) and deaths-heads

(bat winged skulls), in a Baroque alternative to the more architectural rectangular monuments.

Also we have two panels carved as a hanging drape with a fringe at the bottom, a widespread but always rather unusual type.

From the late 18th and early 19th Century there are three obelisk monuments, often called pyramid monuments,

where above the main panel there rises a tall obelisk, typically with some relief sculpture of a pot or coat of arms upon it.

St Andrew Undershaft has just a couple of the grand Classical panel of the 17th/18th Centuries,

but a fair selection of the simpler panels of the early 19th Century, which are often styled to look like the end of a tomb chest,

thus a panel with a lid above a projecting shelf, rather like a small, rimless pediment, perhaps with ears

or acroteria at its sides, and with the bottom of the panel cut to give two feet. Finally, from the early 20th Century

are two of memorials reviving the use of coloured alabaster and marble, which had disappeared almost entirely around 1800,

in an Arts and Crafts style, and then from 1983, a modern brass in the shape of a bell.

16th Century monuments

Nicholas Levison, d.1534, and wife - and children.

Nicholas Levison, d.1534, and wife - and children.

- Nicholas Levison, d.1534, Sheriff of London, and wife, brass still in its matrix, a great stone slab,

which doubtless once lay upon the floor or the top of some chest tomb. The kneeling figures of the couple face each other

from a close distance, each wearing long, enfolding robes, the folds and angles confidently delineated. His face is not aged,

and he is clean shaven, with almost straight combed hair over his ears. His hands are in an attitude of praying.

His wife s face is rather worn, but from her slender figure we can judge her as a relatively youthful figure,

her hands raised at her chest as if beseeching, but not praying. Behind and aboe them are three coats of arms,

but the chief feature of the monument is the host of offspring, male and female, ranged behind father and mother.

Apparently there are 10 boys and 8 girls, though I was unable to quite make the boys add up. Charming,

and a splendid piece overall.

Sir Thomas Ofley, d.1582, and wife Joanna, d.1578.

Sir Thomas Ofley, d.1582, and wife Joanna, d.1578.

- Sir Thomas Ofley, Kt, of Stafford, d.1582, Lord Mayor in 1556, and his wife Joanna, d.1578,

with a rhyming inscription, beginning Intombed in this monument here rests a worthy wight, // president,

Alderman, somtyme maior, Sr Thomas Ofley knight, , and noting his long marriage, and three sons, of whom one, Henry,

survived him. A little inscription higher up has a further rhyme: By me a lykelihoode heholde, // how mortal man shal torn

to mold, // when all his pompie and glorivayne // shal change to dust and earth agayne // such is his great incertaintye //

a flower and type of vanitye . This is a kneeler monument in the grand style. Sir Thomas and his wife are presented as two

full statues each in their own recess under a Roman arch, facing each other, each with a prayer desk, and the centre descending

to a thick pillar above a short plinth on which are shown in high relief their three sons, in miniature size.

Above the pillar, between the arches, is a circular recess with a skull within it. To the sides, Corinthian pillars

support an entablature and upper shelf, which bears a coat of arms within a circle, two smaller coats of arms,

and reclining cherubs at the sides, each resting an arm on a skull. Beneath the main figures, the carving is as of a balustrade,

with the inscription on the central portion, and beneath a lower shelf the monument recedes to the wall,

bearing three larger shields of arms. In pale and dark marble, with painted figures and arms, it makes a grand sight.

The figure of Sir Thomas is shown as a dignified man with long, grey hair, ruff, and flowing robes lined with fur;

his wife wears a skull cap, and her robes include an enormous hanging sleeve in fur to indicate her wealth. The sculptor

of this monument has been given as Johnson by various writers, which is to say Gerard (Garat) Johnson the elder or one of

his relatives in the same workshop; a more recent attribution is to Cornelius Cure. There is apparently another wall monument

with figure of Dorothy Offley, d.1610, but I did not see it.

- Simon Burton, d.1593, Citizen and Waxchadler [wax chandler] of London, Master of that City

Livery Company, benefactor to the poor, a Governor of St Thomas s Hospital etc.

Brass set with a stone border with repeating pattern and flowers at the corners. The brass itself shows the kneeling figure

of the deceased, faced across a prayer table by his two wives, Elizabeth and Ann, with the younger figure in front of the elder.

The inscription says that Burton had issue by Elizabeth 1 Sonn and III Daughters , and we see their pictures underneath

the parents. However, the daughter in front resembles the first wife, Elizabeth, while the rear two resemble the second wife,

Ann, so they may be hers. One daughter was Dame Alice Bynge, whose monument we will meet below.

All the figures are nicely proportioned, and it is interesting to see how similarly posed and garbed

the figures on the brass are to the typical kneeler monuments of a similar and slightly later period,

including in St Andrew Undershaft, see below.

17th Century Monuments

John Stow, d.1605, perhaps by Nicholas Johnson.

- John Stow, d.1605, a great hero of these pages and rightly of everyone, who wrote the Survey of London,

first published in 1598, describing all the churches and thoroughfares, and including lively stories of the neighbourhoods.

This account, later updated and annotated by Strype, rests as one of the most important historical records of London we have.

The statue of Stow is shown facing the viewer, seated at his writing desk, hands upon his book, with a fresh quill placed

in his right hand annually. He is middle aged, high of forehead ,calm of aspect, with short hair, beard, and moustache,

wearing a ruff and long, scholarly robes. He is within a rectangular recess, the pilasters to the sides supporting a

low entablature and above this, a coat of arms of heraldic lion and tent within a circle of strapwork.

The entire surface of the side pilasters is covered with low relief carving: ribbons and tassels, crossed bones,

a flaming pot depending from cords, a winged skull, lion s heads, and so on. The whole in bright orangey alabaster and marble,

or at least it looks like it, but has been described as being of burnt clay or terra cotta. It used to be painted.

Mrs Esdaile, pioneer of church monuments, attributed the work to the sculptor Nicholas Johnson, but more recent studies

have rather doubted this.

- Margery Turner, d.1607, her first husband Isaack Sutton, d.1589, Citizen and Goldsmith

of London. A darkened marble or alabaster panel, with wide frame, the side pilasters carved with a variety of memento mori

and other decoration: hourglass, flaming torch, fruits, ribbons, skull and crossbones. Top and bottom shelf, and at the top,

a coat of arms in a characteristic strapwork surround; two smaller shields of arms at the sides. At the base, an apron

between two brackets, and more low relief carving. This monument is extremely characteristic of monuments of this period,

and abounds with lively and somewhat macabre sculptural decoration, including four grotesque heads more or less at the corners

of the frame.

Early 17th Classical panels: Turner and Warner monuments.

Early 17th Classical panels: Turner and Warner monuments.

- Alyce Bynge, d.1616, who had three husbands, all bachelers & stacioners . A kneeler monument,

rather modest in size, with the kneeling statue of the deceased lady within a round headed arch, with a

proportionally larger than usual prayer desk, and no sign of the husbands or offspring (see picture at top of page, left). The spandrels of the arch are decorated

in low relief with exotic flowers, and to the side are pilasters without capitals, carved in relief with familiar motifs: a skull,

book, flowers, ribbons, and hourglass. At the top, a pediment one rim is lost contains a shield of arms and a ribbon;

at the base under the inscription is a shallow apron with a central grinning skull; to the sides are modest brackets.

The figure shows her in black dress, with a cowl over her hair and shoulders, wearing also a large, rich ruff; her face,

overlarge to her body, is old and typically unflattering in appearance. Overall, really rather a good example of

the earlier period of kneeler monuments, more grim and gloomy than those that came a decade or so later.

- Edward Warner, d.1628, with a long inscription that he was second Sonne of Francis Warner of Parham

in the County of Suffolke Esquire by Mary his second wife daughter and Coheire of Sir Edmunde Rowse of the said County Knight

which Francis Warner was truly and lineally descended from the auntient [ancient] and Generous Family of the Warners

who possessed a place of theire owne name at Warners Hall in great Waltham in the Countie of Essex , continuing that his nephew,

Francis Warner was made his principal heir and out of duty and affection to the memory of his deere uncle hath dedicated

this Monument . A grand wall panel with a frame bearing six small shields, outer Corinthian pillars,

with recessed pilasters behind and to the sides, a narrow entablature bearing a central cherubic head, and above,

a broken, curved pediment enclosing a complex shield of arms, painted, surrounded by drapery rather than the more usual feathers

or acanthus, surmounted by a knight s helm bearing a small bust of a whiskered, bearded man in a hat.

At the base, a narrow panel notes Warner s two wives, Mary and Margaret, and is surrounded by a pair

of brackets bearing painted shields, and with carved scrolls, garlands and two small cherubic heads below this.

Sir Hugh Hamersley, d.1636, a grand kneeler monument.

Sir Hugh Hamersley, d.1636, a grand kneeler monument.

- Sir Hugh Hamersley, d.1636, monument erected in 1637, and holder of many honours, including being

Lord Mayor of London in 1627. A grand kneeler monument, extremely bulky. The two principal statues, Sir Hugh in front,

his wife behind, kneel within a single recess, above which is a canopy with hangings

rather unfortunately composed in that the hanging drapery rather obscures Sir Hugh s face, so the main feature appears

to be his stiffly-forward jutting beard. His face, so far as we can see it, is tilted back, with prominent forehead,

rather recessed nose, and he is either bald or wearing a skullcap. He is dressed in mail under a great cloak,

and kneels on the usual tasselled cushion. The female figure behind is typically bulky in skirts and mantel,

and has an oversized ruff which adds the triangular aspect of the figure as a whole, her smallish head at the apex.

And although we are used to monuments of this period making no attempt to flatter the sitter,

her aged, jowly face with sagging chin and grim, humourless expression takes this to an extreme.

To the sides are free-standing Composite pillars with black shafts and gilt capitals,

and outside of these are two standing statues, praying figures standing cross legged, with flamboyantly large boots,

wearing tunics, armour and helmets. Above the figures, a complex, Baroque swan necked pediment is broken at the top

to include a further architectural portico with broken pediment; on the front of this is a painted panel with arms,

and the upper pediment presumably would have once had some central device, perhaps a shield with knight s helm, now lost.

What does survive to the sides, though, are seated statues, one male, one female, wearing armour,

togas and carrying gilt oval shields. (The figures have been described as two females,

but this is belied by the masculine figure and moustache of the one.) The inscribed panel is under the figures on an apron

flanked by solid brackets, with architectural mouldings, and at the base is a small central device, rather scrolly,

with a low relief face of some grotesque feline - a picture is at the top of the page, third from left. Monuments do not come much grander than this.

The sculpture has been ascribed to Thomas Madden by a 19th Century authority, Peter Cunningham,

but the evidence for this is unknown and this sculptor is not known by other works.

- Antonius Abdalus [Anthony Abdy], d.1640 and wife Abigail, with a long Latin inscription

within a narrow black border, with outer scrolly sides, and carvings above and below.

Above, a curved pediment bearing three carved cherubic heads, rather overpowered by two larger cherubs standing upon

and in front of it, supporting a central shield of arms, painted, with heavy surround of scrolling, knight s helm and feathers.

At the base a scrolly apron bearing another coat of arms. It is by Henry Boughton, an assistant to the eminent sculptor

Edward Marshall. A few other works, outside London, have been tentatively ascribed to Boughton, none firmly.

The monument as a whole looks top and bottom heavy, and I wonder if there may have been some backing, and perhaps outer pillars

to give some more visually satisfying support to the upper part.

- Sir Christopher Clitherow, d.1642, Lord Mayor of London for 1635, Governor of the East India Company etc,

and second wife Dame Mary Clitherow, d.1645, (his first wife being called Katherine) and various offspring,

including son James Clitherow, whose second wife Mary and daughter of the same name, both d.1662, are also commemorated.

Panel of alabaster with broad frame of carved scrolls, a winged cherub head, and cascading buds and flowers;

a shield of arms with knight s helm is above. Sir Christopher gave some of the stained glass to St Andrew s Undershaft.

- Bridget Clitherow, d.1681, daughter of Christopher Clitherow, Lord Mayor of London,

alabaster panel with side pilasters, recessed, and with Corinthian capitals and curled bases.

Above is a black, plain entablature, then a curved or segmented pediment with some curvy decoration,

and a central tiny vessel which looks to have been the base of some larger thing, perhaps a circlet with coat of arms

in the centre. The base consists of an apron with relief carvings of a shield of arms and flowers.

- Johannes Jeffreys, d.1688, large cartouche with much foliage at the sides, of a springy palm-leaf type

which gives opportunity for a rather open, three dimensional frame to the central panel, and incorporating four cherubic heads,

coat of arms at the top with the usual knight s helm and crossed oak twig and flower (daffodil?) upon it,

and at the base a pair of winged skulls, entwined together in a rather disturbing group. Another monument with excellent carving.

Charles Thorold, d.1691, effective use of carved drapery.

Charles Thorold, d.1691, effective use of carved drapery.

- Charles Thorold, d.1691, with a note of his seven sons and seven daughters,

erected by his wife and son, Charles Thorold, Knight, with a codicil at the base that this son died in 1709.

A curved panel, with a semicircular top, with a border of drapery, gathered in the centre at the top,

hanging slightly and gathered by two cherubs at the sides, then with tasselled drapes hanging straight down to left and right,

and spilling over the shelf underneath. On top of the monument is a coat of arms with flourishes of feathers,

boldly carved and cut out. At the base, another coat of arms surrounded by leaves forms an apron with a corbel of massed leaves

at the bottom. A confidently carved and noble monument.

- Humphredus [Humphrey] Brooke, d.1693, with a Latin inscription,

on a fine cartouche with knotted drapery at the sides, scrolls and winged cherubic heads at the sides,

and a bat-winged skull at the base above a painted shield of arms. At the top, a knight s helm above a painted cartouche of arms.

- Mathias Datcheler, d.1699, and wife Mary, whose daughters Mary, Beatrix and Sarah

built the vault in the church in 1699. They, and various spouses, were buried there between 1726 and 1731,

and the inscription continues to list their bequests to the Church and gifts to the parish poor.

The long inscription is on a panel with rounded top, with surrounding frame, outer recessed curly pilasters,

a completely open rounded pediment on top, all made in a grey and white marble. On top of the pediment is a cartouche

bearing a painted coat of arms, and on the sides are a pair of winged cherubs, rotund and in attitudes of exaggerated mourning.

At the base, beneath a baroque apron is a corbel carved as a winged cherub head.

A slab in the churchyard to Datcheler is mentioned in texts but I have not seen it.

End of the 17th Century: Datchelor monument and cherubs.

18th Century Monuments

- Petrus van Sittart, [Peter Vansittart] d.1705, and others, with a long Latin inscription, on a truly splendid cartouche, with the inscription occupying less than a third of the total surface, so much ornament has been included. There are the usual knotted drapes at top left and right, with a mix of drapes and scrolls hanging to either side of the inscribed area, and resting upon two winged cherub heads. The base of this section of the monument has naturalistically carved flowers in low and high relief, extremely delicate in execution. Beneath, the drapes pull inwards to form a small hanging upon which are hanging leaves and berries, to each side of which is a rounded skull, each with a single visible batlike wing. The skulls have their lower jaws, which is not usually the case, but are lacking some teeth. The base is an elegant corbel made of two further adjacent winged cherub heads, above further clusters of berries and leaves, almost too delicate to be stone. At the top, directly above the text is the painted arms, encircled by a mini-cartouche with further drpery and ferny fronds,

and atop this is the usual knight s helm and leafy feathers, this one being topped by a small carved eagle.

This really is an excellent work and repays close study - click on the picture below left.

- Galfridus Jeffreys, [Geoffrey Jeffreys], d.1709, with a short Latin inscription,

carved as a hanging piece of fabric, held by two deeply carved knots at the top sides, with drop folds hanging down,

tassels at top and sides, a falling curve of fabric at the top, and under the fringed base, a cartouche enclosing a painted

coat of arms, flanked by foliage and with a pepperpot-shaped terminus at the base. Such carved hangings,

nearly always fringed are a widespread but never frequent type of memorial in the 18th Century.

18th Century cartouche monuments: Van Sittart, Sykes, Salter, and Jeffreys.

- Henry Sykes, d.1710, and wife Margarie Paynel, d.1694, with Latin inscription.

Another fine cartouche (see picture above, 2nd left), the inscription being on a turtle carapace shaped field, with a fringed hanging carved under it,

and at the sides, the upper knots and falling drapes over winged cherubic heads already seen in the Humphrey Brooke monument.

At the base is a larger winged cherubic head, and at the top, a painted cartouche of arms, and a carved bird, a goose in fact,

with a crown around its neck.

- John Jeffreys, d.1715, of Sheen, with a short Latin inscription, on another one of those monuments carved

as a hanging drape, with drop folds at the sides, two knots at the top, and festoon fold in between;

below the base of all this is a coat of arms, painted, and carved ornamental leaves, with a single central corbel at the base.

- Mrs Catharine Heames, d.1716, daughter of Sir Thomas Chambrelan, Knight,

sometime Governor of the East India Company, and various relatives, put up by her son, Thomas.

Panel with curly side pieces in place of pillars, adorned as well with carved flowers and ears of corn.

Above an upper shelf is a concave-sided structure as if part of a curved pediment, bearing upon it a relief carving

of crossed trumpets, hourglass etc, flanked by two conch-like lamps. At the very top is a pot.

Beneath the inscription is a shelf supported by two brackets, and with a central apron with a pair of carved,

winged cherub-heads, and a painted coat of arms, and beneath this, a grim deaths-heaad, with trumpets behind the wings.

Nicely carved.

Catherine Heames, d.1716, and deaths head as a memento mori.

Catherine Heames, d.1716, and deaths head as a memento mori.

- Anna Greet, d.1752, with a religious exhortation, in an excellently delineated script,

but with no other ornamentation, on a panel with upper shelf.

- Selina Salter, d.1754. A fine cartouche (see picture above), with the typical violin-shaped central portion,

domed in the centre, surrounded by carved acanthus leaves and scrolls, with the scrolls at the top left and right being

a bold feature of the monument. Above, a painted shield of arms, more acanthus, and a summit device of a cockerel s head.

The base of the cartouche sits on a bracket with shelf, not an obvious terminus and a jarring note.

- Hugh Ross, d.1775, by Descent a Branch of the Family of the Earls of ROSS of SCOTLAND, by Profession,

a British Merchant... A cartouche, with the inscription on a violin-shaped space enclosed by luxuriously carved scrolls,

painted arms at the top in a mini-cartouche with a raised hand at the top holding a wreath, and the resemblance to the

violin enhanced by the odd protruding base, being a low relief leaf atop a curved, fluted bracket, most unusual.

- Elizabeth Manning, d.1780, erected by her son William Manning, plain rectangular panel.

- William Innes, d.1793, One of the oldest and most respectable Merchants of London,

and a most charitable and worthy Member of Society . A pyramid or obelisk monument, with above the inscription a shelf,

and on this a tall obelisk of dark and light grey marble, with small Grecian pots to each side, one of which is damaged.

The obelisk bears near the top, a painted shield of arms, under which is a carved ribbon, from which depends a large roundel

with a relief portrait of the deceased in three-quarters view. He is shown in middle age, with strong eyebrows,

rather narrow nose, thin, ascetic mouth in a whimsical expression, and firm chin. He is seemingly bald or with very tightly

cropped hair on top, with curls over the ears. In the style fo the day, he wears Classical drapes.

- Elizabeth Forssteen, d.1795, with a sentimental poem from her son. Plain panel with upper shelf

and thin inlaid or coloured black border.

19th Century Tablets

There are quite a number of 19th Century monuments in the Church, mostly without sculptural ornament, so we note them more

briefly.

- Henry Steele, d.1803, merchant, formally of Acrewalls in Cumberland. An obelisk monument,

with the obelisk a little less than half the total height of the monument, and narrow, to allow for a pair of acroteria

to the sides. On the obelisk is a relief carving of a Greek pot. The inscription below has side pilasters, fluted,

and a shaped apron below flanked by two brackets carved with shell designs.

Obelisk monuments, beginning of 19th C: Steele and Ramsay.

Obelisk monuments, beginning of 19th C: Steele and Ramsay.

- Samuel Worthington, d.1805, and wife Sara, d.1783, panel with upper shelf

and small toothed brackets.

- Revd. William Edmiston, d.1806, curate, wife Maria Graham Edmiston, d.1830,

William Johnstone Edmiston, d.1819, and Alexander Coape, d.1819. Panel with upper shelf and blank pediment,

the panel unusually being intruded upon from the dark backing by carved flowers on the corners.

- William Hamlin, d.1810, and wife Elizabeth, d.1810, as for Samuel Worthington.

- Richard Vandome, d.1810, as a tomb chest end, with upper and lower shelf, plain feet,

and a top of carved acanthus leaves, on a dark backing.

- William Morrice, d.1812(?), plain panel with thin upper shelf and a rimless pediment or lid above,

small feet below, on a dark backing. All rather worn.

- William Ramsay, d.1813, Secretary to the East India Company, which erected the monument.

Blocky monument with side pilasters bearing low relief carved leaves with ribbons at the top, upper and lower shelf,

and above, a short pyramid bearing a relief carving of an onion-shaped pot on a base with mouldings.

At the base, two brackets carved with leaves.

- Thomas Read, d.1823, and wife Mary, d.1853, plain white panel with upper shelf

and two brackets.

- Wynen Gerard Wynen, d.1827, merchant, and wife Mary, d.1832, plain panel without surround.

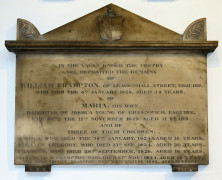

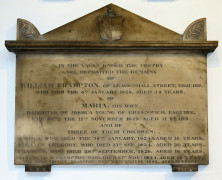

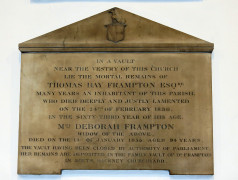

- William Frampton, d.1828, and wife Maria, d.1829, and various children and relatives

added later. Panel with upper shelf, above which is a rimless pediment bearing a small carved shield of arms surmounted by a

greyhound in relief; anemone acroteria are at the sides.

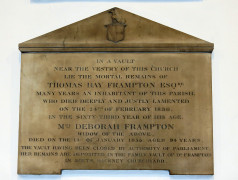

Typical 19th C tomb chest end tablets, to William and Thomas Frampton, and crest.

- Robert Roger, d.1829, plain and humble panel.

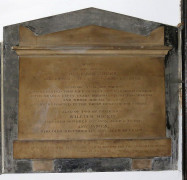

- Gilbert Gibson, d.1832, a surgeon who died of malignant cholera, plain panel on a shaped black backing.

- Susanna Pett, d.1834, panel with upper shelf and shallow brackets.

- Thomas Bay Frampton, d.1836, and wife Deborah, d.1855, plain panel with upper

rimless pediment bearing a coat of arms as above.

- Charles Shuttleworth, d.1838, as a tomb chest end, with lid above an upper shelf, acroteria,

and thick lower shelf with small feet, no carving, all on a dark base. This rather humble work is signed Nixon ,

perhaps a minor work by Samuel Nixon, who has made far more ambitious monuments.

- Peter Jones, d.1840, wife Ann, d.1841, and sons William Hickin, d.1835,

and James, d.1837. In the same style as that to Charles Shuttleworth, and likewise signed, indistinctly, by Nixon.

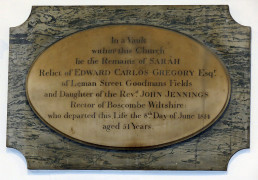

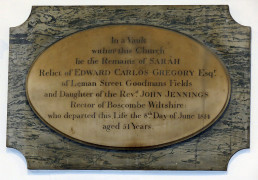

- Sarah Gregory, d.1844, daughter of the Revd. John Jennings, Rector of Boscombe, Wilts.

Elongated oval panel on streaky grey marble backing with nipped corners.

- Sarah Maule, d.1753, of Eckton, in the county of Northon [presumably Northampton],

and son in law Bulkley Banson, d.1761, with a note that the plain tablet was erected in place of the stone

removed to the east end by Daniel Birkett, 1876.

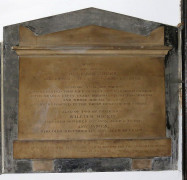

Mid-19th C panels: Peter Jones, by Nixon, and Sarah Gregory, composition based on an oval.

Mid-19th C panels: Peter Jones, by Nixon, and Sarah Gregory, composition based on an oval.

20th Century

20th C in historic style: Baronet Batho, d.1938, and Adrian Stedman, d.1716 (monument of 1983).

20th C in historic style: Baronet Batho, d.1938, and Adrian Stedman, d.1716 (monument of 1983).

Modern brasses

There are about a dozen, dating from the 1890s to the 1920s. The typical modern brass consists mostly of the panel with text

in black lettering, sometimes with the principal capitals in red, an inscribed line forming a border,

and this being sometimes doubled, about a ruler s thickness apart, to give a broader border which typically has

some minor repeating decoration. More detailed ornament is not so common, and where present, is typically a small coat of arms,

for example from a regiment in which the deceased served. These various features can be found amongst the St Andrew s Undershaft

collection, as well as entirely plain brasses. The particular elaboration favoured here is to have a segment of a circle

at the top centre, with a mitre and crook, and there are three of these in the Church, for William Walsham How,

Lord Bishop of Wakefield, d.1897, R. C. Billing, Bishop of Bedford, d.1908, and

Charles Henry Turner, Bishop of Islington, d.1923, all of whom also held posts at the Church at one time or another.

Bishop Charles Turner, d.1923, one of three similar modern brasses.

Bishop Charles Turner, d.1923, one of three similar modern brasses.

The most elaborate modern brass in the Church is that to Philip Anthony Brown, d.1915, and

Theodore Anthony Brown, d.1917, brothers who were killed in action in World War I, with the inscription to each brother

in an inscribed wreath, with Regimental arms.

Also in the Church:

This page does not cover other features of St Andrew s Undershaft, such as the doorways and the stained glass,

but we note at least the following:

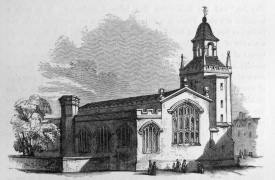

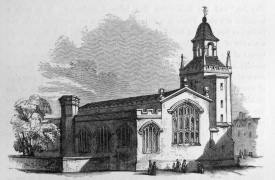

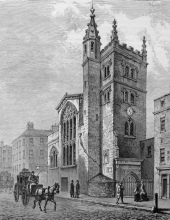

When St Andrew's had a steeple.

With many thanks to the church authorities at St Helen Bishopsgate for permission to use photos from inside St Andrew's Undershaft; their website is at

http://www.st-helens.org.uk/.

Top of page

Just South-East to St Helen Bishopsgate // South across Fenchurch St to St Olave Hart St // Or to the tower of All Hallows Staining // Eatward to St Katharine Cree // or St Botolph Aldgate

City Churches // Introduction to Church Monuments // London sculpture

Home

Visits to this page from 21 October 2014: 10,543

Nicholas Levison, d.1534, and wife - and children.

Nicholas Levison, d.1534, and wife - and children.

Catherine Heames, d.1716, and deaths head as a memento mori.

Catherine Heames, d.1716, and deaths head as a memento mori.

Mid-19th C panels: Peter Jones, by Nixon, and Sarah Gregory, composition based on an oval.

Mid-19th C panels: Peter Jones, by Nixon, and Sarah Gregory, composition based on an oval.

20th C in historic style: Baronet Batho, d.1938, and Adrian Stedman, d.1716 (monument of 1983).

20th C in historic style: Baronet Batho, d.1938, and Adrian Stedman, d.1716 (monument of 1983).

Bishop Charles Turner, d.1923, one of three similar modern brasses.

Bishop Charles Turner, d.1923, one of three similar modern brasses.