Monuments in St Bartholomew’s Wednesbury, Birmingham

Wednesbury Parish Church has about 25 or so monuments, with three from the 17th Century, including a great tomb chest

with carved statues and a ‘kneeler’ monument, a couple from the 18th Century, one of which is a characteristic obelisk monument,

and a goodly number of 19th Century plaques,

showing variations on the Classical tablet, and a few Gothic ones. Among the 19th Century collection are several by

William and Peter Hollins, Birmingham’s most notable tomb sculptors,

including with figure carving and a bust. There are two monuments from the early 20th Century,

characteristic of their period. Thus in this one church we get a little potted history of Church monuments of the Birmingham area.

17th Century monuments:

Monument to Thomas and Elianor Parkes (he d.1602).

Monument to Thomas and Elianor Parkes (he d.1602).

- Thomas Parkes, d.1602, and wife Elianor; he was ‘his Countries lover, Churches beautifier and

poores benefactor’. With a Latin inscription; odd to have a combination of English with Latin on one inscription.

The plaque is oval, within a rectangular cartouche in alabaster with an inner black border. On each side are kneeling figures

in high relief: Thomas Parkes on the left, Elianor on the right, facing each other. They are both in profile,

so we see exactly one praying hand and no hint of the other, but while her face is strictly in profile,

his looks slightly outwards, thus we can see both eyes and have some impression of the full face, which shows a broad-foreheaded

man with heavy full beard and moustache. Both wear large ruffs, and black painted, many-buttoned shirts;

he wears an over-cloak with fur-lined border, a common accoutrement, while she has a dark robe not distinguishable from her skirt.

Their feet are covered by their robes trailing over the edge of the pillows on which they kneel.

Underneath the main field, a broad plaque shows their children, who as customary, have the male offspring under the father.

They comprise two small kneeling bearded figures rather similar to the father, and an infant swathed on a cot;

there is no symbol such as a skull indicating the infant was deceased, though there is a Tudor rose above,

but given the age of the other sons, we must assume he did indeed perish. Facing them on the other side are three girls,

who by their slender figures (compared to the lumpish figure of the mother) are rather younger than the male offspring.

Each wears a bonnet and ruff, and has a wide skirt, and all rest on pillows. Between, in the centre, is the remains of perhaps

a cartouche which would have borne a coat of arms. The rest of the monument consists of an alabaster base

decorated with square panels, cut out in a variety of simple geometric shapes, and around the two principal figures,

a frame made of square pilasters and an upper entablature. The whole edifice does not protrude much from the wall,

but the impression is of a tomb chest with a three dimensional monument upon it, a grand and noble thing.

Monuments like this, with a pair of kneeling figures, husband and wife, epitomise the typical Elizabethan and

Jacobean era monument on the larger scale (see this page). They tend to be full statues in the round, or attached ‘three quarters’ statues

rather than in high relief as here, so in this respect the Wednesbury monument is unusual, but in all other respects

they are characteristic of the kneeler type.

Richard Parkes (d.1613) grand tomb chest with effigies.

Richard Parkes (d.1613) grand tomb chest with effigies.

- Richard Parkes, d.1613, ‘that worthie, generous and generall labourer (much wanted and lamented)’,

a massive alabaster tomb chest with two carved figures lying upon it. This is a significant early tomb,

and the figures are extremely good of their type. The effigy of Richard Parkes shows him with receding hair,

bearded, and with a Greek nose. He wears long robes, with no apparent effect of gravity, though he lies upon a pillow,

the tassels of which do. His wife wears a close head covering so we cannot see her hair, and atop this a hood,

with a ruff below framing her face. Her arm lies across her body. The tomb is set against a wall, and the inscription is in a panel

with a black border on the outward facing side of this. Next to it, we have the children of the family: to the left, two girls,

seated praying, and as is normal, very similar to each other, each sporting a tall mound of hair, a wide collar,

and a black robe. The one in front has a prayer desk with open bible. On the right hand side are two kneeling boys,

shown rather young, and behind them a stack of four swaddled infants, presumably deceased offspring.

The two boys rest on red-painted tasselled cushions (the girls’ long skirts hide theirs), and again,

the one in front has a bible and prayer desk. The scene includes a stylised flower in a roundel on each side,

and a sun carved in low relief above. At the head end of the chest tomb, obscured by a cupboard,

is a large, solid coat of arms, with typical accoutrements on the visible side: tall staffs with encircling ribbons,

an hourglass, and crossbones. Such grand monuments with recumbent effigies are really rather rare even in the great Cathedrals,

so we are lucky to have one to see in Wednesbury. See also pictures at top of page, far left and right (you will need to click to enlarge).

Francis Wortley's crest, with peacock.

Francis Wortley's crest, with peacock.

- Frankus Wortleius de Wortley, 1636. Plaque in frame, stained and darkened from its original,

presumably white state, with Latin inscription. It records the saving of Wortley’s life by some unnamed person,

presumed to be a certain Walter Harcourt, whose memorial plaque was originally beneath the Wortley tablet,

when this was located in the chancel. The frame consists of two thick square pilasters, bulky at base and capital,

an upper and lower plainer frame, all these being somewhat darker than the central plaque, but perhaps just more stained,

with a small appendage above each pilaster. In between, detached from the monument, is a free-standing coat of arms,

upon a roughly square backing carved as a piece of fabric with many small folds all emanating from a knight’s helm above;

this helm is crowned, and upon it is a simple but spirited carving of a peacock. Below the capitals of the pilasters are the

initials G. H. Presumably all this is the surviving remnant of some more ornate tomb.

18th Century monuments:

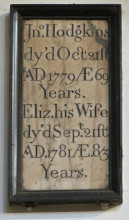

Memorials to Jesson and Hodgkins, 1770s.

Memorials to Jesson and Hodgkins, 1770s.

- John Jesson of Walsall, d.1774?, and wife Ann, d.1763, and son John, d.1782, and daughter Ann.

It is an obelisk monument, and the inscription, on a black panel, has side pilasters, an entablature above supporting a shelf,

and above this, a tall black panel cut to the shape of the obelisk or extended pyramid.

This has upon it a white marble cherubic head, winged, with a nice patterning to the feathers.

To left and right of the obelisk, above the pilasters, were once two small pots or finials, of which only one remains in place.

At the base, a curved apron between side brackets, with a rounded bracket in the middle.

This is a good and typical example of an obelisk monument, and dates from the period when they were most plentiful:

there are a number of them in St Philip’s Cathedral in Birmingham, itself a former Parish Church.

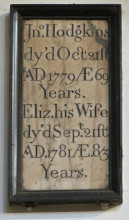

- John (‘Ino’) Hodgkins, d.1779, and wife Elizabeth, d.1781, written in condensed form,

in a plain black frame (see picture above). A minimalist monument, and not at all usual. Perhaps it is just the centrepiece of a larger monument

which has not survived, but the setting of the text would likely have been more spread out were that the case,

so this may well be all there ever was to this monument.

Works by the sculptors William and Peter Hollins:

Monuments to Edward Crowther, Mary Addison and Samuel Addison, the work of Peter Hollins.

As we move to the 19th Century, we start with the work of Birmingham’s most illustrious monumental mason and sculptor family,

that of William and Peter Hollins. William Hollins (1763-1843), the father, was a significant architect of Birmingham,

though his known works do not seem to have survived, and was also a sculptor and monumental mason whose work may be found

across the Birmingham conurbation (see this page). His son, Peter Hollins (1800-1886), was an extremely gifted sculptor

whose work is far more widespread. There are several examples of their work in St Bartholomew’s:

- William Holden, d.1806, a Birmingham merchant, and wife Mary, d.1752 –

so he was over 50 years a widower – and son John Rose Holden, d.1827, and his wife, also Mary, d.1829.

The son was sometime Rector of Upminster, Essex. In small capital text on a panel styled as the front of a tomb chest,

with low lid, anemone acroteria, and on the top, a cut and withering leafy branch. Below are short legs and a chunky basal shelf,

and the whole thing is on a black rectangular backing. It is signed simply ‘Hollins, Birm[ingha]m’ and the date makes this

William Hollins, the father.

- Edward Crowther, d.1822, and Stephen Falknor Crowther, d.1829,

brothers in a partnership of solicitors practising in Birmingham. The panel supports an agglomeration of a small lamp,

centre, relatively large acroteria carved in low relief, drapery over everything and branches with leaves and berries,

perhaps hawthorn, in front. A single drooping flower hangs over the front of the panel below.

Together, the overall shape is of a pediment, but the leaves and drapery allow a pleasing asymmetry in the detail,

and the carving is excellent. Under the panel, a recessed base with a low relief repeating pattern, and little corbel legs

at the corners are carved as stylised flowers. Signed Hollins, Birm[ingha]m. Gunnis, the sculptural historian, gives it to

Samuel Hollins. As draped pot monuments go, there is rather more drapery, and rather more variety to the drapery, than is usual,

and this is a characteristic of the work of Samuel Hollins,

who delighted in carving ornate and complex folds and hangings in their own right.

- Mary Addison, d.1796, and sons William, d.1796, an infant, Samuel, d.1817, and John, d.184(?)0.

The inscriptions on the base of a marble monument, bearing an accomplished sculptural group,

consisting of a seated mourning girl in front of a pot with a high relief male portrait.

She is dressed in classical robes down to the ankle, but cut with short sleeves, and light enough in weight to show the lines

of the figure underneath. The drapes have several sets of interlocking repeating folds, with the sculptor showing an obvious

interest in this aspect of the composition. She is young, Classically perfect, with long, elegant arms and delicate hands,

and a charming nearer foot in a light sandal (see picture at top of page). We can only think that we are seeing the deceased, Mary Addison,

but who is the portrait on the pot of? Presumably the last son, John, who was a banker, as there is a pair of scales

in front of the pot, an accoutrement of a money-counting banker. Behind the figure is a tall plinth, with curved pediment

on top bearing a coat of arms, ribbon, with one side lost, and a summit rearing horse. This subtle and excellent work is signed

by Hollins, Sculptor. If this was indeed done in or after 1840, then this would presumably be Peter Hollins.

A charming work, somewhat reminiscent of Flaxman,

though he would not have done his drapery like that.

- Samuel Addison, d.1849 with a lengthy inscription noting that ‘As a banker for nearly half a century

in this town he was cautious, considerate, successful; as a magistrate he was impartial, patient, just;

as a citizen he was loyal, courteous, upright’ and listing his varous charitable works, including aiding the rebuilding of the Church.

Another significant monument by Peter Hollins, with the inscription on the side of a casket in high relief,

with decorated top, covered in rather symmetrical drapes which hang down behind to the sides,

carved lion feet underneath, a common enough accoutrement, but here shown sideways rather than the conventional forward-facing

aspect. All this rests on a series of stepped shelves. To the right of the casket as we look at it stands a figure of a

young angel, standing facing the casket, one arm raised, but unfortunately with the hand missing.

He wears the lightest of drapes, and much attention has been paid to the delicate modelling of the limbs and face.

The whole on a black backing panel, and with above the casket, a small cartouche of arms with the self-explanatory motto:

‘Prudentia et Honore’.

- Charles Adams, d.1854, with the panel as the base for a headstone cut at the top to form a chunky curved pediment,

in front of which is a casket in high relief. This casket is asymmetrically draped, the folds of cloth hanging generously

and elegantly down to the sides, and on its lid is a wilting tree indicative of death;

it has an unusually large number of leaves, and the sculptor seems to have rather taken to the carving of this element

of the memorial. The whole edifice is supported on two legs on a lower base, very solid, which bears the signature of the

sculptor, ‘Peter Hollins, Sculptor, Birm[ingha]m’.

- Revd. Isaac Clarkson, d.1860, Vicar of Wednesbury and fundraiser for the Church, with long inscription,

and above, a fine bust in a niche. He is shown in late middle age, with a purposeful look, a stern, serious man,

and wearing a heavy cloak above suit and cravat – this garb nicely giving something of the modern, while preserving

a sense of Classical decorum. This is the last work in the Church by Peter Hollins,

and is a good example of a mid-Victorian monument with a bust, following directly in a tradition of monuments with busts

dating back to the later 17th Century. A separate wall plaque cut in the shape of a headstone notes that

Revd. Clarkson presented the font and a new clock for the Church in 1856.

Bust of Isaac Clarkson, by Peter Hollins.

Bust of Isaac Clarkson, by Peter Hollins.

Other 19th Century monuments:

- Joseph Hobson, d.1802, and wife Elizabeth, d.1817, as an obelisk or tall pyramid,

with a flower carved on the top, a fluted base with three stylised smaller flowers in circlets, and two brackets,

carved as wavy leaves. The text is extremely elegantly cut, and though the obelisk is of conventional shape,

the monument as a whole is not one of the usual types.

- Thomas Rolinson, d.1824, who left £100 for the benefit of the poor in Wednesbury,

stipulating that it should be ‘to the churchwardens for the time being in trust to invest the same on Government

or real security or securities at interest to apply and expend such interest in the purchase of bread’.

With an upper shelf, acroteria, and a pointed top with upon it a wilting branch, rather sparse of leaf.

The wilting branch, already noted as a symbol of death, was fairly popular at this time.

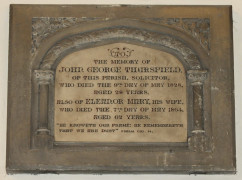

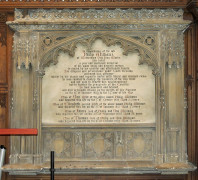

Thursfield and Williams monuments, 1820s, the humble and less humble ends of Gothic.

Thursfield and Williams monuments, 1820s, the humble and less humble ends of Gothic.

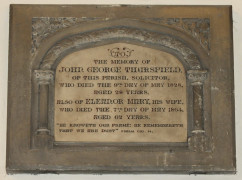

- John George Thursfield, d.1828, solicitor, and wife Mary, d.1864.

Modest marble tablet, as if the top of a Tudor Gothic window, with heavy stone surround, including pilasters

(thin ones, as we are Gothic here), a string-course type band over the top with Acanthus leaves,

two spandrels filled respectively with Acanthus and a couple of flowers, and some vine, again with a flower,

carved in relief, and a plain outer frame. Unusual, and the first of our Gothic examples in the Church.

- Francis Wastie Haden, d.1828, with a long inscription, rather tightly written in capitals,

noting inter alia that he was in the Peninsular War under Wellington with ‘officies of high trust and responsibility’,

Chief of the Commissariat at the British Settlement of Nova Scotia, then in the same role in Gibralter.

As a panel with upper and lower shelf, small blank pediment and acroteria (‘ears’). Behind the pediment

is a base supporting a pot with a drape upon it. Little feet as bell-shaped flowers, and a central coat of arms.

All on a black panel. It is more unusual than it sounds; the main panel is slightly tapering towards the top,

the acroteria are unusually placed, and the drapery on the pot looks almost stuffed in the top.

It is signed by Baker of Liverpool. There were in fact two Bakers of Liverpool, Benjamin Baker being the father,

and John Baker the son, trading at marble masons under the name ‘Benjamin Baker and Son’ until they dissolved their partnership

in 1844, having already had a bankruptcy in 1839. The firm was prosperous in the 1810s, when Benjamin Baker is recorded

as giving stone to Newington Chapel in Renshaw Street, Birmingham, for its beautification.

- Revd. Alexander Bunn Haden, d.1829, Vicar, and wife Mary, d.1837.

Tablet with border and upper shelf, on which rests a borderless pediment, or a triangular shape a bit higher than a pediment,

bearing scrolling, a scallop shell and a small ribbon with motto and a heraldic appendage – an upside down knight’s leg

with a spur. At the sides of this pediment are two rather large acroteria, nicely if simply carved.

The whole is on an almost square black backing, and has two small brackets carved as stylised flowers.

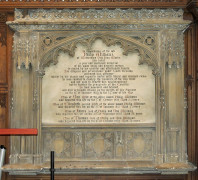

- Philip Williams, d.1829, wife Ann, d.1808, second wife Elizabeth, d.1821,

and two offspring d.1830 and 1839, in blackletter with some red capitals, in a style popular rather later in the 19th Century

on brasses, the panel being encased in an elaborate Tudor Gothic surround, with tracery at the top including a series of trefoils

and cut-out spandrels, an upper border with a low relief carving of some vine, and more tracery above.

Below, a deep base bearing three panels carved with quatrefoils, as if a tomb chest, and to the sides,

empty Gothic niches with crocketing etc above and to the sides, and clustered pilasters.

All rather Puginian, and characteristic of a better class of Gothic monument that made a return in the middle of the 19th Century.

Perhaps I have not seen enough such pieces, but 1829 looks early for this style of monument,

and I would think that it was put up some time after the last named figure commemorated on the monument, who died in 1839.

- Thomas Watkins Yardley, d.1840, simple tomb-chest end, with little feet, upper shelf, rather prominent,

top like a pediment and plain acroteria. On a black backing.

Lees and Brown monuments, casket plaques of the 1840s.

Lees and Brown monuments, casket plaques of the 1840s.

- Frederick Lees, d.1844, in the form of a casket end, with outward angled sides,

a chunky top with a low relief sculpture of an urn and some light scrolling on it, and little rounded feet.

On a black shaped backing. Such panels in the shape of a casket were a frequent alternative to the tomb-chest end

shape which was the most common type of the period.

- Benjamin Brown, d.1844, in a variation of the casket theme, this time crisply classical in form,

with acroteria at the corners on top, carved lion’s feet underneath, and resting on a thin shelf with two chunky supports and a curvy apron in between.

The mason obviously felt that the feet were too small to convincingly bear the weight of the casket,

so has infilled most of the space between shelf and base of casket with a further angled piece of marble.

All on a black shaped backing.

- Harriott Whitehouse, d.1852, husband Jesse Whitehouse, d.1860, and daughter Betsey Jane Whitehouse, d.1862.

Styled as a tomb chest end, with upper shelf bearing a lid on which is a low relief sunburst with a small cartouche

bearing the letters ‘IHS’ for ‘Jesus’. At the base, two feet carved as scallop shells, most elegant.

The whole on a black backing and signed by Bennet and Son of Birmingham, an obscure firm, to me at least.

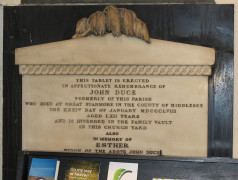

John Duce, d.1858, with allegorical wilted branch.

John Duce, d.1858, with allegorical wilted branch.

- John Duce, d.1858, and wife Esther, with an upper string course of a repeating Roman S-shaped pattern,

and on the top, the by-now-familiar wilting branch, with many leaves.

- Phillip Williams, d.1864, of Wednesbury Oak Tipton, ‘prominently connected with the Coal and Iron Trade’

and High Sheriff, Deputy Lieutenant and Magistrate for Worcester. An interesting tablet, as a horizontally elongated circle

rather than a true oval, with trefoils around, each with a pendant in the form of a stylised leaf, giving a varied outline.

Double spandrels between the trefoils are carved with low relief leafy decoration, and larger corner spandrels

have larger scale leaves. The whole is set in a Serpentinite frame. The text of the memorial is in black letter with the capitals

picked out in red, common for this period.

- Mary Ann Richards, d.1885, with a list of her various benefactions to Wednesbury,

including giving her valuable collection of pictures and £500 to clean them, and £2000 towards the erection of an art gallery,

and £1000 for a curator for it, thoroughly to be commended. There is a Museum and Art Gallery in Wednesbury,

but I do not know if it still includes the Richards collection. The monument consists of a white panel with a thin border

of alabaster, and carved corner pieces showing leaves, on a black backing.

After 1900:

- Plaque by Ellen Jones, 1903, commemorating her parents, Edward and Mary Nayler,

her siblings, and her husband the Revd. John Jones, and that she erected the transept and furnished it with

oak panelling and seating, with an Arts and Crafts alabaster border with leaves and grapes, and a frieze of them above,

flanking a shield bearing the letters ‘ihs’ for ‘Jesus’, and an apron with broader leaves.

- Thomas Pritchard, d.1910, and sister Jane McDougall, d.1911,

and noting that the church bells were recast at the cost of their various children, who on the Pritchard side

included the Mayor of Birmingham and a Vicar of the Church. White panel with characteristic 1900s frame,

in coloured alabaster, with various little leaves and at the top, a cartouche enclosing not a coat of arms,

but a low relief carving of two church bells ringing. Little flowers are carved around the sides of the frame.

View of interior of St Bartholomew's, Wednesbury.

View of interior of St Bartholomew's, Wednesbury.

A few words on the Church itself. It is of medieval origin, the earliest parts of the fabric dating from perhaps

the 13th Century, including a couple of windows and the lower parts of some of the walls,

and a rebuilding of the 15th or early 16th Century. However, ruthless modernisation in the early and later 19th Century,

and again in the 20th Century, mean that the Church does not have a medieval feel inside,

but more of a bright late Victorian church. So it is mainly the older monuments which declare the building’s history.

The architect Basil Champneys was asked to make suggestions on refurbishment and enlargement in the 1880s,

and his proposals formed the basis of later work: this included the wholesale movement, stone by stone,

of the multi-sided apse, which dated from the 15th/16th Century, some distance eastwards to allow enlargement

of the main accommodation. That work exposed the tombs of Richard Jennyns (d.1521) and John Comberford (d.1559),

which may have been reinterred. The apse has been well decorated in a unified scheme involving stone panelling,

painting and gilding, bright stained glass windows, and an alabaster altarpiece with sculpture.

This latter includes a triptych arrangement with a central scene of Christ breaking bread with two saints,

really rather High Church in feel, and two groups of three standing saints to the sides – St Bartholomew

is the one with the flaying knife, indicating the manner of his martyrdom.

Most interestingly, the front of the table below has painted and mosaic decoration, comprising five standing figures:

in the centre, Christ flanked by two angels, with St Peter on one side panel, and another on the other side with

a dragon in a cup, which indicates poison, thus St John the Evangelist (who also features among the small statues).

The figures are painted on stone, in pieces as if stained glass, with mother of pearl haloes,

and the blue sky behind and the outer edgings of the figures in mosaic. The ground for the central panel

is delicately painted in a Burne-Jones style, rather otherworldly and most effective.

Excellent work of the 1880s or a bit later.

Altar of St Bartholomew's Church, and details.

Altar of St Bartholomew's Church, and details.

Also worthy of mention are the Jacobite pulpit, the ancient wooden lectern and a 16th or 17th Century chest,

and the later woodwork and alabaster stone tracery. Two large, grey panels record the various bequests and gifts to the Church,

‘copied from decayed wood tablets dated about 1808’, and other panels record the restorations and additions in the early

19th Century and later. But other details abound, including a charming little St George and the Dragon, pictured here, 1880s

at a guess. (If you like St George statues, there is a whole page of them here.) And there

is good stained glass (see example at top of page), mostly by C. E. Kempe, including a pagan 'Woden window'.

The Church is not usually open outside of services, and as with most churches, it is important to get in touch

before making a special visit. With thanks to the Vicar, Tim Vasby-Burnie, for a tour and information,

and permission to include photos from inside the Church; the Church uses the website of the Lichfield diocese, at

http://www.lichfield.anglican.org/

Top of page

St Leonard's Church, Bilston // St Peter's Collegiate Church, Wolverhampton // St John in the Square, Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton sculpture // Birmingham sculpture // Sculpture in some towns in England // Introduction to church monuments

William Hollins // Peter Hollins // Sculpture pages

Home

Visits to this page from 10 May 2014: 16,007

Monument to Thomas and Elianor Parkes (he d.1602).

Monument to Thomas and Elianor Parkes (he d.1602).

Memorials to Jesson and Hodgkins, 1770s.

Memorials to Jesson and Hodgkins, 1770s.

Bust of Isaac Clarkson, by Peter Hollins.

Bust of Isaac Clarkson, by Peter Hollins.

Thursfield and Williams monuments, 1820s, the humble and less humble ends of Gothic.

Thursfield and Williams monuments, 1820s, the humble and less humble ends of Gothic.

View of interior of St Bartholomew's, Wednesbury.

View of interior of St Bartholomew's, Wednesbury.

Altar of St Bartholomew's Church, and details.

Altar of St Bartholomew's Church, and details.