Classical girls in the Gothic church

A light-hearted survey of sculpture of Classical females on church monuments, looking from earliest times until the end of their era during the 20th Century, and then taking a number of examples of the variety of this most attractive of monument types. Click any picture to enlarge, or hover for caption.

One day, in the early 17th Century, the great door of a Gothic church swung open to admit a maiden from ancient Greece, in her Classical robes, bare armed and bare footed. She came inside, climbed up onto a monument, and sat right on top of it. Thus started a fundamental change in church monuments: this Classical girl, and her many sisters and cousins - Greeks are well known for their many cousins - stayed on the monuments for the better part of three centuries, until the art of the carved and sculpted monument itself largely died away sometime after World War 1.

Preamble: before the Classical girl arrived

The medieval female figure in the Church (hover for captions).

To appreciate this phenomenon, we have to go back further in time and see what was going on in the ecclesiastical world before our Greek maiden entered into it. In mediaeval times, Church building was rife, and church expansion of older, Norman churches too – new aisles on the sides, extensions to the chancel and nave, towers thrusting skywards – all in the new Gothic style, which itself changed and evolved through Early English, Decorated and Perpendicular styles. Sculpture lagged behind, with the Norman knights of the 12th Century - think Temple Church - leaving sons and grandsons in similar costume well after England’s great Gothic cathedrals were being built. But by the 14th Century, some of the monumental statues of women, if less of the men, became slender and elegant in their medieval Gothic costume. Through into the 15th and early 16th centuries they continued thus, and while fashions changed, and hairstyles, the female form was generally admired in monumental sculpture: still in medieval form, with slender, small-breasted and long bodied, with delicate arms and long, narrow fingers.

Tudor and Elizabethan (hover for caption, click to enlarge).

Two things began then to happen to monuments: firstly the numbers went up greatly, as the rather small numbers of grand lords and ladies were joined by an increasing number of monuments to wealthy knights, merchants, landowners and servants of the state, and secondly the move to a bulkier, Tudor look: pantaloons and cloaks for the men, broad dresses and skirts for the women, and many layers for both. Effigies lying on their backs rolled over on their sides (above left, click to enlarge), and then got up on their knees, with husbands and wives facing each other across prayer stools, in the era of the kneeler monuments. [See this page for lots about them]. By 1600, these dominated figure sculpture, and while the sculptors were often skilled and with subtle knowledge of the human form– we only have to look at the faces and the hands to see that – the costumes of the day meant that the female form was lost: rather, a big black dress (for these statues are generally painted), splayed out to give a triangular form, usually a big ruff so there was no neck, and often as not a big hood or hat over the hair (picture above, centre). As well, the wife, or last wife of several, often long-outlived the husband, so that the monument to a couple would often have a plump, fresh-faced man, and a much older, skull-faced widow opposite (picture above right).

Historical Survey of Statues of Classical Girls:

The first Classical girls arrive, about 1630.

Our Classical girl therefore, when she came upon the scene, was a complete figural departure, going back to the early medieval stress on the elegant human form, but different proportions, being longer of leg, more rounded in form and with a new muscularity to arm and thigh and neck. How could she fit in with the squat, triangular females the monuments were centred on? The answer was for the Greek maiden to go to the top of the monument. While the centrepiece of the monuments were almost invariably a scene of Christian prayer, the frames were Classical by now, with Romanesque arches, Ionic and Corinthian pillars and canopies to make little temples above the figures. The top of the monument and flat surfaces could be very busy affairs with something of a variety of styles: lots of heraldic devices, combined with strapwork and mediaeval curls and grim little skulls and other memento mori like hourglasses; dumpy pots and low relief ribbons and little cherub and lion heads.

Early Classical angel girls, on the busy top of the monument (hover for captions).

It was easy enough for our Classical girl to slip in here, often flying in as an angel rather than climbing up, and settle herself down on the sides of the pediment, sometimes allegorical, representing some attribute of those commemorated below, such as Fame, Justice, or Faith, or perhaps just represent something universal, like Time. These early Greek girls were generally small compared to the principal figure or figures, and separated as they were by being outside the central portion of the monument, at the top (picture above left), or later at the sides (above right), a clear enough distinction could be made that there was no jarring discrepancy between the Tudor or later Elizabethan or Jacobean dress of the central figures, and the light robes and bare feet and arms of our Classical figures.

Classical girls at top and side of panel without central figure.

An alternative was to dispense with the central figure altogether, and just have a descriptive panel, augmented by a Greek maiden or two. The examples above show different positioning of paired figures. Hover for more detail.

The Classical girl becomes the principal figure.

There was no doubt though, that the dumpy kneeling woman, however large and richly dressed, was at a great disadvantage compared to the more flattering look of our subsidiary Greek girls. And so the fashion in monuments changed towards the end of the 17th Century, so that the Classical figure took over the whole monument, with the principal figure or figures commemorated being in Classical drapery too: the examples above are from the early, late and turn of the 18th Century (click the central one to read the poetic eulogy). Where it was just the girl – draped over a funereal urn, sitting next to a headstone, or perhaps under a dying tree, this worked splendidly, but where she and her husband were both present, there was often an awkwardness as we can see below

The Classical girl and her bewigged 18th Century husband.

In this though, the man was somewhat behind his consort, for while the wife immediately and comfortably adopted full Greek attire, the husband tended to be attached to his wig. And while the wives, now they were freed from their more bulky clothing, could exercise and quickly adopt the Greek physique, this was often less true of their husbands, who might retain the stomach and jowled chin of the 18th Century man of leisure. This was particularly so where the family went Roman rather than Greek, for while her apparel could remain fairly similar, though always sandaled rather than the choice of barefoot, and with hair typically shorter and tighter to the scalp, he had the opportunity to dress as a Roman soldier, which would only make that stomach more prominent - example above left.

18-19th Century Classical girls, comfortable and relaxed.

And then, finally, by the mid 18th Century and through to the 19th, our Greek girl was entirely comfortable. She could pose with a Classical pot, or a graveyard monument, or all the tools of allegory – the anchor, the bible, the cross, the book, the flag, whatsoever the sculptor pleased. If there was a man in the ensemble, he could be Classical, but equally in modern clothing, with she as an angel or symbolic figure rather than spouse.

The Classical Girl as an Angel (hover for notes).

A variation on the Classical girl theme of course is the Classical girl as an angel, who was always floating around - we saw a few earlier examples higher up this page - but became increasingly prevalent towards the end of our period. Above, we have a late 18th Century one on an obelisk monument (see this page for lots of those). Then two 1820s examples, one a triumphant angel with a trumpet, the other a mourning, kneeling angel - this latter one is by the sculptor J.G. Bubb and is one of a pair (click to enlarge and see the other). The final example above right is late 19th Century, and is a Classical Arts and Crafts angel: the sculptor was American, Henry Waldo Storey, who, along with his father William Wetmore Storey, has various statues in the UK. So that brings us to the end of our period: already by Victorian times, more and more Classical girls were unsentimentally departing from the monuments, going outside, breathing the air and wandering off to find new homes in architectural sculpture, and in the form of angels, in the Victorian cemeteries, where they carried on arriving for a generation after their last sisters inside the church. See the Introduction to Churchyard and Cemetery monuments for a few of these monumental outdoor Classical girls, and all over this site for the architectural variety.

The Classical girl returns outdoors, 19-20th Centuries (hover for captions).

Examples and Range of Classical Figures:

And now to some individual examples to show the variety of forms and styles. We start with Classical females on grand monuments by the excellent 18th Century sculptor Henry Cheere.

1730s Classical girls by sculptor Henry Cheere.

Above left, the Susannah Thomas monument, by Henry Cheere perhaps assisted by William Powell of Hampton, in Hampton Church. A strong, triangular composition of a pair of females in Hellenistic dress, lounging as if by a pool – but the one has a book in hand, and their soft faces with their somewhat double chins are as far from the ancient Greek ideal as can be. Above right, the Robert Raymond monument, certainly by Henry Cheere, in Abbots Langley. She is dressed in Classical drapery, while he has a full wig, frilly ruffs to the sleeves, and flat ended shoes, and broad, self-satisfied face purely of the 18th Century.

Classical and modern: Elizabeth Grieve monument.

Here we have a nice frieze; our Classical girl, who is Elizabeth Grieve, d.1757, is a soul taking flight in correct Ancient Greek drapery, Temple of the Winds style. Her oblivious 18th Century physician husband is well wrapped in more indeterminate drapery, but has his nose in a book rather than a Greek scroll, and with a not very Classical dachshund under his chair. An aged figure of Time, more Germanic than Greek, is behind, and for good measure, Death as a cowled skeleton with dart poses behind. Rather medieval snakes coil in the spandrels (for a note on snake sculpture, see this page).

Classical souls ascending to heaven.

Now that monument is a fairly early example of one where our Classical girl is a soul being taken up to heaven. This is something which earlier generations frowned upon depicting, as it rather presumed on the Deity's judgement. By later in the 18th Century, all such qualms were gone, and it was taken for granted that heaven was the direction of travel. Three more examples above, all by big-name sculptors: John Flaxman, Sir Richard Westmacott, and Edward Hodges Baily (hover over pictures for captions).

Classical busts.

Here are three examples where the subject of the monument is a Classical bust. The first two, one in the round, one a high relief, both date from 1698, and show rather similar treatments of the face and hair: not ancient Greek Classical, with a fullness to cheek and chin and a nose shape which would never have been allowed, but an ideal rather than a portrait, with a calmness of expression, a full figure, and stillness of pose. She on the right, much more recent, is Dorothy Westmacott, poignantly rendered by the sculptor Sir Richard Westmacott RA, whom we have already met. A different treatment of the eyes and a little more character to the face, and posed with a sense of movement.

Classical girls and Classical pots.

Very popular from the late 18th and early 19th Century are the Classical girl and pot, a funereal urn, on which she typically leans while often standing cross-legged in what seems a rather casual pose, which gives ample opportunity for the drapes to swirl round the body and legs, giving a fine effect of light and shadow. Here are three examples, with differing treatments of the theme and a variety of Classical pots.

Classical girls and Classical pillars.

Here are two examples of Classical girls and pillars, also convenient for the elbow. The one on the left, with really elegant drapery, is a masterful piece in Richmond Church by John Flaxman. Note the portrait roundel of the deceased lady. The rather simpler treatment on the right, with bold lines to the drapes, is by a less-well known sculptor, Thomas King of Bath and is in Monken Hadley Church.

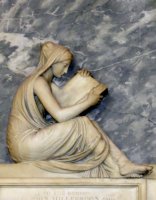

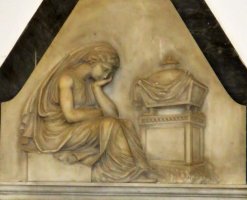

Classical girls and Classical tombs.

Along with pots and pillars, Classical girls can be found with a variety of other tomb types, offering many possibilities for composition. Above left, a Dagenham Classical girl, seated next to a casket tomb, another fairly popular type. Here she rests her elbow on her knee rather than the tomb itself. Above right, in Bilston, a Classical girl carrying a basket of roses drapes herself on a tall tomb chest.

The Classical Girl and the Tree.

And here is an example of a Classical girl, again with a pot on a plinth, under a dying tree. The dying tree was used a symbol not just of death, but of the death of a supporting figure. The Classical drapery here is very simple, but with strong curves reflecting the curve of the tree in the composition.

Classical Girls by Classical sculptors (hover for captions).

And to end, I wanted to include a few more of the more significant sculptors of our Classical girls. We have already met Henry Cheere from the 18th Century, John Flaxman from the beginning of the 19th, and Sir Richard Westmacott RA and Edward Hodges Baily takie us into Victorian times. To these, the group above add, from left, Nicholas Stone the Elder, early 17th Century; Louis-Francois Roubiliac (who worked in England), mid-18th Century, John Bacon the Elder 1790s, and Francis Chantrey, early 19th Century. The variety of figure composition, the treatment of the drapery, and the move from full figure to high and low relief show the imagination and enthusiasm with which the sculptor turned to the one of the most absorbing subjects for monumental carving: the Classical girl.

Bob Speel.

See also: Kneeler monuments // White-on-black monuments // Obelisk monuments // Winged cherub heads, mostly on monuments // Skulls, mostly on monuments