The centre of Portsmouth in the civic sense is not the dockyard but Guildhall Square, where stands the enormous 1880s Town Hall, later called the Guildhall, faced by the statue of Queen Victoria, and with the city’s main war memorial to one side. The Guildhall has significant sculpture, as does the War Memorial, and the Queen Victoria is statue is by Alfred Drury, one of the most important sculptors of the period.

Portsmouth Town Hall, renamed as the Guildhall when Portsmouth gained City status in the 1920s, is an extremely large, grand Classical building, with a Greek portico and free-standing Corinthian pillars along its frontage, and behind, a towering clock tower of extreme solidity and mass. William Hill of Leeds was the architect, and the building was put up from 1886-1890; he himself was dead by then, and the completion of the building included some changes from his design, which was based on his previous Town Hall for Bolton, rather smaller, but still on a massive scale. Further changes to the Portsmouth building came after damage in World War II, with the loss of several of the turrets and cupolas that previously decorated the building; the interior was largely gutted. Consolidation of what was left and rebuilding has left today’s building with two cupolas seen from the front, one behind each end of the pediment, and a somewhat shortened central tower, and loss of some of the non-figural decorative features. The entrance is reached up a series of broad steps (as in Bolton), and this, with the wide space of Guildhall Square in front of it, enhances the apparent scale of the building. The Town Hall, or Guildhall, remains as a splendid example of civic pride expressed through architecture.

The interest of these pages is, of course, the sculpture, and we look here at three elements: the pediment of figure sculpture; the three free-standing groups on top of the pediment; and the pair of stone lions to either side of the portico.

Pediment of Portsmouth Guildhall, by H.T. Margetson.

Pediment of Portsmouth Guildhall, by H.T. Margetson.

The pediment is the principal work of the sculptor H. T. Margetson. It contains a dozen figures in total, together with several large animals, and a variety of accoutrements. The subject seems to be Britannia receiving the trades of the world, represented by the Continents. We start at the left hand side:

Statue of Seaborne trade, left end of pediment.

Statue of Seaborne trade, left end of pediment.

A reclining nude male figure holding a chart, with a large cogwheel and a slab inscribed with a triangle by his foot; perhaps indicative of Industry. (A variety of allegorical figures of Industry are on this page.)

Allegorical statues of Egypt (Africa), South America and North America.

Allegorical statues of Egypt (Africa), South America and North America.

Next, a group of three figures and two animals; a reclining girl with camel behind her, then a standing male figure, then a larger female, holding a bison. The reclining girl together with the camel, of which we see in profile the head, neck and part of the back, would seem to be a personification of Egypt, doing service here for the Continent of Africa as a whole. She has a headdress consisting of a bird diadem on her forehead with outstretched wings, rather like that on the Albert Memorial group (see picture on this page), and long cloths which act as sidepieces, lying over her shoulders and breasts. One hand rests on a small chest, presumably of tradeable goods, the other holds a piece of fabric and perhaps some other item too worn to determine.

Standing next to the Egyptian princess is a statue of a man dressed in a kilt of feathers, a broad-shouldered fellow, muscular in arm and leg and neck, and holding a spiked club. He may represent South America, based on the feathery kilt, and that the standing female next to him would seem to be North America by virtue of her hold upon the bison, an animal of some heft, with short horns and much curly hair on head, neck and chest. The woman is solidly built, wearing classical garb, rather light to show the lines of the body, and with plaited hair.

Mercury reclining, with one of Britannia's attendants (right).

Mercury reclining, with one of Britannia's attendants (right).

Next, the central group, of five figures centred on Britannia. To the left, a reclining figure of Mercury, messenger of the Gods. He is nude, holds a short bronze winged staff, and wears a helmet with decayed wings. By convention, he is youthful and muscular, but athletic in build rather than with the physique of a wrestler. Next to him on the steps is seated a small lion, staring straight forward, all woolly mane and big front paws, and in an 18th Century emblematic style rather than anything naturalistic.

Behind, stands a female figure, dressed in Classical drapery with loose sleeves. Her hands are empty, but previously held some staff – I have only seen a very blurry picture of this and do not know what it signified, though it would be nice to think she could represent the dead weight of bureaucracy. The remarkable feature of this figure though, is the thickness of the neck, hard to imagine even on the strongest Amazon; there is a hardness to the face, too, which is made little more feminine by the long curls of hair.

Central statues on pediment: Britannia and attendants.

Central statues on pediment: Britannia and attendants.

Then the central figure, Britannia of course, raised up on two steps, and built to a slightly larger scale than her attendants. She has her normal accoutrements of the shield with the cross of St George, Athenian helm, mail shirt, and the lion – the lion is really rather small compared to Britannia, and would reach little above her knee were he standing up. Allegorical figures of Britannia (of which more examples on this page) can carry a trident or a spear, and here she has a bronze spear, which due to the height of the pediment, is rather short and correspondingly narrow. She too is a most muscular example of the type, noting her shoulders and particularly the bicep of her crooked arm (see the page on Warrior Women for other examples of this physical type) – the visible hand is curiously small and delicate for this arm, or even the wrist, reflecting the difficulty of combining a muscular, male arm with a female hand. The mail shirt bears a small lion’s head decoration between the breasts, and on her shoulder we see what seems to be two paws from a lionskin, though it is too worn to be sure. Below, she wears a long skirt which swirls round her waist and upwards behind, so that it may be fastened by the lions’ paws on the opposite shoulder. Her feet are bare. Next, Britannia’s other closest attendant stands, again a little lower, another Greek girl wearing a crown of olive leaves, and carrying a cornucopia of fruits, thus indicative of the good things of Trade being brought back to Britain. She seems rather more feminine than her companion.

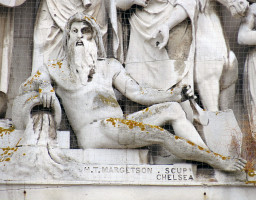

River God, and Margetson's signature.

River God, and Margetson's signature.

In front of the figure with the cornucopia reclines a river god, companion to the Mercury figure on the other side. He is unclothed, and has something of a stomach, though the effects of weathering may emphasise this by removing surface expressions of the musculature (or it might be deliberate, to indicate his well-fed prosperity). He has long hair and a beard which flows across his chest. In one hand he holds the rim of an overturned pot, with water flowing out of it; his other hand holds a ship’s rudder. The pediment is signed on the step underneath him: ‘H. T. MARGETSON . SCUPR [i.e. Sculptor] CHELSEA’.

Allegorical figures of Europe and Asia.

Allegorical figures of Europe and Asia.

Continuing to the right, we now have a rather pleasing asymmetry from the left side; on the left was the allegorical figure of North America with her bison, and the equivalent group on the right is Europe with a horse, but they are reversed, with Europe being closer in, hence next to the girl with the cornucopia, and the horse facing outwards to the right from behind her. We know she is Europe because of her generally decorous clothing, crown in the form of a castle, and the horse, which in this context is the right animal for this allegorical figure. She too is empty handed, with one hand open in an expansive gesture.

The next figure, smaller again, is Asia, or more likely, India. She is bare-breasted and has rather wild hair, indicating that she is more primitive – the same was done with the Egyptian (African) and American continents on the other side (we note that North America is, by her dress, considered as more civilised than the others, but not as much so as Europe!) – this use of states of undress to indicate the Continents is characteristic of mid and late Victorian times. Our figure of India, or Asia, stands with one arm across her body, the other resting on the brow of a small Indian elephant, marching outwards from the centre. Rather a well conceived beast this, as despite its small size relative both to girl and to the horse behind it, it conveys great heaviness and bulk through an exaggeration of the depth of the body and an alteration to the proportions to emphasise the head at the expense of the legs. For more elephant sculpture, see this page.

Allegorical figure of sea-borne trade.

Allegorical figure of sea-borne trade.

Finally, our last figure, reclining to fit into the long, narrow end of the pediment, is another unclothed man, resting his arms on parcels ready for sending by ship, as indicated by the anchor behind his shoulder, and the coil of ship’s rope which is outermost in the display.

The whole ensemble is in Portland stone, or something similar, and has experienced some erosion despite its position sheltered under the pediment. This likely accounts for some of the blankness to the expressions of the faces. The compositions, both of the individual figures and of the group as a whole, are well thought out and of merit.

Sculptural groups above the pediment: in the centre is Neptune in his chariot.

There are three groups. In the centre, seen above the crown of the pediment, is a figure of Neptune riding on a chariot, which we cannot see, pulled by three sea-horses, each with webbed feet and nice little webby wings. The figure of Neptune pulls on the reins of the centremost sea-horse, and in his other hand holds a long trident. He is unclothed apart from a piece of drapery over one arm and winding round his lower torso. Not a very athletic body is exposed, that which is left after erosion, with a rotund look and the face blank rather than severe – it may be all down to the erosion, and the exposed position suggests that this was not the cleverest place to use this easily worn stone.

The figures above and behind the corners of the pediment, in the acroterial positions, are fairly lively. On the left, a goddess of some sort seated on the prow of a boat, holding a globe, and with the other hand extended upwards as if beckoning. She is semi-clad in light drapes, tied by a belt high under the breasts, and split at the skirts, so that one leg protrudes. The exposed body is better than the face, and the whole figure is given some poignancy by the lichen growing profusely upon the upper surfaces. Behind her, a small naked putto guides the boat by the shaft leading to the rudder. Note the moustached head on the front of the boat.

On the right, a second female figure, wearing a short tunic, again gathered under the breasts, and a helm of some sort, sits sideways on what seems to be some water-chariot, an odd thing with a wheel and what seems to be caterpillar tracking, pulled by a sea horse. Arising from the water, a youthful figure is seen from the rear, presumably a mer-boy, though no tail is visible, who appears to be tugging at the rein which the female figure holds. Her other hand has been lost. Again, the female face is the weakest part of this piece.

Two lions of suitably epic size are seated (couchant, if they had been heraldic), at the sides of the portico on plinths raised somewhat above the top steps. They are notable for the profuseness of their manes, which as well as hanging down to the base, extend across the chest and underside of each beast, rather unusually and not entirely successfully. Each has one front paw stretched out flat, and the other turned on its side, again unconventional. For a discussion of lion sculpture, see this page, and lion heads are discussed on this page.

Carved lions on steps of the Portsmouth Guildhall.

Also in the Square, facing the Guildhall, is a bronze statue of Queen Victoria, subject of a separate page. We merely note here that the sculptor was Alfred Drury, and this is certainly one of the better of the innumerable public statues of the great queen.

Portsmouth's Queen Victoria statue, by Alfred Drury.

Portsmouth's Queen Victoria statue, by Alfred Drury.

Around to one side of the Guildhall, off the Square, is the large World War I Memorial, or Cenotaph, built theatre style with a semicircular wall enclosing a space in which a tall obelisk stands, with a casket on top. Two plinths to the main entrance bear figure sculpture of machine-gunners. Panels list those who fell in battle, and stone panels on the central obelisk show sculpture in low relief. The figures with machine guns are striking. One is a soldier, kneeling forward intently, feeding cartridges into his gun, with various weapons and kit around him; he is clearly in active battle. The other, a sailor, is seated on a sandbag, his gun supported on more sandbags, and resting on a funnel, with a pile of rope in front. He is taking a moment’s rest, his head sinking down upon his hand which rests atop his gun. These figures are by C. Sargeant Jagger, an important 20th Century sculptor much involved in war memorial sculpture.

Portsmouth's World War I Memorial (Cenotaph), statues by C. Sargeant Jagger.

The panels on the central obelisk include an ocean going warship in steam, with a zeppelin seen faintly in the sky; two warships moving towards a submarine; a procession of soldiers marching in step with their bayoneted guns over their shoulders; and most carefully delineated, a close-up scene, seemingly on a ship, showing a group of five seamen in overalls and hoods involved in loading and aiming a big gun.

Sculpture in low relief: panels on the Cenotaph.

Nearby is another, smaller obelisk, with lists of names around a short outer wall, which is the civic memorial to World War II. It is of recent origin (dated 2005), and does not include figure sculpture, but has a sculpted wreath with an anchor, a symbol fo the airforce with an eagle in relief, another symbol with a lion on top of a crown over crossed swords, etc.

Also in Portsmouth: Queen Victoria Statue, by Alfred Drury // King's Theatre, Albert Road

Statues in English towns // Pediment sculpture.

Alfred Drury // Sculpture pages

Visits to this page from 11 Apr 2014: 5,416 since 24 September 2024