Monuments in Enfield Parish Church, St Andrew

An atmospheric church with wooden, painted ceiling, wooden furnishings suitably dark,

screens in the arches, and many monuments.

The exterior as we approach from the road presents a good vista; the castellated Church has fortifications

on the short, square tower, along the Nave, and on the blocky south aisle which is towards us.

This aisle is in brick, as is part of the porch in front of it, while the rest is of stone and flint.

What we see is a mix of 14th and 15th Century and later. Thus the West Tower, characteristic of Middlesex churches,

is believed to be late 14th Century, says the Commission on Historic Monuments, the Nave of similar date,

the aisles of a 16th Century rebuilding, and the porch of the early 19th Century.

Inside, the aisles are seen to be of similar width to the nave, and chapels have been added on either side

of the chancel and altar, so the whole Church is rather broad, but there is no sense of being overly wide

because of the pillars and arches to nave and chancel. The chancel arch was painted in 1925 as a War Memorial,

and shows a crucifixion, angels and figures including a St George and the Dragon and St Andrew, of course,

in bright, light colours (if you like St George and the Dragon art, then here is a page of sculptures on this theme).

There are something over 30 monuments in the Church, plus brasses, including several important early monuments,

and a variety of later wall panels. As ever, click on the pictures to enlarge. We start with the grand altar tomb to Lady Jocasa Tiptoft,

dating from as early as 1446 this really is one of the most significant early tombs in Middlesex.

- Lady Jocosa [Joyce] Tiptoft, d.1446. An early monument indeed, as an altar tomb with Tudor arch and canopy above it such a superstructure cannot be as early as the mid-15th Century, and the Royal Commission on Historic Monuments says it is of later date than the altar tomb underneath, perhaps put up by Thomas Manners, First Earl of Rutland, c.1530. The monument occupies the whole width of one of the chancel arches, and can thus be seen from both sides. The sides bear diagonal panels, vigorously carved, painted, and enclosing painted coats of arms. Above, Gothic hexagonal pillars stretch thinly upwards, and the Tudor arch gives long, shallow spandrels (triangular spaces) containing shields of arms and fretwork carving of sinuous leafy vines. Above this, a row of gilded square devices of flowers etc, and a central large coat of arms with oversized helm on top and a bird, rather ruined, flanked on the top by a line of fretwork repeating devices, some sort of crocketing. The upper surface of the altar tomb bears a splendid brass of Lady Jocosa standing within a Gothic shrine, and wearing elaborate hairstyle and robes described by a modern guidebook (well, Late Victorian is modern for this website) as follows:

...A flowing dress deeply edged with ermine, which covers the feet, and over it an ermine surcoat, and

sleeveless jacket with a narrow border of ermine. Over all is a long heraldic cloak embroidered with the lions

of Powes and Holland, fastened by a a richly jewelled cord, the long ends of which terminate in tassels.

The head-dress is the large and elaborate horned coiffure of the time, bordered with jewels,

and surmounted with a coronet. Her hair is concealed by a cover-chef. A rich necklace with a pendant jewel,

narrow bracelets on her wrists, and a ring on the third finger of her right hand, complete the costume .

Lady Jocosa Tiptoft, d.1446, altar tomb and portrait.

Lady Jocosa Tiptoft, d.1446, altar tomb and portrait.

Lady Jocosa was daughter and co-heiress of Charles, Lord Powes, and co-heiress of the Most Hon. Lady March;

her husband was Sir John Tiptoft, Lord Tiptoft and Powis.

Robert Deicrowe, d.1586.

Robert Deicrowe, d.1586.

- Robert Deicrowe, d.1586 (though the inscription has a tiny bit of damage

and it could easily be read as 1580). A stone panel with low relief carving of a round arch resting on two Tudor

pillars, within which is the inscription panel, and on top of it, a carving of the deceased as a kneeler,

praying by his prayer desk (on this page for more on such monuments). Although somewhat damaged, we can make out his hair and beard, a ruff,

and that he wears a loose robe with long sleeves under some outer garment. He was a Citizen and Grocer of London.

The panel also commemorates his mother, Joane Deicrowe, and Robert Wheler.

- Bridget Harrington, d.1601, with a lengthy inscription.

The central panel has a wide stone border, with strapwork and mini-festoons of flowers etc, typical of its period

and good of the type. Strapwork cut out geometrical shapes based on squares, circles, crosses

and the like together with carved scrolls as part of the linear decoration, often with single stones or baubles

of a different colour inset, is a characteristic of many monuments up to the 16th Century,

petering out during the course of the first half of the 17th Century.

Dorothie Middlemore, d.1610, alabaster kneeler monument.

Dorothie Middlemore, d.1610, alabaster kneeler monument.

- Dorothie Middlemore, born Fulstone, d.1610, with two kneeling figures

facing each other over the usual prayer desk. The surround is rather square, in bold red-brown and pink alabaster

with black panels. To the side are rather plain pilasters, there are shelves above and below,

and the inscription panel is behind and above the figures, with on either side a carved hourglass and a skull

as memento mori. At the top of the monument is a shield of arms in a roundel surrounded by fretwork,

as in strapwork. The figure of the deceased is typical of the times: she is shown richly dressed with wide ruff,

headpiece, decorated dress and long skirts below. Her face is old, rather bald, and endearingly unflattering;

her arm thin under its sleeves. The statue of her husband, Robert Middlemore, facing her,

has a modern and disproportionately sized and placed head, seated directly on a ruff with an odd neck below

in what is a rather unfortunate restoration. The hands of both figures, which we would expect to be praying,

are instead downward turned in another fitful act of restorative activity, and his foot and the rear of his

cushion have also been replaced by someone not sure of what they were about. Anyway, the man wears rather

nice plate armour, and perhaps we should restrict our inspection to that and the female figure.

- Francis Evington, d.1614, an alderman of London. A kneeler monument,

with the deceased shown at his prayer desk, under an arch, as is typical. Corinthian pillars to the sides,

and above the entablature, a large coat of arms and two smaller ones forming a rough triangle and with its circles

and protusions, reminiscent somehow of the shapes formed by strapwork of a slightly earlier period.

The figure is bearded, with a large ruff, and dressed in an enveloping cloak with only his arms and hands showing. A picture

of the figure is at the top of this page, far right - click to enlarge.

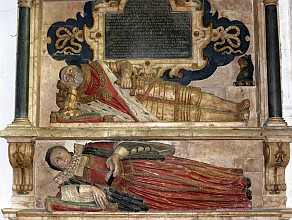

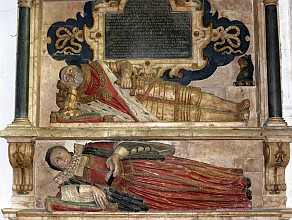

- Sir Nicolaus [Nicholas] Raynton, d.1646, and wife Rebecca Raynton, d.1640.

He was a great man in the area, the builder of Forty Hall and Lord Mayor of London,

and is commemorated by a grand Elizabethan monument with full figure sculpture and three stages,

comprising the two lying-down figures of the deceased, each on a separate stage, and kneeling figures

of their offspring below. Older monuments had their figures recumbent, lying strictly on their backs,

but somewhat after kneeling figures appeared in Tudor and Elizabethan monuments, statues like this pair appeared,

with the figure lying sideways, leaning on one elbow. The treatment at this time is generally stiff, with one leg

placed above the other, and the drapery hanging towards the feet rather than showing much effect of gravity,

as if the stiff figure had been standing up, laid down, and turned on its side.

These figures are well into the period, say 30 years after they came into general fashion,

and so the figure of Sir Nicolaus Raynton is shown with the upper leg a bit relaxed, and his ceremonial mantle

and chain of office pulled by their weight towards the base, but his wife is as free from gravity as ever;

look at the lines of her robe and sleeve of the upper arm. But this is all stylistic: let us look at the figures.

Monument to Sir Nicholas Raynton, d.1646, wife Rebecca, d.1640, and family.

Sir Nicholas Raynton is shown in full plate armour, beautifully carved, and holding the hilt of a vanished sword.

He has a magnificent ruff, with below it a broad chain carved with flowers and a portcullis, and a round pendant,

above a fur-lined mantle which covers his chest and trails down on his lower, left hand side

all these being the emblems of the Lord Mayor. He leans his head on one hand, the elbow of which is supported

on a tasselled cushion, just as Elizabethan kneelers have under them. Ancient knights would have heraldic beasts

at their feet, and Sir Nicholas has instead a dog, still rather heraldic and very furry, resting on a plinth

somewhat above his feet. The figure, in a richly honey coloured alabaster, is painted except for the plate armour,

and his face has somewhat ruddy cheeks, though we might expect that repainting has happened from time to time.

Portraiture is not a particular feature of most monuments of this date, with at best the sculptor

working from a painting of the deceased, but there is something of character to his face,

sombre and with perturbed forehead above somewhat heavy eyebrows. His face is rather rounded,

accentuated by the slight backward tilt of his head and the framing of his face by his beard and moustache,

and the skull cap on top. I rather like the treatment of his right hand, prominently holding the sword

and carved as the rugged hand of a strong man. He lies in a recess between free-standing Corinthian pillars

with dark marble shafts, and gilded rosettes carved on the ceiling above. Directly above him on the rear wall

of the niche is the inscribed panel, on black marble, with a compelx border tending to strapwork

and a shaped surround with complex ribbons; the panel has spandrels on which are winged cherubic heads.

Beneath Sir Nicholas Raynton is Rebecca Raynton, his wife, in a shallower stage little taller than the breadth

of her own shoulders. She is dressed in a red-painted dress tied at the waist with a cord and with long skirts

down to her feet, which peep out at the bottom, and as noted, with the gravity towards the feet

rather than vertically. This is certainly a custom rather than a lack of understanding of how drapery falls,

as a bit of her skirt rides up above one foot. Her ruff is broader and more splendid than her husband s,

and she has a short outer mantle and richly furred sleeves, the costume of the Lady Mayoress.

Her face again is round, with her hair combed backwards and around her head. She holds a small book,

perhaps a bible, open in one hand, and her other arm rests on her cushion. While as usual for such figures,

she is shown rather solid and in clothes that give no hint of her figure, the lightness with which she rests

on her cushion compared to her husband may be intended to indicate a delicate, more feminine figure,

and her hands have long, refined fingers.

Now to the the third stage below, in front of what is essentially an altar tomb to act as the base

for the older generation above. In the centre we have Nicholas Raynton (d.1641) and his wife,

also Rebecca, d.1642. As is usual for kneeler monuments, they face each other across a shrouded

prayer desk, with their children ranked behind them: boys behind the father, girls behind the mother.

There are two sons, in dress and pose miniatures of their father, but depicted as a young boy and a youth behind.

Ranked behind the mother are three daughters, likewise in similar position, the girl at the back being the

smallest and youngest. All are in unpainted alabaster, with just the heads, hands and cushions being coloured.

Nicholas Raynton, unlike his father, wears civilian garb including tunic, and some baggy garment below,

with an over-cloak which when standing, would fall to the knee. His wife has the usual long skirts

on a garment belted at the waist, full sleeves, and she wears a headpiece of light cloth which falls down her back.

We note that neither has the richness of Sir Nicholas Raynton above, and the broad ruffs and fur trimmings

to the cloaks are absent. In between the couple, resting at the base of the prayer desk, is a painted sculpture

of an infant, lying on two cushions, and swaddled in a blanket.

The top of the monument consists of a curved pediment, broken at the top to admit a large coat of arms

with knight s helm, copious scrolly feathers, and two rosettes with festoons of fruit and flowers.

Above this is an extra pit of pointed pediment, like a little roof, and coats of arms in cartouches

are on top of this and at the sides.

Martha Palmere, d.1617, monument and detail.

Martha Palmere, d.1617, monument and detail.

- Mrs Martha Palmere, d.1617. A wall panel, rather magnificent and original in design.

The inscription is on a black polished marble plaque, egg-shaped and gently domed, like a turtle shell,

and this sits within a broad frame of marble or alabaster, carved with figures. To left and right are standing

figures, very Baroque girls, long necked and bare-breasted, with complex, wavy drapery below,

sinuously turning inwards but with their bodies facing more outwards, each with a languid arm held up

across the stomach, and another, equally languid hand holding some accoutrement.

She on the left as we look at the monument is holding a crucifix on a ribbon, and at her feet is a pile of books;

she on the right holds some indistinguishable object, and has at her feet a pair of naked infants.

The girl on the left has had her face sheared off the statue, but she on the right shows a rounded, youthful

and soft face. Both have small wings, and the Royal Commission on Historic Monuments gives them as Faith and Hope,

with Charity at the top: this figure, wingless, is seated and looking upwards; she is more fully-dressed

than her sisters, though one shoulder is still bare. Again, what she is holding, though it may be a key,

is difficult to tell. Below her is a small egg-shaped coat of arms, echoing the larger piece below,

and to the sides of this are Cornucopias. At the base of the monument, an apron bears a female head

between festoons, with pendant corbels to the sides, and an inscription on a rectangular, framed panel below

bearing an epitaph. The important sculptor Nicholas Stone carved this excellent piece.

- Elizabeth Grene, d.1673, the eldest daughter of Sir William Myddelton,

son and heir of that Renowned Sir Hugh Myddelton, Baronet, who Brought the New River from Ware through this Parish

to the Cityes of London and Westminster . A dark panel in a pale marble frame, with a painted shield of arms

at the top.

- William Bolton, Marchant of London, and his wife Elizabeth Bolton,

and two daughters who dyed in 1665, the monument being erected by a surviving daughter, Elizabeth Bullock,

in 1674. A black panel with closely inscribed text with a rather plain frame, excepting the base,

which has an apron with carved scrolling and two small festoons of flowers.

This rests on top of the wall panel underneath, and there is nothing on top;

we may speculate that there may have been some upper ornamentation at one time too.

Elegantly carved cartouche to Henry and Barbara Dixon, end of 17th Century

Elegantly carved cartouche to Henry and Barbara Dixon, end of 17th Century

- Henry Dixon, d.1696, and wife Barbara, and noting his offspring

and that he was A Considerable Benefactor to this and Other parishes .

This surely has to be one of the most elegant cartouche monuments I have seen:

the central panel is almost violin-shaped, and the sides are two double scrolls, curling round and cone shaped,

with the widest parts being at the waist of the violin. The upper edge has two ferny fronds, and above this,

a smaller cartouche which would have contained a coat of arms but is now blank; this is flanked by

two freestanding winged cherubic heads. At the base, a thired winged cherubic head acts as a supporting corbel.

Excellent.

- John Watt, d.1701, Marchant of London, whoe gave a very Great and Bountifull Legacy

to the Hospitall of St Bartholomew s London, off which hee was a Governor. A very finely carved cartouche (a picture is at

the top of the page),

somewhat in the manner of wood carving by Grinling Gibbons, with deeply cut scrolls, flowers of a variety of types,

leaves and fruit, varied and inventive. The note of when he died and his age are added, as if an afterthought,

on a pendant shield with leafy surround below the main body of the monument.

Thomas Stringer, d.1708, with a fine bust.

Thomas Stringer, d.1708, with a fine bust.

- Thomas Stringer, d.1708, presumably a descendent of the Sir Thomas Stringer, d.1689, whose

fragmentary brass is noted at the bottom of this page. A monument with a bust of the deceased on a Classical base,

curved at the front, which bears the inscription, but the ensemble is actually dominated by the tentlike structure

above, with a great sweep of drapery from a canopy with festoons and bear s heads,

and low reliefs of crossed swords, a knight s helm, a wreath etc. Behind this is a blocky panel with an entablature

and pediment above, broken to insert a cartouche bearing a coat of arms, nicely carved.

Two architectural trophies are carved to left and right of the inscription, with strange shields and weapons.

The bust itself shows a young man, with Byronesque hair and a proud expression (close up at the top of this page; you will

need to click to enlarge), a neck swathed in tight collars,

and armour below. A fine sculpture, and a shame that no signature of the sculptor is visible.

- Stephen Riou, d.1740, Merchant of the City of London, erected by his only son,

Stephen Riou. At the bottom is added a later inscription to Maggie, wife [?] of Step[hen] Riou,

d.1771. The panel has an arched top, receding sides, and a heavy upper edging. Below, a wavy shelf,

then the deep apron with the second inscription, and curly brackets with carved clusters of grapes at their bases.

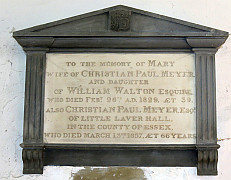

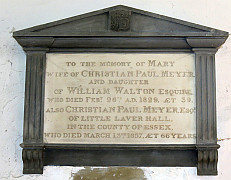

- Christian Paul Meyer, d.1790, merchant of London, his twin brother

Herman Meyer of Forty Hall, d.1832, and Christian Paul Meyer, his grandson,

d.1832. A plain tablet with an upper shelf on a rectangular black backing with two supports.

Obelisk monument to Mary Anne Keir, d.1820.

Obelisk monument to Mary Anne Keir, d.1820.

- Mary Anne Keir, d.1820, an obelisk monument with a fine example of carving of a girl leaning

on a pot, one of the most frequent and most admirable types of monument of the period. Thus the monument consists

of an inscribed panel, a dark, veined backing being blocky below, and obelisk shaped above, and in front of this,

resting on its own base, the white marble carving of the girl and the pot. She stands in conventional late 18th

or early 19th Century pose, leaning on one hand, elbow propped on the funereal pot, standing with legs casually

crossed, and wearing classical drapes, here so disposed as to leave one breast and one youthful, fair arm exposed;

the other arm has a rolled up sleeve to leave it bare from just below the elbow. She also wears a hood of drapery

which frames her head and bare shoulder. Her face is well sculpted, with powerful lines to the jaw and neck,

and the arm, as said, is good, but the rest is somewhat awkward what is the shape of the torso under the robes,

with the waistless solidity, or the rather short legs twisted so one foot is pointed directly forward,

the other at right angles try standing like this it is possible, but certainly not comfortable.

Note the downward pointing torch she carries, symbolising the snuffing out of life, and the delicate carving

to the pot.

- Revd. Harry Porter, d.1822, Vicar of the Parish and fellow and tutor of Trinity College

Cambridge, regular, zealous and unremitting in his addresses from the pulpit . In a Tudor Gothic style,

thus the inscription is the centre of a square surround with clustered columns left and right, the typical broad,

pointed arch of Tudor times, and a fretwork of repeating leaves as a balustrade; open coronets are left and right.

Altogether it recalls some ancient gate such as that to St James Palace, and this is heightened by the Portcullis

carved above. The work is signed by Bossom of Oxford.

Revd. Porter and Mary Meyer monuments, 1820s. Tudor and Classical designs.

- James Meyer, d.1826, of Forty Hall. A classical monument with a pediment above

three capitals which are on a sort of entablature which sits upon the inscribed panel with no columns or pilasters.

Below the bottom shelf is a careful carving of a sea shell, surrounded by seaweed fronds, on a scroll.

All on a shaped black backing. Signed by the stone mason, Hobson of Enfield.

- Families of Benjamin Boddington, d.1791, and Thomas Boddington,

d.1821, including members through to 1828. Benjamin had three wives, and Thomas had eight surviving daughters,

and many of both families died young. The panel is closely inscribed with text, with room for more family members

at the bottom, left blank though Samuel Boddington, d.1843, has a separate monument in the Church (see below).

The narrow, rather delicate border has pilasters at the sides with Egyptian capitals, a fluted top, and a wavy base.

- Mary Meyer, d.1829, and husband Christian Paul Meyer,

d.1857, a white panel with heavily cut inscription, within a Classica surround of grey marble:

fluted pilasters, pediment with no entablature to speak of above, bearing a coat of arms, and beneath,

two brackets.

- Henry Carrington Bowles, d.1830, and wife Ann, d.1812,

erected by their eldest son in 1832. As a tomb chest end, with on the lid a coat of arms with swirling acanthus

leaves on either side, and on the base, a double wing ornament in relief. Little flowers and circlets complete

the monument, which is on the usual black backing.

- John Abernethy, d.1831, a surgeon who achieved some fame with a book on the origin

and treatment of diseases. The inscription is firstly in Latin, and then continues in English,

with added inscriptions to various relatives through to 1855. Rather a severe monument,

consisting of a white panel, or rather two joined ones, with a dark fram around with some architectural mouldings

and lion s claw bases to the upper pilasters, but no other ornament. Beneath this is set in the wall

a small cartouche with painted coat of arms (picture at top of page).

- James Farrer Steadman, d.1834, and wife Anne, d.1865,

who later married William Everett, and their attached friend , Carloine Lee, d.1872.

A crisply cut Classical monument in white marble, with side pilasters with rosettes on the capitals,

an upper shelf with receding plinths upon it like a fireplace, on which stands the base for a

severely classical urn with a flame coming out of it. On the base are carved two crossed palm leaves.

At the base, a lower shelf beneath which is an apron with a coat of arms behind which is a single palm frond;

small supports are to either side. The whole is on a shaped black backing.

- Samuel Boddington, d.1843, a steady supporter of civil and religious liberty,

to refined taste in literature and the arts , erected by his daughter Gracy Lady Webster.

Pale stone Baroque monument, the central white marble panel having a frame, upper curved pediment

enclosing a shield of arms and ribbon with motto, curly side pieces (lyres), a heavy base, and two carved brackets,

also large.

Maj.Gen John Martin, with sculpted relief by M.A. Edwards.

Maj.Gen John Martin, with sculpted relief by M.A. Edwards.

- Major General John Martin, d.1852, who fought in the battles of Talavera,

Quatre Bras and Waterloo, a white and black monument, with a relief plaque showing a figure group of the deceased,

shown as a youthful Greek hero, collapsed on the back of a figure of Mercury bearing him aloft while a girl

rests her head in mourning on his shoulder. Rather nicely composed, and rather downplayed by the inscription that

This unpretending tablet, as a small tribute of affection and gratitude, is erected by his godson and heir,

Alfred Plantagenet Frederick Charles Somerset . The stonemason was M.A. Edwards of St George Street,

Hanover Square.

- Daniel Harrison, d.1873, a local magistrate. Carved as an unrolling scroll,

not in itself unusual in 19th Century tablets, but in an unusual way, thus the bottom with a roll,

and the top tied at the centre to a small wreath, and thus rolled separately on each side, with a little carved

ribbon above the inscription. A thick shelf is below, with two supporting brackets. On a shaped black background.

- Agnes Sarah Adams, d.1889, as a tomb chest end, with shelf, lid or pediment

bearing carving of crucifix, chunky base and little legs, on a rectangular black backing.

It is by Gaffin of Regent Street, among the most prolific of stonemasons,

and this is typical of their well-executed but extremely plain monuments.

- Warwick William Robinson, d.1915, killed in action at Festurbert,

a plain marble panel with a small crucifix.

- Lieutenant Arthur John Smith, d.1915, killed in action at Loos, Flanders.

A Gothic window tablet, with side pillars in dark marble, attached, a grey outer backing,

and the rest of the monument in bright white. Really rather late for this sort of monument, and very nicely done.

Late Gothic tablet to Lieut. A.J.Smith, d.1915.

Late Gothic tablet to Lieut. A.J.Smith, d.1915.

There are several brasses in the Church aside from the Tiptoft one, some just plain text, others more decorated.

We may note:

- William Smith, d.1592, and wife Jane,

two figures turned towards each other. William Smith, presuming it is he, is shown in full length robe,

with ruff and collar; Jane is a shorter figure wearing robes and a hat; both are praying. He served

King Henry VIII, King Edward VI, Queen Marie, and Queen Elizabeth.

- Sir Thomas Stringer, Knight, d.1689, Serjeant at Law to King Charles II etc.

There are texts to others of the Stringer family.

- Jane Hotchkiss, d.1803, has a highly decorative surround, with pillars and figures,

male and female, and above, a sunburst behind a pot with trumpeting angels to the sides,

rather gruesome but most spirited in execution.

- A modern brass to Sarah Ann Hunter, d.1885, in the common style of blackletter text

with a few capitals in red, and a border, in this case unusually ornate with a repeating somewhat Celtic pattern

of chains and quatrefoils and stylised flowers. In addition, on the left hand side is a small relief portrait head

of the Mrs Hunter. Below it is a coat of arms in heraldic colours, with two lilies above.

- George Hewitt Hodson, d.1904, Vicar of Enfield, with broad borders,

much decorated, and a large inscribed crucifix.

Commemorative mural to WW1 on the Chancel Arch.

Commemorative mural to WW1 on the Chancel Arch.

Among the other decoration of the Church, attention should be drawn to the painted chancel arch,

with Crucifixion and attendant figures and angels, which commemorates the 1914-18 War.

All in all, this really is a church to make an effort to see for all those interested in sculpture and monuments.

Corner of interior with brasses.

Corner of interior with brasses.

Around the outside of the Church are various well-cared for monuments, including some tomb chests from the

18th and 19th Centuries. Perhaps the best is the heayy casket tomb to Samuel Garnault, d.1827,

Treassurer of the New River Company, and Samuel Carver, d.1841. The casket bears carvings of upturned torches

in relief, symbolic of the snuffing out of life, aas well as the remnant of the heraldic shield of the family,

and light relief swirls on the edge of the lid above. There are a couple of carved coats of arms from vanished

monuments set into the Churchyard wall, and among the more usual gravestones, among other relief ornamentation

are two or three with skulls.

Casket tomb to Garnault and Carver, mid-19th Century.

Casket tomb to Garnault and Carver, mid-19th Century.

With many thanks to the Church authorities for permission to show pictures of the monuments inside; their website is

http://www.standrewsenfield.com/index.php/22-useful-information/21-st-andrew-s-history.

Top of page

Monuments in some London Churches // Churches in the City of London // Introduction to church monuments

Angel statues // Cherub sculpture

London sculpture // Sculptors

Home

Visits to this page from 25 July 2014: 8,350

Lady Jocosa Tiptoft, d.1446, altar tomb and portrait.

Lady Jocosa Tiptoft, d.1446, altar tomb and portrait.

Elegantly carved cartouche to Henry and Barbara Dixon, end of 17th Century

Elegantly carved cartouche to Henry and Barbara Dixon, end of 17th Century

Late Gothic tablet to Lieut. A.J.Smith, d.1915.

Late Gothic tablet to Lieut. A.J.Smith, d.1915.

Commemorative mural to WW1 on the Chancel Arch.

Commemorative mural to WW1 on the Chancel Arch.

Corner of interior with brasses.

Corner of interior with brasses.

Casket tomb to Garnault and Carver, mid-19th Century.

Casket tomb to Garnault and Carver, mid-19th Century.