Running east and south from the Albert Embankment of the River Thames in London is Black Prince Road, and a few paces along this street is a treat – the remaining part of the former factory and showroom of Doulton’s of Lambeth, dating from 1876-78. Once there was a vast site with three or four factory buildings, but just this one survives. The best view is on the approach, when we see the full impact of the decorated corner, which was the showroom. It is not so large – just two bays either side of the corner door, after which the building is much plainer, but what a corner. The main feature is the corner turret, rising from above the door and supported on an ornamented corbel, in two spiky, polychromatic storeys to a hexagonal steeple. Under this, the corner doorway has a tympanum with a nice sculptural scene in terra cotta – we will come back to this in a moment – and the windows on the ground floor to the sides are slightly pointed. The next storey up has rectangular windows, with square pilasters to the sides, and these are but the lower part of the 2nd storey windows, tall properly Victorian Gothic things, so that upper and lower windows together look like one tall, slender whole. The third storey has smaller windows, three on each side rather than two, Italianate style Gothic, if you will, and then is the protruding cornice and the Mansard roof. Every part of this corner is highly decorated in terra cotta, in pale pink, three shades of red, and darker blue-black tile.

Doulton factory building, Black Prince Road, Lambeth.

There is much ornate foliage, in repeating and varying patterns, patterned tiles of multitudinous forms, and higher up, the capitals of the pillars are delicately moulded, with curled leaves and small birds, and the 1st floor pilasters have further floral and avian decoration. Here and there are small creatures, all sculpted in terra cotta, including whimsical little owls (more owl sculpture on this page) and fierce gargoyles. Richest of all in the decorative scheme is the supporting block or corbel to the corner turret, with concentric circles of repeating designs in a display of virtuoso manufactured terra cotta.

Doulton building: terra cotta details.

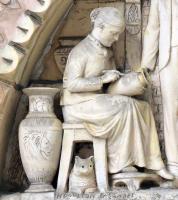

And the tympanum – the Gothic arch above the squared off door. The sculptural scene, in a pale terra cotta, shows a group of buyers and sellers of Doulton pots. There are six figures in all in the busy scene, attached rather than high relief, excepting for one relief figure in the background. On the far left, a girl is seated, either examining or perhaps inscribing or painting a pot which she has on her lap and in one hand. A cat is seated under her stool, oblivious of the lion head inscribed on the pot next to her. The second figure is a standing, bearded gentleman in hat, suit and tie. Then a hatless man, the only one, holding a large pot across his chest, and then the figure to the rear, carrying balanced on his head a rack with delicate pots. Next, a seated figure, hand gesturing towards the pot held by his companion, but turned to look round and up towards the final figure, another workman, I would think, hand on the largest pot of all in the composition, which stands on a small plinth, signed with the monogram of the sculptor, George Tinworth. The composition is charming and well-balanced, the quality of the sculpture tending somewhat to the pictorial, extremely characteristic of the self-taught Tinworth. He made many plaques and tympana with figures, typically religious in nature rather than secular as here. For a little more on Henry Doulton, see this page.

George Tinworth tympanum on the doorway of the Doulton building.

Beyond the corner, the long side of the Doulton Factory to Black Prince Road is much plainer, though still with fine effect from the bright red terra cotta with slightly black banding, many windows, with little Gothic attached pillars to the sides on the upper floors, and a generally pleasing aspect. Passing under the railway bridge, and looking back, we can see the restless skyline of the building and the fine Mansard roof, rising to a little viewing point with delicate, leafy iron railing.

Doulton factory from beyond bridge, decorated corbel, and steeple.

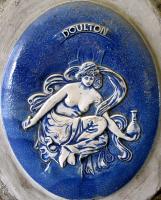

Under the bridge itself, the walls of the tunnel are enlivened with a series of little ovals, some glazed pottery, some mosaic, illustrating respectively Doultonware and the Black Prince – the road was named after him because, as one plaque informs us, owned nearby Kennington Manor. Modern pieces, light rather than serious, the artists are listed as Duncan Hooson, Ali Samiei, Janet James, Sue Edkins, Howard Grange, Zahir Shaikh, Ruchita Shaikh, David Tootill, Mario D’Oliveira, Elisa Camfield, Joanna Rice, Josie Harris, Jigna Patel, Jacqueline Howell and Jasbir Lally.

Ceramics and mosaics in the Black Prince Road railway tunnel.

A few yards further, on the other side of the road, are two taverns, the second of which, on the corner of Tyers Street, has minor architectural sculpture. There is a high relief figure piece above the door, showing two farm labourers standing with vaguely seen trees behind them; one rests on a space, the other carries a long scythe – the pub is today called ‘the jolly gardeners’. The windows on that floor have further decoration in the shallow arches above the windows – decorative scrolling and cornucopias, with central faces. All rather light and jolly, characteristic of the type.

Tavern on corner of Tyers Street, and sculptural decoration.

A little further on, on the right hand side, is the former Beaufoy Institute, a nice Edwardian building of red brick and terra cotta, with minor decorative features, especially around the central doorway and the bay on either side: festoons of flowers between cartouches above the ground floor, decorative moulded tiles with leafy designs, beautiful Arts and Crafts lettering, and further cartouches on the gables, including the date of the building, 1907. The architect, noted on a foundation stone, was F. A. Powell, and the text notes that Mildred Scott Beaufoy, wife of the then-Chair of Governors, Mark Hanbury Beaufoy, laid that stone. The most interesting element from the point of view of these pages is the large plaque on the front, above this stone, with a calm sculptural scene of a teacher, dressed in Classical robes, standing and pointing to some lesson in her book, held by a small child. A boy, a little older, is seated to the right, hand on heart, other holding a closed book with thumb inserted to mark the page. They wear the simplest of clothes – a shift for the younger child, a ragged shirt and trousers for the older, and both are barefoot. Behind is a flaming torch. A good piece of illustrative sculpture by the sculptor Samuel Nixon. The date of the sculpture is clearly far older than the building it adorns, and it turns out that it was moved from the original building of the Beaufoy Institute, built in 1850-51. It had been Henry Beaufoy, distiller and vinegar manufacturer of Lambeth, who had build a Ragged school just off Black Prince Road in Newport Road, later becoming the technical school on this site. The heraldic symbol of his family, shown on the foundation stone, was a symmetrical tree in full leaf, and this same design can be seen on the monument to Henry Beaufoy in Ealing Parish Church. A supporter and trustee of the School was Henry Doulton, and apparently the interior has much decorative tilework of a variety called ‘Cockrill-Doulton Patent Tiles’.

Beaufoy Institute, 1907, and 1851 sculpture by Samuel Nixon.

It is worth a look down Newburn Street, to see the excellent almshouses called Woodstock Court. The architects were Adshead and Ramsey, and this charming grouping with its central courtyard and human scale dates from 1914.

Right at the south end of Black Prince Road, where it meets Kennington Road, strictly on Sancroft Street, is St Anselm Church, a small basilica of stock brick like a very early Christian church. It was designed by S.D.Adshead and S.C.Ramsey, intended as a rather grander church than actually built, with a dome. But while building started in 1914, it was stopped by World War I, and the more modestly designed Church was only completed in 1933. The remarkable feature, above the door, is the tympanum (semicircular shape), which contains a contemporary statue of St Anselm, seated between lion and lamb, an oddly stylised group, naďve in manner and with a clear Orientalising tendancy. The sculptor was a modernist, Alfred Gerrard, and the work dates from when the Church was erected. Gerrard was more significant as a teacher than a sculptor – Paolozzi studied under him for a period – and his public works seem to be rather limited. The most familiar statue by him is one of the Winds high up on the London Underground HQ above St James’s Park Tube Station. There is further work by Gerrard inside St Anselm’s Church: roundels with a lamb and dove, and capitals to the interior pillars with leaves and simple repeating patterns of birds and animals. The Christ and two angels carved in high relief on the font are by a different sculptor, Derrick Frith. Likely by a different hand again are the exterior pillars and decoration round the tympanum edge, which are more traditional designs.

St Anselm, Kennington, and Alfred Gerrard sculpture.

We may note that on the opposite side of Kennington Road and just round the corner is an attractive late Victorian building, Durning Library, described on this page.

This page was originally part of a 'sculpture of the month' series, for June 2016. Although the older pages in that series have been absorbed within the site, if you would wish to follow the original monthly series, then jump to the next month (July 2016) or the previous month (May 2016). To continue, go to the bottom of each page where a paragraph like this one allows you to continue to follow the monthly links.

West and South to Vauxhall Bridge // South to St Mark's Church, Kennington // Albert Embankment Gardens.)

Borough to Bermondsey: churches and sculpture // London sculpture // Sculptors

Visits to this page from 1 June 2016: 10,815