St Mary South Woodford, London/Essex - Monuments

South Woodford Church was mostly destroyed by fire in the late 1960s, but a fair selection of wall panel monuments survive; outside is a fine pillar to the Godfrey family and the tomb of the parents of William Morris.

The Church building

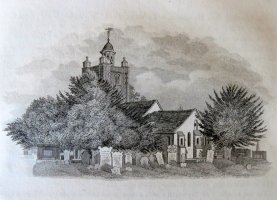

St Mary South Woodford is one of a group of about 20 interesting churches within ‘Essex in London’ – the area of Essex transferred to the metropolis in 1965, along with bits of other adjoining counties and the absorption and obliteration of ancient Middlesex. The medieval church – there is archaeological evidence it was founded in the 12th Century was long perished, being rebuilt during the 17th and 18th centuries, with the west tower being replaced in 1708. A rebuilding followed in 1817 and with additions later, and a fire in 1969 caused severe damage and led to the ruination of the interior and the 1708 tower being the oldest surviving part of the building, though the turrets are replacements dating from the end of the 19th Century.

St Mary South Woodford, 19th Century central frontage, modern aisles; and as it used to be.

The central Gothic entrance is flanked by uncomfortable modern blocks: better is the south side and porch surviving from the 19th Century, and where the tower, too short to be seen well from the front, is visible. Inside was gutted in the fire, and nearly all is uncompromisingly modern, the aim being to give an open, well lit space rather than retain any sense of what had gone before, bar a few panes of Victorian glass. What happened to the monuments inside the Church then? Various of them were taken from the old structure and put up in the 1817 one, but more were lost in the fire from the chancel (Robert Wynch, d.1590 and Jane [Wadnall] Mab, d.1616) and nave (Bridget [Ernie] Staples, d.1715, and Rowland Beresford, d.1719). What remains though is a good set of over a dozen wall panels, illustrating types from the late Tudor through to the mid-19th Century, with a single undecorated Edwardian tablet and a couple of modern slabs not noted here. The older ones are really rather good of their type, and five of the later ones are signed by their makers, including one by the illustrious sculptor John Bacon the Elder.

St Mary South Woodford, interior view with monuments.

Monuments

We take the surviving monuments in date order.

Rowland Elrington, d.1595, ‘Gentleman, late of London, Haberdasher and Merchant Adventurer’. A fine kneeler monument, showing many of the typical features. The deceased and his wife, Agnes, both wear bulky robes, with broad, high ruffed collars: they are rather elderly, he looking fairly ascetic, she rather grimmer, and wearing a hat with long cloth hanging behind. Their hands, which would have been praying, are lost. They both kneel on cushions, by fairly unbreakable convention carved with tassells at the corners. They face each other across a prayer desk (known as a faldstool), which bears two books conveniently aslant, resting on a tasselled drape. Above this stool is a painted shield of arms, surrounded by a thick border in the style known as strapwork. Above the figures is a great broad arch, so they are within a recess or niche, with a Roman S-shaped pattern around it. To the sides are broad pilasters (flat pillars) decorated with carvings in low relief of ribbons, panels bearing the couple's initials (RE and AE) and memento mori – in this case crossed bones and crossed spades and picks (grave-digging tools) with fruits and flowers. On top rests an oversize coat of arms, painted, within a strapwork circle, rather similar to a ship’s wheel, with supporting swirly strapwork at the base – very typical. To the sides are obelisks. Underneath, two shelves with a thin panel between, then the black inscribed panel flanked by shields of arms, and underneath all, a terminus of further strapwork and minor carving with central shield. The whole monument, typically for the period, is in a pinky-brown alabaster with gilt and paint. More on kneeler monuments here.

Kneeler monument to Rowland Elrington, d.1595, and his wife Agnes.

Elizabeth Elwes, d.1625, another kneeler monument, with the statue in the less usual front-facing position. As is conventional, she kneels on a tasselled cushion, her arms raised in prayer – the hands are gone – and wears the baggy, body concealing black-painted skirt favoured at this time. Her arms have thick sleeves, and heavy cuffs, and above, a large ruff frames the lower part of her broad head: as is generally the case, the sculptor depicts the deceased female looking as grim and unflattering as possible. Her grim, scowling face, with grey, swept back hair accentuating the rotundity of her face, is topped by a flat cap. To either side are flat pilasters supporting a shelf from which hang curtains, swept open to reveal the figure, and carved as looping around the pilasters. On top, with no entablature, is the pediment, open at the top to enclose a large cartouche, gilt and painted with the shield of arms. The inscription is on a black panel below, with carved borders. All in the favoured alabaster.

Elizabeth Elwes, d.1625.

Anna [Holbech] Melvil, d.1666, with a lengthy Latin inscription. Black inscribed panel, with an alabaster frame, side pilasters, and a raised top on which a painted shield of arms sits, within a cartouche. Behind this is a pediment and entablature, supported on two side pilasters. At the base, a thick shelf with mouldings, and underneath, a shallow apron with a carving of a winged cherub head and flowery wreaths, again all in alabaster. Another good piece, lacking a little from the top and base of the monument.

Later 17th Century: Anny Melvil and Richard Bayly.

Richard Bayly, d. 1694, erected by ‘his sorrowfull wife & executrix’, Bridget [Wayte] Bayly. This monument is in the form of a cartouche, which is generally a turtle-shell shaped panel with generous, sculptural surround, but in this example rather more rectangular than is normally the case. The individual elements however exemplify the type: the surround of scrolling and hanging drapes and a bit of Acanthus foliage, two winged cherub heads to the sides – though these are usually found higher up – knotted drapes at the upper corners. On top is a small coat of arms, painted, with a nice surround of carefully carved flowers, which form a roughly triangular hat to the piece. At the base, another central painted coat of arms, and a bracket at the base. Cartouche monuments are among the most ornate and beautiful of their period, a purely sculptural as opposed to architectural design type which is most frequently found from a little later than this piece.

David Bosanquet, d.1741, ‘Citizen and merchant of London’, with a Latin inscription. Damaged but still grand monumental panel in the best tradition of the times. The whole piece is in a grey and white marble with a pink hue which is likely discolouration. To the sides of the inscribed panel are two tall composite pillars, resting on a heavily dragooned [corrugated] shelf. To the right hand side stands the surviving one of a pair of naked cherubs, this one holding a cloth to his snivelling face and with one fat little foot resting on a skull, which is a memento mori (reminder of death); by convention, such skulls are often without the lower jaw, as here. Below, two brackets to the sides with a central curved apron bearing a cartouche of arms, now blank, and a beautifully carved terminus of clustered acanthus leaves. At the top, a curved, open pediment, which once would have enclosed some central feature, likely a large cartouche of arms. Characteristic of the period and with the carving on a generous scale.

Baroness Baltimore, d.1720.

Charlotta Lee, Baroness Baltimore, d.1720, daughter of Edward Henry, Earl of Litchfield, and wife of Benedict Leonard, Baron of Baltimore, and then of Christopher Crowe. A fine panel, with the inscription on the black panel usual at this time, a fine, broad frame of alabaster, and embellishments top and bottom. At the top, the painted coat of arms within a cartouche, and the remnants of two small flaming urns to left and right; drapes hang down to either side. At the base, within a circular frame of flowery carving, is a fine relief carving in Carrara marble of a mourning woman, wiping her eye with her drapery, and her arm resting on the funereal monument to her husband, a common pose at the time. The drapery she wears is complex and much folded, clearly to the delight of the sculptor, whose signature I did not see. The whole panel is pictured at the top of this page.

Obelisk monument to Drigue and Judith Olmius.

Drigue Olmius, d.1753, and his sister Mrs Judith Olmius, d.1749. A tall obelisk monument. The obelisk, occupying about three quarters of the total height of the monument, is in a beautiful variegated marble, quite unusual, and bears upon its top a carved wreath, and in front an attached urn, tall and bulbous with curvy handles, in a stained terra cotta colour. Under this elegant ensemble is the lower portion bearing the inscribed panel, a delicate oval, with border and surrounding field with generous scrolling above on either side of the painted cartouche of arms. The whole presents a colourful, precious-looking monument, with a feeling of lightness as opposed to the heavier panels accompanying it. An excellent conception.

John Bacon RA, monument to Charles and Elizabeth Foulis, 1783.

Charles Foulis, d.1783, and his wife Elizabeth Foulis, d.1782, erected by Robert Preston. In the form of a broad obelisk monument with figure sculpture [pictures of detail above, full monument at top of page]. The black obelisk occupies around three quarters of the total height of the monument, and has upon it a narrow-footed urn carved in relief with festooned flowers, resting upon a bulky plinth: it is this which bears the figure carving. A female figure in Roman dress sits in profile, cross-legged on some unseen chair; in her one hand she bears an Aladdin-style lamp, emitting copious fumes, and in her other hand she holds a slender branch. All this sits on a shelf with mouldings, above the low inscribed panel, which has a lower part in the form of an almost-semicircle. The text is very crisply cut. The piece is signed by the eminent sculptor John Bacon RA (called Bacon the elder, as his son was a prolific monumental sculptor too), known for his numerous memorial statues in various churches, including St Paul’s Cathedral and Westminster Abbey, and public statuary including the splendid group of George III and the River Thames in the courtyard of Somerset House in central London.

Frances Elizabeth [Dod] Selwyn, d.1800, wife of William Selwyn of Hoe Street Walthamstow, and Catheine and Thomas Selwyn, who died as infants. Old-fashioned panel with thin inlaid grey border, lower apron with painted shield of arms and two smaller devices to the sides. At the top, above a fluted shelf with mouldings, a further panel (with its own upper and lower shelf) referring to a sum of Five pounds, six shillings per annum left by will to be distributed in bread to the poor parishioners, 1815; although attached to the Selwyn panel, it does not actually say the bequest was from a member of this family.

John Popplewell, d.1829, his sisters Miss Ann Popplewell, d.1810 and Miss Rebecca Popplewell, d.1837. The panel is carved with a hanging drape over its top and sides, asymmetrical to give variety, and revealing a painted cartouche of arms above the inscription. This sits on a deep base carved with a pair of flaming torches crossed through a wreath: likely representing John and Ann Popplewell, and downward pointing to indicate life snuffed out. On a black backing panel. The monument is signed by a local stonemason, George Teague of Leytonstone. Decent white-on-black work, which dominated in the 1800s and through the early part of the 19th Century.

Anna Maria [Thornton] Vigne, d.1834, of Moggerhanger, Bedfordshire, and her husband Thomas Vigne, d.1841, and two offspring, Maria, d.1861, and Godfrey Thomas, d.1863. Plain white panel with curved top, on black backing panel of the same shape, signed by the stonemasons, Austin & Seeley of London. Felix Austin and John Seely were both statuaries in terra cotta and artificial stone, partners from around the time this panel was made, and with various works under their separate names usually from earlier dates – oddly each has his own piece in St Johns Wood Chapel.

Captain William Stanhope Stockley, d.1853, of the East India Company Service, and his wife Sarah, d.1889. Tablet with over-heavy pediment on top with a painted shield of arms. Two chunky curved feet below. On a shaped black panel, signed by the sculptor, Samuel Manning Jr of London. Rather appropriate to hang here, as Manning Jr was the son of the partner of John Bacon Junior, son of Bacon the Elder whose work we saw in the Foulis monument.

Colonel Godfrey Thornton, d.1857, of Moggerhanger House, Beds, erected by his sister. White on black panel, with upper shelf, on which is a sort of pediment bearing a shield of arms, little feet at the base. Signed by Bedford of 256 Oxford Street, a decent and prolific statuary throughout the 1820s-1850s.

Emla Josephine Westwood Burt, d.1909, simple panel with nipped corners, and quite nicely cut text. The only hint of the date is the somewhat pinky-grey cast to the marble, a favoured variety of the 1900s.

Also in the Church

There are no surviving features apart from the monuments. However, we may note:

A metal panel, perhaps iron, to Sydney Smith, d.1845, ‘reformist, wit and priest’ who was baptised in the Church in 1771, with a portrait in low relief.

A slate panel noting the rededication of the Church in 1972.

A few pieces of stained glass surviving from the early 20th Century (see picture below).

Outside the Church

The surviving monuments in the small Churchyard are significant,notably:

William Morris, d.1847 and his wife Emma Morris, d.1884, parents of the illustrious William Morris, Arts and Crafts worker, founder of the firm which produce so much excellent stained glass as well as much other ecclesiastical accoutrements; also other members of the family. Blocky chest tomb raised on two steps, with corner pilasters, acroteria above, a lid and draped pot. The monument is in front of the Church a little to one side.

A giant sarcophagus with lion feet, raised up on a chest tomb, to the side of the Church. A few bits of the inscription survive at one end, but the name is gone. See picture at top of page.

Peter Godfrey MP, d.1724, and family. At the back corner, left, of the Church. Grand pillar of veined pale marble, with Corinthian capital and an upper portion bearing a pot. On the tall base are carved shields of arms, and a damaged inscription, and the whole stands on steps made of massive granite blocks. Peter Godfrey had two wives, Catherine [Goddard], d.1706, and Catherine [Pennyman] d.1725 and although he had seven children, all died unmarried.

Larger monuments in Woodford Churchyard.

Martha Pelly, d.1797, and her husband William Raikes, d.1800, a seriously large mausoleum in the form of a box with curved roof, on which sits a full sized casket tomb, bearing the family arms carved in alto relievo.

William Hunt, d.1767, William Hunt Mickelfield, d.1826, Katharine Hunt Mickelfield, d.1842 etc, with arches all the way round and a complex roughly bell-shaped top, and raised on steps.

A couple of 18th Century headstones to the Ellis family, leaned against the wall of the Church, one with a pair of winged skulls (see picture at top of page, you will need to click to enlarge), the other with winged cherub heads and a pot, carved in relief. Typical of the later 18th Century.

A World War I memorial panel listing the fallen parishioners, also against the wall of the Church.

A variety of plainer tomb chests, mostly of the 19th Century, though notable is that to Patience Parker, d.1795, a grander tomb chest with gadrooned corners and a heavy overlapping slab on top. And by it, another ornate affair, with a central plinth bearing ovals which once held the inscriptions, protruding corners which may once have borne pillars, a top carved with festoons, and a nice funereal urn on top, perhaps of Coade stone given its excellent preservation despite its narrow base.

Tomb chests by the Church.

In front of the Church to the right, we must note an extraordinarily large copper beech tree, apparently of much renown.

And also to the front is a War memorial cross, bronze on stone, raised on a hexagonal base with steps.

Next to the Church is the Memorial Hall, put up in 1902, a nice mock Tudor structure of modest dimensions with a tall spirelet; on the gable it is noted that William Morris lived at Woodford Hall from 1840-47 – that building was demolished in 1900.

A stroll along the road to north and east passes a fine building, Electric Parade, built 1925, a building with a little clocktower dated 1890, and on the corner of the Woodford Green, a lone obelisk and a 1959 stumpy bronze statue of Churchill by David McFall (who made the two angel statues in St Bride’s Fleet Street) – the link being that this was Churchill’s constituency as MP from 1945-1964.

South Woodford Church's website is at https://stmaryswoodford.org.uk/stmarys-parish-church-and-woodford-history/.

South-West to Leyton Church // or South to Wanstead Church // West to Walthamstow Church // North-West to Chingford Church // Essex-in-London churches