Sculptured skulls are almost always found in funereal monuments, and occasionally on the gates of churchyards. They usually act as memento mori – literally, ‘remember that you will have to die’ – originating from the ancient Roman custom that when a great war leader returned from a successful battle and was feted in triumph through Rome, a slave standing behind him would whisper a similar phrase to stop him becoming too self-opinionated. So for our church monuments, the skull is generally a reminder to onlookers that they too will die, if perhaps they are enjoying themselves being alive whilst looking at the memorials to the dead, or forgetting death while they are engrossed in the interest of the inscriptions, or for readers of these pages, the art of the sculpture. Other common memento mori are hourglasses (time running out), gravedigger’s tools, snapped flowers and withering bushes.

Typical kneeler monument with infants holding skulls, and a close up of such a child.

But we start in Tudor and Elizabethan times, with those wonderful kneeler monuments, where the skull is used differently. Many of these pieces show under or behind their parents, ranks of children, and where the child did not survive, this is indicated with a little skull, either held in the hands, or on the pillow which the child kneels on. A couple of examples are above. It is as well to mention now that by convention, it is more usual than not that our carved skulls in church monuments, and largely outside too, are without their lower jaws. I do not know why this should be.

Here we have another Elizabethan family, with a floating skull above the prayer desk to show both parents are deceased. This is quite an unusual case, as the impression is as if the kneelers are praying to the skull – not the intention at all. More usually, a small protruding skull like this would be a little higher than the figures, perhaps on the entablature of the arch which invariably rises above suck kneelers.

Carved couples without skulls, with one holding a skull, and just skulls.

Here is a nice group of monuments. To the left is a typical example of a double portrait, with two busts or half figures facing forward towards the viewer – such pieces were an alternative to the kneeler monuments of the times. In the centre, a similar piece, with the man resting his hand on a skull – like the child-kneelers we saw above, this shows that he had died when the monument was put up, in this case by his wife who was still alive. The third example, on the right, dispenses with the busts altogether and just has the skulls looking mournfully at the spectator. This grim but excellent piece of sculpture is from the monument to Thomas and George Hyde, in Aldbury Church, Hertfordshire.

Skulls and bones in the charnel house, Dame Leonora Bennet monument.

One more grand early church monument. Here is a carving of the heaped up bones and skulls of the charnel house, seen through a grill, most macabre, under the effigy of Dame Leanora Bennet in Uxbridge Church, Middlesex, West London. The use of such imagery recollects the Medieval custom of showing the effigies of great abbots and archbishops above sculptures of their emaciated corpses.

And now to simpler memento mori. The Tudor and Elizabethan monument, typically of alabaster, in the main, allowed much space for small memento mori carved in relief. Four examples are above. The aim was to include a skull or two, perhaps along with the hourglass and other memento mori, but rather small, so as not to become a main feature of the monument or detract from the figure work. Above left, a skull and crossbones with an hourglass below and a ribbon, delicately carved. Next, a marble rather than alabaster skull looking out through ferny leaves. To the right, a delicately winged skull with what appears to be mandibles below, surrounded by decorative ribboning. And to the far right, a vigorously delineated low relief carving of a skull and crossbones with space-filling vegetation around it.

Carved skulls from 17th Century monuments.

Plain skulls are found too. Above are 17th Century examples of two fairly widespread types. To the left are examples where the skull is facing forwards, surrounded by the straplike decorative carving in relief known simply as 'strapwork'; the second of these includes what look to be berries in the design. To the right are examples of where a pair of skulls sits on a shelf, where in another monument of this sort of date there might be small obelisks or flaming urns. The skulls face outwards so we see them in profile, and are carved in the round. Not so common. The portrait bust above, second right, I should mention, is Mrs Pepys, wife of Samuel Pepys the diarist, and is in the church of St Olave Hart Street in the City of London.

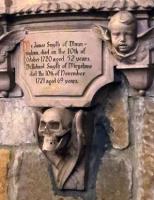

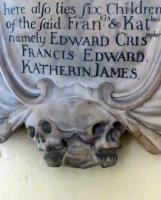

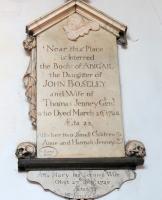

18th Century monuments with carved skulls.

Now these pictures, above, show skulls from 18th Century monuments, for the fashion continued rather similarly to the previous century or so. As before, there are a mix of relief and en ronde examples, and the one on the far right may well have been recut in some repair to the monument in the 19th Century.

Skulls peeping from under carved drapery.

One interesting variant, rather uncommon, is the ‘peeper’ skull, which peers coyly out from beneath a piece of drapery. Typically, the carved inscription would be directly above, as if written on a wall hanging, and so the skull and the reminder of death is directly associated with the deceased, rather than a part of the surrounding embellishments.

And back to the Elizabethans, below is one nice example of a gravedigger with a skull; this sort of naturalistic use of the skull is unusual indeed.

While we are back in the 17th Century, we should at least pay a nod to the full skeleton in funereal sculpture. It is quite a lot of work to carve a full skeleton, so smaller examples are favoured, or at least those in high relief, but here are a few examples. On the left, a girl in the bloom of youth is dancing with Death, who presumably carried her off at a young age. Next, part of a Doom carving, with souls (hence naked figures) being separated to go up to Heaven, or as here, being pulled down to the underworld by satyrlike demons and skeletons. There used to be a number of such scenes either inside the church, or above the doorways to the churchyards. The third picture above is an important panel monument, to be found in the church of St Leonard Shoreditch in East London, and is in memory of Elizabeth Benson,d.1710, carved by the master sculptor Francis Bird. The figure on the far right, a 'skeleton angel', or rather a winged figure of Death, shown with his hourglass, the implication being that when the sands run out for some mortal, he will throw his arrow to pierce his heart.

Carved skeletons in the church: a maiden dancing with Death, a Doom, skeletons ripping apart a tree, and Death as a skeleton angel.

Returning to our skulls and putting other bones aside, apart from the odd femur or two, we move now to a point towards the end of the 17th Century, when we see the appearance of a new and important type, the winged skull, or Death’s head. They are the grimmer counterpoint to the winged cherub’s head (lots of cherubs on this page): whereas the cherub indicates the soul going to heaven, the winged skull is an allegory of the perishing of the body. In some cases they really do simply substitute the skull for a cherub head, and keep the same goose or pigeon wings, as in the examples below; we see that the wings can seem to come out from invisible shoulders below the skull, or be bitten by it, and to vary considerably in size.

Carved winged skulls (bird wings).

We may note that while there are a goodly number of examples on architectural Classical tablets, based on a rectangular shape, pillars or pilasters to the sides, shelf and perhaps pediment above, by far the majority of winged skulls are found on cartouche monuments, those beautiful sculptural monuments in the shape of a turtle’s carapace or violin, surrounded with carved drapery, scrolling and Acanthus leaves. Such monuments often include winged cherub’s heads, and what better to set of a pair of these than a Death’s head? We may see winged cherub’s heads to the sides and a winged skull at the base, or sometimes a cherub head to the left, and skull to the right as we look at the monument. The one place where it is not the done thing to place the winged skull is at the top of the monument, as that is reserved for the heraldic arms, a flaming funereal urn, or something heavenly.

A Classical tablet and cartouches showing winged skulls in the composition.

Now the full flowering of the Death’s head, if such we may call it, comes with a slightly different form, where the wings of the skull are those of a bat rather than a bird. Surely these are some of the grimmest and most powerfully evocative of sculptural imagery in the church. The two central examples below combine the skull with flowers, that on the left wears a wreath on his head, and that on the right seems to have trumpets behind, though given the leaves or petals around, they may be recut as such from original and perhaps damaged flowers.

Bat-winged skulls in sculpture: the true Death's head.

Below are some more examples of this type of monument. The one below left has very complex webbed wings, and looks to the right, which is far less usual than looking forward or to the right. The triangular form of the wings in thh second example below is found in various examples, and makes a good terminus or corbel at the base of a monument. The two winged skulls below right are variants of a type, with the first being particularly well carved and gruesome; again, the wings are complex.

Of the bat-winged Death's heads, I think those with crossed rather than stretched out wings give some of the more macabre and disturbing imagery found in our churches. The wings are more batlike, more like a praying mantis above, and more like grasping hands below. The examples below are all in the corbel, or lower supporting position. Note that the far left one retains his lower jaw, and thus some ligament to attach it behind the upper jaw; there are other cases of this in the pictures above. Note too that a slight change in the size of the features can make a great difference to the overall effect, with the example below right looking particularly malevolent - it is something about the modelling of the frowning forehead and the pinchedness around the nose.

Bat-winged skulls carved with closed wings.

The cartouches had passed their peak by the 1730s, and so too the bat-winged skulls which sometimes adorned them, though the odd Death’s head does appear though till the 1760s at least. By the 19th Century, the skull, whether as memento mori or indication of someone’s death, or Death’s head, were gone, and the Victorians, though they brought back the winged cherub head with enthusiasm, had no taste for the skull in any form. Although the Victorians were very fond of allegory, we can notice in passing that the winged cherub head in 19th Century monuments would seem to be more to indicate purity or to be purely decorative than particularly to recollect Heaven.

Let us go outdoors now. The entrances to a few churchyards are marked by skulls, or skull and crossbones; many more have perished. The piece second from the left below is an unusual survival on a tall monument rather than a gate; you may need to click to enlarge to see the little skulls properly.

Skulls at the churchyard gate.

In the Churchyard, there are examples of 17th Century skulls on headstones, but for the simple reasons of decay and sinking until they are buried, by far and away the most common type is the 18th Century skull, or skull and crossbones, of which a few examples are given below, with the one at the far left being 17th Century. Note that by convention, skulls face to the left (sinister), unless there is some good reason otherwise, as in the monument to two sisters, central picture below. There is a variety of crossed bones below or behind the skull, crossed frondy branches, and the skull biting on something, as in the picture below, second from right. Such headstones with carved skulls can be found across the country in the churchyards, but all too often they are worn away, until a skull is hardly to be distinguished from a cherub head, and finally to disappear entirely.

Skulls on headstones in the churchyard, carved in relief.

There are also 18th Century examples of skulls on other types of monument: altar tombs and occasionally at the bases of pyramids, an example being below, far right, where the skulls are actually supporting features.

Tomb chests with carved skulls on the edges and the side panels, and skulls supporting an obelisk.

Outdoor headstones were made en masse for a much wider and less wealthy clientele than panels inside the church, and the masons who made them, and likely the families of the deceased, generally tended to the conservative, so that styles of outdoor decoration tend to considerably lag those inside the church. So for our skull sculpture, the outdoor examples lasted till the end of the 18th Century, and even a few examples almost up to Victorian times, long after such embellishments were abandoned in monuments inside the church.

Non-human skulls in architecture and allegory.

Finally, we might mention a couple non-funereal example of the use of skulls, but not those of people. Occasionally, a bull’s skull with its horns may be used as a decorative feature as in the example above left - there are several examples of very similar designs from the early-mid 18th Century from London and elsewhere. And of course if making an allegorical statue of Geology, then an animal skull is quite appropriate. The central figure above may represent Natural History, because as well as the skull of some ungulate, she holds a bunch of wildflowers. She on the right has a complete skeleton of some Eocene beast; click on the picture to see her companions, making a full representation of the Sciences.

This page was originally part of a 'sculpture of the month' series, for November 2016. Although the older pages in that series have been absorbed within the site, if you would wish to follow the original monthly series, then jump to the next month (December 2016) or the previous month (October 2016). To continue, go to the bottom of each page where a paragraph like this one allows you to continue to follow the monthly links.

Introduction to Church monuments // and to monuments in the churchyard and cemetery // and monuments with crosses // and allegorical sculpture

Visits to this page from 1 November 2016: 13,682