Monuments in Abbots Langley Church, Hertfordshire

Abbot’s Langley is a few miles, or a short bus ride from Watford, in the southern part of Hertfordshire. The Church of St Lawrence is not so prepossessing from the outside, consisting of a stubby buttressed tower, short nave with a roof almost as high as the tower, then an extension, and aisles on the sides. The materials are a mix of flint, flint and stone chequer work, and brick, and apart from the tracery of some of the windows and the odd weathered corbel, there is no sculptural decoration at all. But it is old – the nave, as can be seen from the interior, is Norman, late 12th Century, the tower dates from around 1200 and later, with the parapet at the top being modern. Other parts of the Church are from 1400 and later.

St Lawrence Church, Abbots Langley.

Inside is more interesting than the plain exterior. Solid pillars divide the narrow nave from the aisles, with Norman, dog-toothed arches between (see top of page). And the dominating feature on entering the Church are the two grand monuments against the nearer wall, by the eminent and skilled sculptors Henry Cheere and Peter Scheemakers. We start with these two, and then consider the rest in date order.

Henry Cheere's monument to Baron Robert Raymond, d.1732.

Robert Raymond, Baron of Abbots Langley, d. 1732, with a long Latin inscription. The Baron is shown reclining, Roman fashion, but in full wig and clothing of his time, including ruffs at the wrists and a mantle on which rests some chain of office, though his long robes are treated in a sort of Baroque Hellenistic Classical manner. One hand gestures expansively, the other holds an unrolling scroll; the whole figure is imbued with pride and satisfaction and pomp, and is a splendid piece of virtuoso carving by Henry Cheere. To the left is seated the Baron’s slender and youthful wife, who is wearing proper drapery, again treated in Baroque fashion, with the usual light upper garment and heavier folds of cloth over her legs; a gathering of her cloak is draped over one arm. One hand touches her breast, indicating her heart, the other holds a portrait roundel, presumably of her husband when younger, in relief, held so that the full statue of the Baron could gaze upon it. She too is proud in stance. On the other side of the monument, at the Baron’s feet, stands a naked putto, with little wings and holding out some coronet towards the outstretched hand of the Baron. The inscription is underneath, on what is carved as the side of a long tomb chest upon which the Baron reclines with his attendant figures. Behind, a tall black obelisk rises, which bears the family’s coat of arms, with the supports as two free-standing eagles wearing collars; a coronet with little dragon floats above, and the family motto is written in fine script underneath. The monument is also signed by the architect, Westby Gill. Truly a flamboyant monument worthy of a great cathedral.

Lord Raymond, d.1756, by Peter Scheemakers.

Lord Raymond, d.1756, who is, I understand, the son of Robert Raymond. The second grand monument in the Church, by the sculptor Peter Scheemakers, alas with the front covered in when I visited. This again has a tall, dark obelisk, and here this is more of a feature of the monument (see this page for more obelisk monuments); in front of it is the end of a table tomb, with upon the front a wreath with crossed flaming torches across a wreath carved in relief. Seated atop the chest is a cushion which bears the coat of arms, as we have seen it on the earlier monument with the two large supporting eagles, but here rather low down on the backing obelisk. To each side is full sized female figure in white marble. On the left as we look at it is a girl mourning, handkerchief to her face, though her elbow is in casual 18th Century fashion resting on the edge of the tomb. Her other hand rests on her leg and upon a cornucopia from which emerges a large bunch of fruit. She wears classical drapes of course, her cloak hanging away from her body above to emphasise her slender figure, and her long skirts giving a satisfying sweep of drapes at middle height, and with her sandalled feet peeping out at the base; she is seated upon a rock. The figure as a whole consciously echoes the pose and drapery of Henry Cheere’s female on the older monument, most satisfying to the viewer. On the other side of the monument is our other female figure. As with the first figure, her legs face outward, her head turned inward, but the pose is rather different, with the feet somewhat more apart giving a bold composition to the legs. She has one hand across her chest, indicative of her heartfelt feeling, the other holds a small anchor resting upon her knee. Her face is youthful, her hair beneath a crown of flowers is pushed back so as to expose her neck to the full; we see that this neck, and her exposed arm, are gently muscular in an understated fashion. Again, an altogether excellent thing. To have a monument by one of the great 18th Century sculptors is to be praised; to have the work of two is really rather special.

On to the rest of the monuments, which include some figural work and some simpler panels. We take them, as is the convention on this website, in date order:

- Johannes Lewes Brito, d.1626, with a long inscription in Latin, black capitals with initials in red,

a cracked board within a narrow modern frame and no surviving sculptural surround.

Monument to Anne Combe, d.1640, with Death and Time.

- Anne Combe, d.1640, daughter of Thomas Greenhill, Gent, and wife of Francis Combe (d.1641),

who made charitable bequests to Hemel Hempstead, Berkhampstead, Watford and St Albans, as well as Abbots Langley itself,

including lectures, for schools, and giving the Manor of Abbots Langley and some lads and most of his library

‘(himself being learned)’ to Sidney College, Cambridge and Trinity College, Oxford. A grand monument of alabaster and marble,

centred on the kneeling statue of the deceased, holding a small book and with a prayer desk in front of her with a larger book.

To each side are dark Corinthian pillars, supporting a broken pediment, richly decorated, with upon it a large carved

and painted coat of arms and side obelisks with balls at base and summit. To the sides of the main figure are small figures

as momento mori. Thus on the right, a standing figure of Time as an old man with a scythe and carrying an hourglass,

and to the left, this being 1640, a standing skeleton, wearing a long robe, again carrying an hourglass,

and also a downward-pointing arrow. As is usual for the time, the skull has no lower jaw,

which looks odd on an otherwise complete skeleton. At the base of the monument, underneath the inscription,

is a gilt cherubic head in low relief with a bit of strapwork. The whole edifice is characteristic of such kneeler monuments,

of which this is towards the end of the period, but this is a particularly fine example and the side figures are a feature.

Dame Anne Raymond, d.1714, and detail of grandchildren in cribs.

- Dame Anne Raymond, d.1714, and three grandchildren. She was daughter of Sir Edward Fith (?),

wife of Sir Thomas Raymond, Knight and a judge of the King’s Bench to King Charles II, erected by her son Sir Robert Raymond

of Langlebury, Kt, who erected the monument and was the father of her three grandchildren, who all died as infants.

The inscription is on the base of a portrait statue of Dame Anne, seated and facing forward, shown in middle age,

and wearing a thin shirt, finely carved and outlining her body. She also wears a hooded cloak, and has longer,

heavier drapes on her legs, fairly symmetrically disposed and most harmonious. Her lower arms are bare,

and rest on the armrests of her chair; one hand, damaged, is open; the other holds a book. She sits within and forward

from a Romanesque arch, which provides an elegant frame. To left and right are tall, fluted pilasters, with outer scrolls,

and above is a central cartouche painted with a coat of arms, and pots to the side. Below, a double apron has on its upper level

a relief panel carved with the three wickerwork cribs of the grandchildren, rather poignant, and beneath this is a great,

broad corbel bearing Acanthus leaves above a central flower. A grand monument, and extremely well composed.

The only fault is in the shortness of the figure’s legs; I think this may be an attempt at foreshortening

which does not quite work visually.

Detail from panel to Thomas Howe, d.1719.

- Thomas Howe, d.1719, and wife Mary, d.1716, daughter of Paul Priaulx, Citizen and Merchant of London, erected by their son Thomas in 1722. White panel with white and grey marble surround, forming flat pilasters, curved completely broken pediment, on the top of which is a pot with large trail of carved flowers each side to form a rough triangle. At the base are two deep side supports, mini pillars resting on corbels in a darker streaked marble, with between them a panel bearing fronds and a cartouche shield, now blank. At the very base is a winged cherubic head. A characteristic somewhat Baroque monument of the period.

- Jannet Mathew, d.1812 (the spelling is correct), put up by her daughter Lydia Payne Botham. Panel with upper shelf bearing a wide pot in low relief, with carved leaves round the base and a missing top. On a grey backing cut to give a pediment above and little feet below.

- John Dixon, d.1819, and wife Susanna Dixon, d.1820, white panel with upper shelf and lower feet of on streaky grey marble shaped backing.

- John Harness, d.1823, Medical Commissioner of the Transport Board. With shelf and curved base, on a matching grey backing, oddly clamped at the sides and top with metal clamps. Signed by the mason T. Bedford, 256 Oxford Street.

- Henry Botham, d. 1825, plain panel with inscribed grey marble border, roundels at the corners.

- Lydia Payne Botham, d.1838, whom we met before, panel with upper shelf bearing a small elegant pot, carved with moulded base, small drapes, and a delicate curved handle with a further drape – too delicate, for the second handle is broken. On a shaped black backing.

- George Ranken, d.1856, plain brass panel presumably of later date. He was a Major in the Royal Engineers and the last British Officer killed at Sebastopol (Sevastopol).

- George James Sulivan, d.1858, Captain in the Royal Horse Guards Blue.

As a tomb chest end (see this page for more such things), with upper shelf and pediment or cover, and little round corbels at the base, on a narrow grey backing.

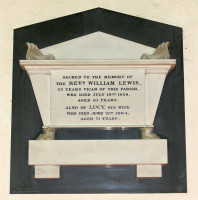

Revd. Lewis monument, d.1858, by M. W. Johnson.

- Revd. William Lewis, d.1858, Vicar, and wife Lucy, d.1864.

As a casket end, with shelf, cover and finely carved acroteria (ears), lion feet below, standing on a shelf with two brackets,

all on a shaped black backing. By M.W. Johnson, 363 Euston Road, London. Rather late for this style.

Ambrose George Armstrong monument.

- Ambrose George Armstrong, undated late Victorian. A remarkable thing, and a memento of a type of

sculptural decoration once widespread in libraries and great houses, being the coloured relief sculpture panel.

The monument is effectively a triptych, having a narrower central portion and two broader sides,

all surrounded by gilding and separated by Ionic fluted pilasters. The central part consists of a high relief portrait

of the deceased, as a schoolboy, in a semicircular panel, coloured, and surrounded by gilt. Beneath is the name ‘Ambrose’

on a narrow panel of carved olive branches, again gilt, and beneath that is an inscription in Latin.

The panel on the left is a scene showing a ragged boy in the background surrounded by figures, and in the foreground,

ascending the steps which fill the mid-ground, a couple, the wife raising her hand to better focus attention on the figure

of the boy. Two pigeons rest on a step for compositional reasons. All very biblical.

The right hand panel shows a Virgin and Child with attendant angel musicians against a landscale with blue sea,

sky and a single fruit tree, in a sort of late Alma Tadema style, but rather sentimental.

Apparently these two panels represent The Flight in to Egypt and Jesus in the Temple, but I would not have thought it.

Narrow panels above include half a dozen double-winged cherubic heads in low relief; more Latin on the friezes below.

At the very top, on the cornice, are freestanding pots at the corners, and two small figure groups, all gilt;

the one showing a scholarly figure writing at a desk, and the other being a St George and the Dragon,

with the knight having wrestled the hapless Crocodilian beast to the ground, thrusting a short spear between its gritted teeth.

A small bronze panel underneath notes the monument is the work of the deceased’s father, Thomas Armstrong, d.1911.

The whole thing is rather sentimental, religious in an illustrative rather than pathetic way, yet we can take it as a piece

of art of its time and enjoy it.

Sir John Evans, d.1908, in archaic style.

- Sir John Evans, d.1908, Knight Commander of the Bath, Geologist and Antiquary, a panel of rock showing heavily folded strata, as befits a geologist, with a long, tightly set inscription describing his various accomplishments and posts. The surround, as befits an antiquarian, d is in the fashion of the 18th Century, white marble, with frame, outer scrolls, upper curved pediment bearing two painted shields, knight’s helm and lots of acanthus, deeply carved, and at the base an apron with portrait roundel of the deceased in low relief, surrounded by a winged wreath.

- Edward Wynne Chapman, d.1914, Lieutenant in the 3rd (Prince of Wales) Dragoon Guards,

who fell at Ypres. Bronze panel with repeating foliage design around the edges, small coat of arms of his regiment,

and corner crowns with feathers.

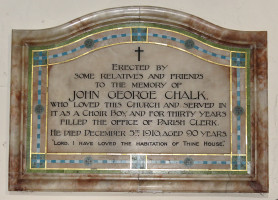

Tablet to J.G. Chalk, d.1916, with mosaic decoration.

- John George Chalk, d.1916, a charming red-brown and beige alabaster panel in an arts and crafts manner popular from the end of the 19th Century through to the 1920s. The elegant text is surrounded by a border of inset mosaic in gold, blues and greens, within an outer frame. Colourful and decorative.

- Bernard Hale, undated, with lines written by David Garrick, white panel with curved top, outer border of brecciated dark marble, curved shelf above, as if a broken, curved pediment, and apron.

- Catherine Eliza Henty, d.1925, plain brass panel.

Also in the Church:

- Rauffe Horwode, d.1498, with his two wives, Elizabeth and Josue?, and six children. Brass where we have the inscription, but the figure of Rauffe himself is gone. The two wives look essentially identical, standing, forward-facing figures with large heads and crude hands, dressed in long robes, and with trimmings of fur. The children are better: to the left, three sons, monklike figures with decent drapery over the arms: we may take these as likely representative of the missing figure of Rauffe. To the right, the daughters, slender-waisted creatures, two with their hair covered, the youngest with hair unbound – there is a certain spiritedness to these offspring.

- Thomas Cogdell, d.1607, a brass showing him and his two wives, one on each side.

He stands centrally, facing the viewer, while they are in three quarters view facing somewhat towards him; a nice grouping.

All are standing on cushions, praying, and have rather simple draperies, excepting that the two wives wear fine hats

and have large ruffs. A good piece of its type.

The Cogdell brass.

- Among several medieval paintings, two paintings by the Chancel arch, being two bishops, one carrying a crucifix and wearing a mitre, and the carrying perhaps a flaming branch, and standing in a dynamic posture.

- Several corbels, showing musician angels, of uncertain date; rearranged after a fire in 1969.

- A Royal coat of arms painted on board, dated 1678, thus in the reign of Charles II.

- Various ledger stones, including for example that to the Revd. John King, d.1679 and his wife Elizabeth, d.1672, with a coat of arms with ammonite-curled feathers from the helms on top.

- An octagonal font with relief carvings of various devices in quatrefoils,

including evangelical symbol: an eagle, winged lion, winged bull and angel, with heraldic shields on the intervening panels.

There are small blank Gothic windows on the shaft, painted but rather disfigured by time.

15th Century according to the Royal Commission on Historic Monuments, late 14th Century according to other sources.

The font, decorated Gothic style.

- Some good late 19th Century stained glass, with standing saints in bright colours: a St George with a certain boldness of treatment (see top of page), and a St Margaret, both with ideal faces in a 1900s style. The main window dates from past the turn of the century, and has a scenic treatment including a cave with clustered stalactites, a mountain range with corn in front, animals including an elephant, and nouveau angels.

- A panel, presumably contemporary with the Brito memorial of 1626, with black script and a few red capitals setting out the 10 Commandments, with a modern wooden frame.

- Several plain panels in memory of those who fell in World War I and World War II.

- A panel of 1924 noting that Nicholas Breakspear, later the English Pope, Adrian IV (1154-59) was born at Bedmond in the Parish, the panel being put up by the Hertfordshire Historical Association.

- A board inscribed with the Church vicars back to the 14th Century.

Stained glass in Abbots Langley: angels, cave with stalactites, and light falling on a ledger stone.

Outside, an extensive atmospheric churchyard surrounds the Church, with various of the usual types of monument, headstones of Gothic and Classical design, many crucifixes, a wooden board monument, raised ledgers, and so forth. There is a war memorial in the form of a tall Churchyard cross, stone and bronze, but no sculptural detail.

Nearby the Church, by the library is a chunk of the local building stone, Hertforshire puddingstone, collected by Frank Cooper, d.2006, of whom the stone is a memorial. Round the corner, the Catholic Church has a large modern sculpted mural with central Christ figure, quite austere, and the symbols of the four evangelists. It was made by David John of Reading, an ecclesiastical sculptor, whose work may be found for example at the church of St Luke (also R.C.) Pinner - see bottom of this page.

With many thanks to the Church authorities for permission to show pictures of the monuments inside; their website is http://abbotslangley.org.uk/about-us/church-history/.

Nearby King's Langley Church