huge monument to John Spencer noted above has a small kneeler as well as the recumbent figures, and is of the same overall style and period. The St Helen kneelers are typical of the breed.

Kneeler monuments: Judd, and figures from Staper and Bonde monuments.

Sir Andrew Judd, d.1558, founder of the Free Grammar School at Tunbridge, with a short effusive epitaph, dating from later than the monument itself, noting his three wives: Mary, by whom he had four sons and one daughter [a mayde ], Annys [Agnes rather than Ann], with whom he had no offspring, and Dame Mary, who produced a daughter. This kneeler monument is not so large (see mid-19th Century engraving further up page), with an arch under which Sir Andrew kneels with his four sons ranged behind him, facing a second arch under which are his womenfolk: but there is a puzzle here as there are only two females, who by their age could be two of the wives, with one wife missing perhaps Ann, as there were no children of that union. But this would be unusual, as the daughters are absent too. It is more likely that we see the last wife, Dame Mary, and her daughter, Alice, who was his heiress it seems that Dame Mary survived her husband, and we can readily imagine that she may have felt that there was no great necessity to record the two earlier wives with their own statues.

Sir Andrew wears full armour under a light cloak, as befits a knight; his hair is rather medieval, he is beardless above a thin ruff, and he wears a chain of office. As usual, the figure is kneeling in front of a prayer desk, here covered with a cloth with border decorations and a fringe. His sons behind him are wearing civilian clothes: long cloaks with upturned collars for the two grown sons, tunics and outer sleeved shirts for the two young children. As generally the case with such monuments, the paintwork means something is likely lost in the surface quality of the sculpture, but the well studied folds of the drapery and the fine quality of some of the details of the faces the ears, noses and eyes show a skilful sculptor at work. Dame Mary and her daughter, if these attributions are correct, are rather grim of aspect, especially the former, with a leathery appearance. Both wear double layered head scarves, and have ruffs under the collars of their outer garments, but while the front kneeling figure has a long, hanging sleeve, she behind has a narrow sleeve and is less richly dressed. Fluted Corinthian pillars are at each side and in the centre, and the arches form small spandrels with these pillars, allowing for minor leafy sculptural decoration, and two flattened male heads in the keystone positions. Above, the coat of arms with knight s helm and surrounding acanthus leaf decorations lie within a large arched panel of its own; it seems likely there was something to the sides at one point, for compositional reasons if nothing else. At the base, the inscription forms two panels, one beneath each arch, and between these and at the edges are small panels with sculpture of fruits and berries; a further subsidiary base is beneath this. All in coloured and gilt alabaster.

William Bonde, d.1576, Alderman, sometime Shreve of London, a Marchant Adventurer, moste famous in his age for his greate adventures bothe by sea and lande . A coloured kneeler monument, again not so large. The kneeling figure of William Bonde is on a panel, with narrow prayer desk, facing his wife across a central pillar, who has a similar prayer desk, and is in a similar panel. He wears a long robe covering his body; there is little or nothing in the drapery to indicate the line of the legs underneath. Behind him are ranged his sons, seven in all, and in their case, for the nearest figures, both sleeves and folds indicate the limbs more fully. His wife, in hood or cap, robe, and with a thin ruff his is thinner is shown in middle age, and behind her is the single daughter of the couple, of somewhat greater size than the sons to give some balancing weight to that side of the composition (see picture above, right). On each panel, behind the head of the couple, are coats of arms, and carved ribbons. As well as the central pillar, there are two similar outer pillars, with black shafts and Corinthian capitals, supporting an entablature rather than arches, which are perhaps more usual on Elizabethan kneeler monuments, though the flat top is by no means uncommon. Above is a pediment, broken at the top with a large carved shield of arms in a circle, with knight s helm and scrolly feathers. On top of the knight s helm is a small lion, and lion heads are on the top and bottom support of the circle (if you like lion head sculpture, see this page). The right and left sides of this circle contain grotesque faces of satyrs carved in relief, each with a ball in the mouth (more satyr sculpture on this page). The base of the monument contains receding panels with the various inscriptions upon them; quotations are above the figure panels. A very typical example of a kneeler monument. The relevant volume of Pevsner s architectural guides, as revised after his death, suggests Garat Johnson the Elder may have been the sculptor.

John Robinson and Christian Robinson, another kneeler monument, this time unpainted, and with the arches hardly recessed. The kneeling figures, rather modest in size, show the deceased and his wife kneeling facing each other over a rather short prayer table, not really that close to one another but appearing so because although the arches descend between them to a pillar, this is a recessed pilaster rather than projecting forward, so the couple appear able to gaze directly towards each other. Behind them are rank after rank of offspring, separated by sex as usual. There seem to be eight sons, and seven daughters, rather battered unfortunately, and with the sons in front carved as closely identical in posture and drapery to their father as possible. Similarly, the daughters are reflections of their mother, though with less dumpy figures. Even accounting for the poor state of preservation, the repeating drapery suggests that this was not carved particularly imaginatively. The rest of the monument is in coloured alabaster: two Corinthian pillars at the sides, arches above filled with low relief shields of arms and carved ribbons, spandrels with stylised leafy scrolls, and little winged cherub heads above each arch (more cherubs are on this page). Above all this is an entablature, and then a wide base on which is a carved shield of arms within a circlet of strapwork; likely this continued outward and downward and some has been lost. At the base, the inscribed panels curve downwards and towards the wall, and beneath is further strapwork and a lozenge in a circle with more ribbons.

A kneeler monument, with the figures of Richard Staper, d.1608, and his wife it must be her, though she is not mentioned in the monument inscription, and their offspring: four daughters ranged behind the mother, and five sons behind the father (see kneeler monuments picture above, centre). He was the greatest merchant in his tyme, the cheifest Actor in Discoveri, of the trades of Turkey,and East India... . Although the name of his wife is not mentioned, the monument casts her as slightly larger than her husband, both in girth and height. Both wear large ruffs, hers the larger, which is conventional, and both kneel on tasselled cushions and have their hands held in prayer, also conventional, though their almost touching hands above the small prayer desk is less usual. There is fine drapery to both figures, and the drapes of the son in the foreground behind Richard Staper are similar but not identical to his father. The daughters, each with the same curious headpiece as their mother, also wear similar costume, though with wrinkly sleeves rather than the fluted one with shoulder decorated with flowers seen on the mother. The two figure groups are under the normal separate arches, descending part way at the centre and with receding central pilaster above and behind the prayer desk. To the outside are two full Corinthian pillars, and within the arches and around them in the spandrels are a mix of low relief carvings of flowers, leaves, ribbons and two coats of arms, now blank; a small cherubic head is at each keystone. Above, an entablature supports a complete superstructure of open strapwork, with central circlet enclosing the coat of arms, here with a lion seated upon the knight s helm, and lower, flat-cut outer portions, each with a grotesque lion head in relief upon it. At the very top is the damaged hulk of a warship with guns extended (see picture below, you will need to click to enlarge). The inscriptions are at the base, under an ornamented shelf, on two panels separated by small panels and corbels carved with flowers.

The warship and coat of arms of Richard Staper.

The warship and coat of arms of Richard Staper.

To these recumbent figures, altar tombs and recumbent figures, we should add three more monuments of massive size, before passing on to their lesser brethren.

The monument includes an interesting carved panel showing Martin Bond in full armour seated in his tent, resting one elbow on a sideboard on which his helm and one gauntlet lie: we have the sense of a weary hero resting from his labours. His sword rests point down in front of him, and a further sword, shield with arms and pike are behind and above him, on the further wall of the tent. On each side of the tent are armed soldiers, with flamboyant hats, long hair and beards, carrying muskets and wearing tunic, baggy breeches and tall boots. Behind the soldier on the left side as we look at the monument, an attendant holds a horse, waiting for his master. In the background, carved in low relief, we see further tents, implying some army. The whole in alabaster. The panel has on each side a detached Corinthian column, with a grey marble shaft, and pink alabaster behind; below are curvy supports, and the commemorative panel is between, with outer hangings of carved fruit and flowers; at the very base is a small coat of arms with scrolly surround which would seem to be a stylised representation of a pair of guns. At the top is a curved pediment, broken in the centre to admit a coat of arms with knight s helm, both very small, and lots of scrolling around. The inscription notes that as well as being Captain at Tilbury, he was Cheife Captaine of ye Trained Bandes of this Citty , a Merchant Adventurer, and a Haberdasher. His Pyety, Prudence, Courage and Charity have left behind him a Never Dying Monument . A short Latin inscription follows, and a note that William Bond put up the monument presumably the William Bond[e] we have met amongst the kneelers. The Pevsner volume suggests the monument could be the work of the important sculptor Thomas Stanton.

Rachel Chambrelan, d.1687. A large mural monument. The inscribed panel is of normal size, but is surrounded by various adornments to give a much larger composition. The panel, then, is the projecting centre of a broad slab, with two naked cherubs standing at the sides: one weeping and holding a handkerchief to his face, the other holding a flaming torch and dramatically gesturing skywards. Above, an entablature and shelf, then a sort of urn raised on a series of bases, with somewhat damaged festoons of leaves and flowers to each side, ambitiously carved. To each side is a smaller plinth with a flaming lamp in the shape of a stylised shell or boat, very appealing. Underneath the panel is a wavy (gadrooned) projecting shelf, which recedes at its base to a panel with a second inscription, with at the sides small winged cherub heads and wreaths. At the base, a sort of apron made by a small shield of arms over two crossed palm fronds, with hanging drapes caught up at the sides in knots with drop folds. Another pair of winged cherub heads are underneath, and below these, twining trails of carved flowers. Really rather interesting sculpturally.

Our only grand 18th Century monument, and perhaps we should have placed it among the altar tombs, as this is what the base of the monument is. Walter Bernard, d.1746, Alderman and late Sheriff of this City; in both which Stations He acted to the General Satisfaction of his Fellow Citizens . A grand monument of coloured marbles and many architectural features. The base, as said, is an altar tomb or tomb chest, placed against the wall, with central section forward, bearing the inscription; the receding sides have upon them free-standing flaming pots. The central part then rises as short stage carved in corrugated fashion, above which is a tall panel of white-streaked dark marble which has upon it a tall slate-coloured obelisk, bearing a coat of arms in a cartouche with the usual knight s helm, Acanthus leaf surround, and crowned with a bear. All finely carved. All of this is framed with two pillars of brecciated marble with Ionic capitals bearing a shelf. On top of that, a central, flaming pot is attached to the wall, and flaming shells are on the sides above the pillars. The variety of marbles and free-standing pots of this many-layered monument make it a grand and ostentatious demonstration of wealth.

So these are the grand tombs of St Helen s Bishopsgate, and we now move on to the smaller monuments, which still include some splendid things, including some of sculptural interest.

The bulk of these monuments have already been covered, but there are another half a dozen mural (panel) monuments which we note here:

The 18th Century monuments in the Church introduce us to the Cartouche, the shield-shaped or violin-shaped panel with sculptural rather than architectural Baroque surround, which is perhaps the most beautiful type of mural monument. Cartouches appear in the late 17th Century, but had their heyday in the first half of the 18th Century, and the three examples at St Helen s Bishopsgate date from the earlier part of that period: Henry White and Gervash Reresby from the 1700s, and Thomas Clutterbuck from 1714 (mini-cartouches just for the coats of arms of a monument are much more common). Towards the end of the century we come across the obelisk monument, starting with Peter Gaussen, d.1788, the best of the five in the Church, but the group as a whole make an interesting collection because each of them has a different shaped obelisk. The point of the obelisk, forgiving the pun, is that it is an Egyptian symbol evoking death and rebirth. However, we start the century with an oddity:

Thomas Langham, d.1700, and detail.

Thomas Langham, d.1700, and detail.

Cartouches, early 18th Century: White, Reresby and Clutterbuck.

Peter Gaussen, d.1788, obelisk monument with fugure sculpture.

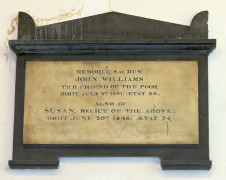

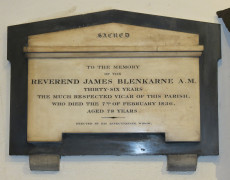

The majority of 19th Century church monuments are from the early decades, the numerous white marble on a black backing type, with the design frequently in the form of a tomb-chest end, with upper shelf, little legs below, and perhaps a lid above, or a small pediment with ears (acroteria). The monuments to James Hester, John Williams and the Revd. James Blenkarne epitomise the type in St Helen s. The sides of the panel can angle outwards, giving a casket end, as in the memorial slabs to Barbara Gould Simpson and Samuel Winter, for example. Often these tablets are without sculptural adornment, but we may have a high relief pot or urn on top, typically draped, as with Edward Edwards, Revd. John Rose and Henry Ward. The Jane Blenkarne monument has a draped casket on top of a tomb chest end design, all in pale marble, unusual in St Helen s in having a visible signature of the sculptor, William Behnes. Three out of the five obelisk monuments are among the 19th Century monuments, rather late for such things.

Obelisk monuments, later variations: Kuhff, Miles, Thompson and Ellis.

Typical black and white panels from the 1830s: Williams, Baumer and Winter.

Revd. James Blenkarne, and wife Jane, and relations, the latter by William Behnes.

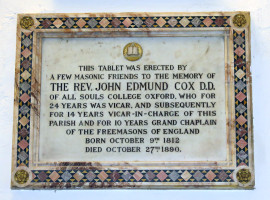

The reason to break at mid-19th Century is because the couple of examples we happen to have in St Helen s Bishopsgate from the late 19th Century belong with the Arts and Crafts revival style which reached its peak at around 1900 or shortly after. This is particularly so with the multicoloured panel to the Revd. John Edmund Cox.

Revival of the coloured monument: Revd. John Edmund Cox, d.1890..

Revival of the coloured monument: Revd. John Edmund Cox, d.1890..

To avoid this page being unduly long, we touch only briefly on the brasses, noting there is a good collection of standing figures, male and female, dating from the 15th and 16th Centuries. They include Nicholas Wotton, d.1482, from the church of St Martin Outwich, where he was the rector, and a noble knight in armour in the person of John Leventhorp, d.1510. Also notable are Robert Rochester, d.1514, and a 1530s figure of a lady in a long robe with two tall heraldic lions inscribed upon the flanks. Best of all is the slender, supple figure of Margaret Wylliams, shown with her husband Thomas Wylliams, d.1495, which in a few elegant lines shows the curvy silhouette of a medieval beauty.

There are also a number of modern brasses, including Alexander Macdougall, d.1835, William Jones, d.1882, Charles Matthew Clode, d.1893, Revd. John Alfred Lumb Airey, Rector, d.1900, James Fletcher, d.1907, and Percy Richard Venner, d.1932, and Maud Edith Venner, d.1966. These serve to show the conventional type of such brasses, which involves typically black letter or capitalised text, with the initials in red, some sort of inscribed border which can bear a repeating design, and a feature made of the corners. The panel to James Fletcher includes the arch of a Gothic window in the design.

With many thanks to the church authorities at St Helen Bishopsgate for permission to use photos from inside the Church, and in particular to Mike Burden there; their website is at http://www.st-helens.org.uk/.

Down St Mary Axe to to St Andrew Undershaft // South to St Olave Hart St // Or to the tower of All Hallows Staining // or south east to St Katharine Cree // South west to St Mary Woolnoth // Eastward to St Botolph Aldgate

City Churches // Introduction to Church Monuments // London sculpture

Visits to this page from 6 December 2014: 5,014 since 1 December 2022