St Marks Kennington, Oval - Monuments

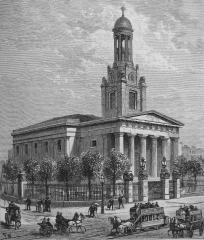

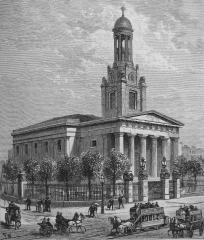

St Marks Kennington, by the Oval Cricket Ground, is a significant church

built as one of four ‘Waterloo Churches’ built by the Commissioners for building

new churches to celebrate the victory over Napoleon. It was put up from 1822-24,

the architect being the obscure David R. Roper, who has a few surviving buildings

in South London. It is in Classical style, with a six-column portico in front

of a blocky nave, and a tower behind the portico which is square sided in two stages,

with clocks at the higher stage, and then a cupola raised on tall pillars,

rising to a little dome with a cross on top. The site is excellent, with views

of the Church all round, and from across the busy main road.

St Mark's Kennington, exterior.

St Mark's Kennington, exterior.

The Church suffered extensive bomb damage in WWII, being left as a roofless shell,

but has been restored extremely sensitively. There are low aisles, a nave as broad as it is tall,

Ionic pillars at the chancel end, and a dome of coloured glass evoking a sunlit sky.

Along the upper walls of the nave, where a clerestory would otherwise be, are abstract panels,

and small panels showing pairs of winged lions, symbol of Saint Mark and of Venice.

The interior is painted in a very light pastel blue with white trimmings, most elegant and light.

A tribute to the architect and the interior designer.

St Mark's Kennington, exterior.

St Mark's Kennington, exterior.

There are just over 30 monuments, nearly all from the 1820s when the Church was erected through to the 1840s.

They are rather simple in design, and some just the plain, central inscribed panels,

presumably after War damage – one damaged piece with a figure collapsed and crumbled away as recently as 2012.

Several have some projection on the wall, white painted and perhaps of plaster or wood,

to indicate the shape of the surround to the original monument (at the period these monuments were made,

the backing would almost always have been black marble or stone. These monuments are therefore more of social

and historical than artistic interest. Nevertheless, we have several of the main types of early 19th Century panel,

and a bit of carving, including two minor works by significant sculptor-masons, as well as a few modern brasses.

There is also excellent mosaic work on the Reredos, and a more recent naďve mosaic roundel from after 1900.

We consider first the more interesting monuments, from a sculptural point of view, and then the rest:

Monuments to Elizabeth White and James White: work of Charles H. Smith and William Croggan

These are the two signed monuments, to members of the same family:

- Elizabeth Earles White, d.1828, and husband William White, tall panel with receding border,

and a segmented (curved) pediment above, cut with acroteria. Within this is a carved wreath with curly ribbon.

At the base, thick shelf and two blocky feet. By Croggon of New Road, Lambeth. William Croggan or Croggon was

the cousin and one-time partner of Eleanor Coade, Lambeth manufacturer of the widely-used artificial Coade Stone.

Elizabeth White, d.1828, by William Croggan, and James White, d.1833, by Charles Harriott Smith.

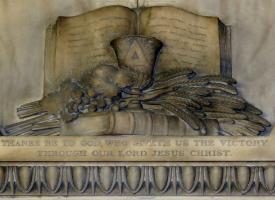

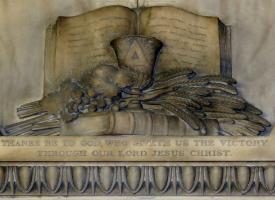

- James White, d.1833, his wife Ann White, d.1829, their son,

Robert Milward White, d.1818, ‘a Lieutenant in the East India Company’s Military Service,

who died at the fort of Amednugger’, another son, Percival White, d.1850, and his wife

Amelia Rebecca White, d.1837. Panel with upper shelf with repeating pattern on what might be described

as the architrave, with acroteria at the sides, and in place of a pediment, a sculptural pile of book,

chalice resting on another book, grapes, and a sheaf of corn, emblematic of Religion, learning, fruitfulness.

At the base, a deep shelf with upon it a finely carved rendering of a stem of poppies, wilted, indicative

of sleep becoming death. Beneath are side brackets with anemone carving, and a central apron with small shield of arms,

now blank. The work is signed by C.H. Smith of 29 Clipstone Street, Fitzroy Square.

Charles Harriott Smith was a fairly successful member of a family of monumental sculptors, active through till

about 1850; another London monument by him is noted on the page on St John’s Wood Chapel.

Monuments retaining carving or border:

These are the monuments which either remain complete, or have at least something beyond the central panel

with the memorial inscription. That to William Cox, rather later than most of the monuments in the Church,

is the best of the bunch in terms of carving. We take them in date order:

- Joseph Lamb Webb, d.1823 or 25, his brother Henry Webb, ‘who on the same day

and in the same hour died at Antigua in the West Indies’, and others of the Webb family through to 1873.

With upper shelf, and resting upon it without any gap, a small pediment and acroteria,

lightly carved with leafy designs. At the base, two feet with dog-teeth, and between them,

a note that the monument had been moved from St Michael’s Crooked Lane.

Joseph Webb, d.1823/5, and decayed obelisk to William & Sarah Webb, undated.

Joseph Webb, d.1823/5, and decayed obelisk to William & Sarah Webb, undated.

- William and Sarah Webb, undated, also moved from St Michael’s Crooked Lane,

‘when the Church of that parish was taken down for the approaches to the new London Bridge’.

Rather a sad monument: the inscription is on a semicircle, below a shelf supported on two carved corbels,

on which rests the outer border in black marble of an obelisk monument, with the interior space entirely crumbled away;

the remains of some carved flower is at the top. I asked the gentleman in charge of the Church what had been there,

perhaps a carving of a girl with a pot, and he said that there had been something like that,

but having seen it hundreds of times over several decades, he had never looked at it properly,

and it had simply collapsed off the monument and crumbled away in about 2012 or 13. A shame.

- Joseph Harrison, d.1825, erected by his brother William Harrison.

Panel with upper shelf and upon it, squared off pediment bearing a simple carving of crossed palm leaves. Humble.

Small panels, horizontal composition: Harrison, Horneman, Thorpe, 1820s.

- Henry Frederick Horneman, d.1825, His Danish Majesty’s Consul General in London.

Plain panel, with under it, a shield of arms. The plaster backing is raised to indicate the shape

of the original backing panel, with the shield occupying a semicircular apron.

- Francis Elizabeth Maria Smith, d.1828, and her mother Fanny Wootton, d.1839,

and her son Thomas Smith, d.1818. Tall panel with blocky upper shelf, on which is a small carved pot,

partially draped, in central position, with acroteria (ears) to the sides. The monument, like others in the Church,

is mounted on a painted white-painted backing, shaped to have a pediment at the top.

At the base of the inscribed panel is another blocky shelf, under which are two supporting brackets,

carved with Acanthus leaves (picture below left).

- Mary Thorpe, d.1828, cut with feet, and with upper shelf beneath a blank pediment (see picture above right) –

a not uncommon modest type of Classical panel.

- Laura Frances Hill, d.1830, stone panel with border and small, blank pediment resting directly on top.

- Catherine Fentiman, d.1832(?), panel with upper and lower shelf,

above which is a two-step pediment with a blocky crucifix in front of it: no carving, just cutting.

At the base, apron and two angular supports.

Vertical compositions: Smith and Hood monuments.

Vertical compositions: Smith and Hood monuments.

- Mary Hood, d.1832, and William Hood, d.1840, a young child.

A tall panel similar to that of Francis Smith noted above, with the inscription only occupying the upper portion,

the lower portion never having been used. Upper and lower shelf with mouldings,

and at the top, cut to the shape of a blocky pediment with a roundel in the centre (picture above right).

- Martha Poole, d.1836, with a brief eulogy. Panel with inscribed line border, curved base,

upper shelf and rimless pediment with the inscription ‘Thy will be done’.

The backing in white plaster includes little feet.

- George William Towton, d.1837, of Jamaica, who died at sea. In the style of a casket end,

thus with outward slanting sides, and with feet resting on a shelf, itself supported on two moulded brackets.

At the top, a central Aladdin’s lamp-style pot or funereal urn is carved in high relief, with at the sides,

two rounded acroteria. The white backing here is carved with a pediment shape on top,

and underneath is a low relief carving of crossed, drooping branches,

and a central curved shape that might be a snake, certainly scaly, though with the rear end and tail is missing.

That would be indicative of Wisdom in this context, and the drooping boughs of course indicate death, or life severed.

See picture below left.

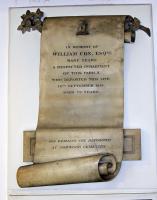

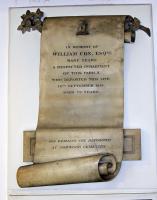

- William Cox, d.1851, carved as a hanging scroll. This was a moderately widespread alternative

to the normal blocky panel monument from the 1800s onward. The scroll is unrolling vertically,

and is rather more ornate than the usual for this type of monument. Thus the top is hanging over a leafy branch,

finely carved, and the bottom hangs in front of a letter-box like horizontal panel,

so being pushed forward to create a separate section of the scroll with the inscription that he was buried at

Norwood Cemetery. Some nice attention to detail, as in the rings on the cut end of the branch (picture below, centre, click to enlarge),

and a low relief of a goat’s head at the top.

Towton and Cox monuments, the latter carved as a hanging scroll.

The rest of the monuments:

For completeness, though of less interest to this website with its artistic preoccupations,

the rest of the monuments, simple plaques, mostly rectangular, separated from any sculptural border or ornament

some of them may have had before the bombs of WW2, are listed below:

Modern brasses:

- William Sopper, d.1897. and his wife Anne Sopper, also d.1897.

With black lettering and red initials, as is characteristic of the modern brass.

The shape is as an arched window, more segmental and broad than Gothic, and there is a double line inscribed border,

with circles at the corners, each containing a small geometrical device, slightly arts and craftsy.

- Vincent William Lynn, d.1901, Treasurer of the Bolton Street School.

Long, thin panel with black lettering, in capitals, with the principal initials picked out in red.

The border contains simple repeating designs of leafy vines, much stylised, and there are Gothic crosses at the corners.

By J. Wippell & Co. Ltd, of Exeter and London.

- Frederick Gibson Lynn, Churchwarden 1898-1905, the text is in black, with the initial letters

picked out in red as we have seen before. The border consists of pairs of stylised leaves,

with the same Gothic crosses at the corners as the earlier monument.

- Revd. Arthur Gerald Bowman, d.1904, Vicar of the Church, with the normal black and red text.

There is an inscribed line border, with crosses at the corners, and a raised half circle at the top,

enclosing crucifix, crown, and leaf designs. There is a white outer frame in plaster. By J. Wippell & Co. again.

Typical modern brass, to Revd. Arthur Bowman, d.1904.

Typical modern brass, to Revd. Arthur Bowman, d.1904.

Also in the Church:

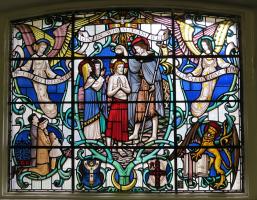

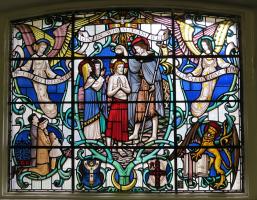

W.C.T. Shapland's stained glass design, 1952.

W.C.T. Shapland's stained glass design, 1952.

Outside the Church:

The gravestones from around the Church have been cleared and placed against the railings

at the edge of the small open space. A few worn, slight sculptural details can still be seen.

Across the main road is Kennington Park, wherein are a few memorials of interest:

- Slade Drinking Fountain, put up in 1861 by Felix Slade, founder of the famous art school.

There was once a vase on top with relief sculpture, but that is gone, and what is left is the heavy bowl,

of red granite, with mouldings and slight repeating ornament on the stem.

Around the sides of the bowl are inset white roundels with weathered low relief carving, nothing exciting.

Slade fountain, and remains of Doulton fountain, Kennington Park.

- The remains of the Doulton Drinking Fountain, a pink terra cotta column on a broad base,

with the firm’s typical decorative treatment, including fine olive branches modelled in relief.

Once there was sculpture: a relief, and a statue of a man carrying a cross, with a woman and child –

a plaque by the pillar shows a photo of this – but War damage and vandalism saw the end of that.

George Tinworth of Doulton’s was the sculptor.

- The Queen’s Royal Regiment Monument, an obelisk within a railed enclosure,

bearing upon it a carved wreath with a Lamb of God within it.

- There is a lodge, once a model for working class homes, commissioned by Prince Albert

and shown at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

Queen's Royal Regiment Monument.

Finally, two artistic connections. Firstly, the artist David Cox lived close by,

in Vassall Road; a blue plaque marks his residence there. Secondly, Kennington Oval

was the location of J. Whitehead and Son’s marble works, known as the Imperial Works.

As well as marble work for commercial buildings, Joseph Whitehead

made the Titanic Memorial for Southampton, and the World War I memorial for

Worthing, with a bronze figure.

With thanks to the Church authorities for permission to use photos from inside St Mark's Kennington;

their website is at http://stmarkskennington.org/about/history/.

A short walk north and west past the Oval Cricket ground leads to Vauxhall Bridge with its imposing statues.

Or north-eastwards along Kennington Park Road, then branching off north west along Kennington Lane leads to the idiosyncratic

little building of Durning Library, 167 Kennington Lane.

And thence to Black Prince Road and the Doulton building.

Top of page

Monuments in some London Churches // Churches in the City of London // Introduction to church monuments

Angel statues // Cherub sculpture //

London sculpture // Sculptors

Home

Visits to this page from 17 Jan 2016: 1,021 since 15 March 2025

St Mark's Kennington, exterior.

St Mark's Kennington, exterior.

St Mark's Kennington, exterior.

St Mark's Kennington, exterior.

Joseph Webb, d.1823/5, and decayed obelisk to William & Sarah Webb, undated.

Joseph Webb, d.1823/5, and decayed obelisk to William & Sarah Webb, undated.

Typical modern brass, to Revd. Arthur Bowman, d.1904.

Typical modern brass, to Revd. Arthur Bowman, d.1904.

W.C.T. Shapland's stained glass design, 1952.

W.C.T. Shapland's stained glass design, 1952.