It should be admitted at the outset that the camel is not the most conspicuous feature of Victorian and Edwardian sculpture. However, there are a few free standing camel statues to be found, and a larger number of camel sculptures in high relief. We start with the largest and most important, which is of course the camel to be found in the Africa group for the Albert Memorial, by the sculptor William Theed the Younger. The camel is seated, with an Egyptian princess seated on its back in that curious fashion that people sit on camels. The way the camel sits is in that equally peculiar double-jointed way in which camels sit, and demonstrates well the long, bowed neck, and lugubrious face of the beast. This camel is decorated with teardrops hanging from its harness, and although the robes of the girl make it difficult to pick out what lies underneath, it seems the camel bears not a saddle, but is covered with a blanket across the shoulders, back and hump. It is interesting to see a camel as a symbol of Africa, because this is an allegory of North Africa, the Africa of the Ancient Egyptians and the modern Arabs, rather than the more southerly Africa. We see this too in the balance of the surrounding figures, which include an apparently Egyptian boy, his hand on a small Sphinx, to accompany the Egyptian princess, a turbaned Bedouin tribesman of biblical countenance, a European female, rather civilised, with a scroll, perhaps an explorerís map, and a single African warrior, savage and naked. From the perspective of the camel, the most interesting figure is the Arabic one, who has beside him a large, wrapped parcel and three pieces of ivory, indicative of trade, much associated with camels.

Two views of the Albert Memorial camel group (Africa), by William Theed.

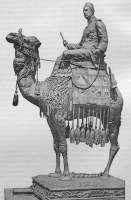

A free-standing statue of a camel which is not seated really has to be in metal, bronze in the Victorian and Edwardian era, and Onslow Ford made a full size statue of General Gordon mounted on a camel for Chatham, and later Khartoum, from whence it was returned in post Colonial times. Much emphasis here on the pose, with the upturned head of the camel well capturing the animalís typically independent, sneering look, and also on its exotic nature, emphasised by the gaudy trappings and long tassels from the saddlecloth. In London there is one small bronze camel with mounted rider, which is the Imperial Camel Corps memorial on the Victoria Embankment, by the sculptor Cecil Brown, put up in 1921. Cecil Brown was himself at one time in the Camel Corps, and his other work includes various equestrian subjects, again reflecting his wartime experiences. There are panels at the base of the memorial, and one of these includes a sitting camel, also shown here.

General Gordon by Onslow Ford, and the Imperial Camel Corps Memorial by Cecil Brown.

Stone camels in standing position are of course possible if there is a backing, as in a pediment, with the camel either as an attached sculpture (alto relievo), or as a carving in relief.

William Theed's camel panel in Eastcheap, City of London.

William Theed's camel panel in Eastcheap, City of London.

Above, then, we have an example of a sculpture of the trading camel, in a curved relief panel in Eastcheap in the City of London, showing three camels bearing heavy baggage, led by an Arabic figure with a staff. Again we see the camels have blankets over their backs, and they are linked by light ropes or leads from the harnesses, which bear decorative fringes. The centremost camel has woolly legs and something of a mane, indicating he is the dominant male; the others are presumably female or more youthful. They are led by a striding Arabic trader carrying a staff. Oddly enough, or perhaps not, William Theed the Younger, whom we met in the Albert Memorial camel, was again the sculptor.

Camel sculpture indicating trade, Liberty's camel and the Manchester Free Trade Hall camel.

Camel sculpture indicating trade, Liberty's camel and the Manchester Free Trade Hall camel.

Much more massive is the camel sculpture on the long frontage of Libertyís to Regent Street, again indicating trade, and one of the exotic sources of Libertyís wares. The camel is seated, with two Arabic traders, and one naked worker who is in a pushing position, perhaps urging the camel to get up. Free Trade is again the theme of the camel above right, with an allegorical girl seated upon it, holding a cornucopia (symbol of plenty) and an overflowing jewel box, while beside her is an ornamented pot and other accoutrements from the region. This excellent sculpture, by J.E. Thomas, is on the frontage of the Manchester Free Trade Hall - see this page.

More trade examples. Above left, a heavily-furred camel, if that is the right term, with a European attendant, forming one half of a symmetrical composition above a round arch in the spandrel position. The camelís head and neck nicely fill out the available space into the square corner of the spandrel. The central picture above shows another camel in a spandrel, this one very much in the background, as a low relief sculpture, surrounded by palm leaves and backing a semi-nude girl, barbarically and enchantingly dressed with long skirts, strings of jewels around neck and breasts, and holding a fan made of feathers. The camelís familiar haughtiness is evident, and the tassels, here on the strap leading from its jaw, but the chest is unusually curved and large. Above right is another group of girl and camel, with camel in the background, but here we have a very three dimensional sculpture, supported at back and head by being within a curved pediment. The camel is curly browed and has the tassels on its bridle, and the girl, while dressed in Classical costume, has an African headpiece with cloth binding her abundant hair, and some ornament at the front.

Heraldic camels as supporters.

The camel may also be found in heraldry, and here are a couple of examples. Above left, two rearing camels as supporters of a central shield, their pose being more like that of a lion than convincingly camel-like; the knee joints are wrong. They are of the one-humped variety, unlike most of those above where we can see the back, so properly dromedaries, and not particularly the customary baggage camel, but rather the racing kind. Next, two pairs of camels, versions of the same coat of arms, from a building in Threadneedle Street by the Bank of England, the first rather gaunt but with distinct humps at least, the second pair almost humpless, and recognisable as camels mainly from the S-shaped curve of their necks.

Camel bench on the Victoria Embankment.

Camel bench on the Victoria Embankment.

Perhaps the camel sculpture that Londoners and visitors to London encounter most frequently in day to day life, though, are the camel benches along the Embankment next to the Thames. They are not confined to one area, but there seem to be more near to Temple than elsewhere. They are of necessity somewhat simplified in rendering, but manage to distil down much of the essence of camelhood: the grand curve to the neck, the knobbled and awkward knee joints, the heaped up burdens on the back. Only in the expression are they somewhat lacking the spark of camel sapience.

Finally, I wanted to include an example of a Biblical frieze incorporating a camel, and here is such a frieze by George Tinworth, the sculptor in terra cotta, called Joseph is sold to the Midianites. There are three camels dimly seen in the rear of the main scene, low relief compared to the attached statues in front of them, and one seated camel emerging into the foreground, and along with the palm trees, the camels give the necessary exotic ambience to what could otherwise be a difficult to place scene.

Visits to this page from 10 Sept 2014: 13,335

Sphinx sculpture // Animal sculpture // Allegorical sculpture