St Michael Cornhill Church - Monuments in 10 Minutes

A 10-minute look at the monuments in the City of London Church of St Michael Cornhill. The Church contains around 40 panel monuments, including a good group of 17th and 18th Century pieces, and numerous simpler 19th Century panels The distinctive Church tower is by the architect Nicholas Hawksmoor.

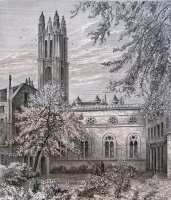

St Michael Cornhill.

This page is for visitors who have only a brief time to see the Church and its monuments. When you have more time for a longer visit, see this much fuller description of all the monuments.

The church of St Michael Cornhill was built (though maybe not designed) by Christopher Wren in 1669-72, the tower put up in two stages rather later from 1715 (Hawksmoor built the upper levels), and as the Church is boxed in by other buildings, it is this tower that is what we see, together with the ornate Victorian porch onto Cornhill. Inside, the Church is of a basilica design, with Tuscan columns separating aisles from nave, and high vaulted ceilings. The monuments we are interested in mostly hang in groups in each bay, some rather high up.

The collection is fairly large by City Church standards, over 40 monuments in all, though a few are absolutely plain. We have seven from the latter 17th Century, six from the 18th Century, a couple of dozen from the 19th Century including numerous white-on-black panels, and a wooden 20th Century piece. Click any picture to enlarge, or hover for caption.

John Vernon, d.1615

The earliest monument, to John Vernon, d.1615, includes his portrait bust, a forward facing half-figure, somewhat balding, with a moustache and a contemplative expression, enhanced by the posing of his hands, one to his breast, the other resting on a skull, emblem of mortality and death (lots more skulls on this page). He wears a broad ruff and a fur lined cloak.

Later 17th Century.

Look out for these two other early panels with rounded outlines and winged cherub heads, one to Francis Mosse, d.1657, and his son Henry Mosse, d.1676, 'Masters of the company of Scriveners & Deputys of this Ward’, and the other to Luke Nourse, d.1673, Hugh Wells, d.1673, Citizen & Armourer of London, and Edward Nourse, c.1689, Cit.[izen] & Girdler. This second piece is a cartouche design, with a curved, slightly domed central area with the inscription, a border of scrolls and foliage, and three winged cherub heads. Lots more winged cherub heads on this page.

Cowper monuments (click to enlarge, hover for caption).

In the corner of the Church, separated off by glass doors, are two grand monuments to the Cowpers. Sir William Cowper, Baronet, d.1664, and his wife Martha [Master] of East Langdon, and their fourth son, Spencer Cowper, d.1676 is a big 17th Century panel, with jawless skulls, polished marble Ionic columns, and leafy scrolling - perhaps the work of the sculptor Jaspar Latham - picture above left. And close to this is the biggest monument in the Church, to Sir Edward Cowper, d.1685, a grand mass of marble rising from the floor with fantastically twisted pillars and strikingly coloured marble. Perhaps by the sculptor Thomas Cartwright Senior, another of the sculptor-masons working on Wren’s City Churches.

Later 18th C: Cowper and Helmsley.

On to the 18th Century panels, and a wider variety of shapes. We pick out two: firstly another of the Cowper family, Sir William Cowper, d.1706, but the monument erected in 1759, distinctively shaped with a hanging drape, a curly pediment, and a thin-stemmed egg-shaped pot, within a roundel. He was a 'Baronet of Great Britain and Nova Scotia' And of similar date, the colourful monument to Timothy Helmsley, d.1765, Citizen and Mercer of London, and his sister Catharine Muskett, d.1756, typical of lighter style polychrome monuments of the period.

The cherub warming his feet (click to enlarge).

On to the 19th Century, and we start with the cherub warming his feet, carved on the hanging-drape monument to John Platt, d.1787, and his wife Ann Platt, d.1802. Signed by one of the Westmacott dynasty of sculptors. Lots more about cherub and putti sculture on this page.

Obelisk monuments: Perriman and Clay.

As alluded to above, white-on-black panels are the predominant style of the earlier 19th Century, and among these, obelisk monuments are a distinctive group of their own. Here we have a short stubby obelisk on the monument to Felix Clay, d.1828, with a carved pot above above a neatly carved tomb chest end design - it is by a skilled monumental sculptor called Humphrey Hopper, who carved an unforgettable mourning girl for the J.H. North monument in Harrow on the Hill Church. The second piece shown above is a more ambitious white-on-black piece, to Thomas Burne, d.1812 and his wife Elizabeth Burne, d.1778: we have emblematic figures of Faith and Charity (see this page for more statues of Charity). By the sculptor J.G. Bubb, who carved figures standing on the grand Nash terraces around Regent’s Park. Spot the small snake swallowing its tail (click picture to enlarge and see it) at the top of this monument, rather pagan symbology for the Church, but common enough on monuments (see this page for more about use of snakes in sculpture).

William Richardson and family.

19th Century minor carving: Wrench, Maund and Richardson.

Among many more 19th Century panels, we pick out three with some carving. Above left is the panel to Thomas Robert Wrench, d.1836, Rector for 42 years, his wife Sarah Wrench, d.1835, and their son Jacob Wrench, d.1837 - this is Victorian revival Gothic, with thin columns, pinnacles and a battlement. Centre is a casket tomb to W.H. Maund, d.1838, with outward leaning sides, pointy lid and acroteria ('ears') to the sides, and by a fairly widespread convention, carved lion’s feet below. And to the right, we have William Richardson, d.1810, his wife Ann Richardson, d.1827, and their daughter Ann, d.1860, when the monument was clearly made. It is a typical example of a more ornate mid-Victorian design, the pillars with leafy capitals on thin shafts, the foliage of Gothic form but carefully symmetrical.

Among various furnishings in the Church, the unmissable one is the the Pelican feeding its Young near the entrance, made of painted wood, a vicious palaeolithic creature with hooked beak and cruel gaze, surrounded by its brood of four young, avariciously pecking at their mother’s breast for blood. The church explorer will see many pelicans feeding their young - but not another one like this.

The Pelican feeding its Young

Outside, notice the sculpture above the porch door of St Michael striking down Satan, bu the eminent Victorian sculptor J. Birnie Philip (who also carved the angels inside the Church high up on the walls), and down St Michael's Alley is a small churchyard, giving the only external view of the late 17th Century body of the Church.

Remember, if you have time for a longer visit and want more about the monuments, see this page.

Just down the road is St Peter Cornhill, with a more modest collection of monuments, and excellent woodwork.

And the Church's own website is at https://www.st-michaels.org.uk/our-history/.