The Martyrs' Memorial, Oxford

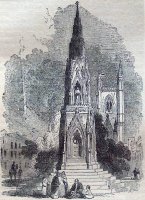

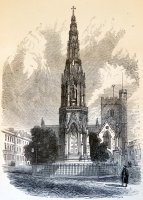

Two views of the Martyrs' Memorial.

The Martyrs' Memorial in Oxford is a tall, early Victorian shrine in the style of the 14th Century Eleanor Crosses, designed by the architects Gilbert Scott and Moffatt, put up in 1840, and with statues of the three martyrs by the sculptor Henry Weekes.

The Martyrs' Memorial in Oxford stands in Magdalen Street Street at the south end of St Giles Street, opposite the Randolph Hotel on the corner of Beaumont Street wherein is the Ashmolean Museum. It is a tall, hexagonal Gothic shrine in the style of the 13th or 14th Centuries, and at first sight looks very similar to the Eleanor Cross at Waltham (see this page) - no accident, for the Memorial committee which launched the architectural competition in 1840 to design it asked competitors to have the Eleanor crosses in mind. The partnership of Scott and Moffatt won the competition: this was Sir George Gilbert Scott, who later was to be one of the most significant Victorian Gothic architects, and his partner William B. Moffatt (1812-1887). A bit more on them further down. The memorial was complete by 1843.

The Martyrs' Memorial is built of several stages, the base being raised up on hexagonal steps. The largest, lower stage consists of blind Gothic windows, with painted shields of arms, and minor repeating sculptural detailing, solid and blocky overall. Above this, the second stage has the three alcoves within which stand the statues of the martyrs: Thomas Cranmer, Thomas Ridley, and Hugh Latimer. Ridley and Latimer were Anglican bishops who were burnt at the stake very close to the site of the memorial, in 1555; Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, was burnt a few months later in 1556.

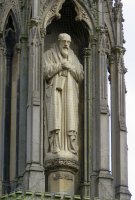

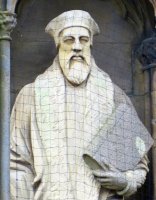

Statues of the Martyrs by Henry Weekes: Latimer, Cranmer, Ridley.

The three statues, in white stone, stand on short pillars or pedestals bearing their names, and with leafy capitals. They are tucked well in their niches, so have survived 180-odd years of weather and pollution well. There is a certain similarity between them - three bearded, moustached clerics in long robes of the same period - but enough variation to provide interest. Cranmer holds a heavy book in the crook of his left arm, wears the distinctive cap familiar from his portraits, and as an archbishop, has a very broad furred edge to his robes. His gaze is directed outwards, his eyes narrowed in a piercing, purposeful gaze.

Latimer, much older than the others, is rather bald, his head stooped rather than bowed, his hands across one another on his chest, and a book under his robe. Ridley also has crossed hands, his arms however downward rather than upward, and directs his gaze upwards towards heaven.

Detail of carving on the memorial.

The sculptor was Henry Weekes, and the Martyrs' Memorial statues, added to the memorial in 1841, are fair examples of his earlier work. Sir Francis Chantrey, to whom Weekes was assistant in his later years, supervised the designs and workings of the statues, dying in that same year. Weekes has another statue in Oxford which can be seen at close hand: that of William Harvey in the University Museum.

The statues are on the second stage of the shrine-like design, and above each of them rises a crocketed (toothed) pinnacle, near as tall as the niches below. While the statue level is hexagonal, with the three niches and slighter blank niches between them, the pinnacles serve to hide the change to a thinner central core, with blind windows above, and successively more delicate, thin portions rising to a small cross on the summit. Strictly speaking, the memorial also includes the aisle on the north side of St Mary Magdalen Church by it: the original intent of the memorial committee had been to build a new church, but it being not possible to find a nearby place in the centre of Oxford (the actual martyrdom site is within Broad Street), the extension to include a 'Martyrs' aisle' in St Mary Magdalen was undertaken, a little later than the memorial, and again by the architects Scott and Moffat. This can no longer be readily seen from the memorial side, due to the large trees in the graveyard, but can be viewed from the little street behind the Church next to Balliol College (Magdalen Street East): we see three tall, three-light windows, separated by buttresses bearing coats of arms of the respective bishops, and towards the main road (Broad Street), a new north porch.

Martyrs' Memorial views, 1860s and 1870s.

Gilbert Scott and Moffatt were pupils of an architect called James Edmeston, rather obscure today, with Moffatt originally acting as assistant to Gilbert Scott, and the partnership set up formally in 1838, mostly to design workhouses put up under the Poor Law reform act, with each of them also undertaking their own separate architectural work. The partnership was highly productive at the beginning of the 1840s, when they won the competition for the Martyrs' Memorial, but was dissolved by Gilbert Scott in 1846. While Scott went on to fame and fortune mostly building churches, Moffatt was incautious with money, and though he had some success, notably with the Taunton Shire Hall, Somerset, which is a pale stone Tudor Gothic style building of some considerable character, he went bust in 1860, and a short imprisonment seems never to have ended his career as an architect. There are a variety of Victorian Gothic shrines and memorials, with Gilbert Scott himself designing the greatest of them all, to Prince Albert, put up more than 20 years later (see this page).

St Mary Magdalen Church.

Back to the Church, we may note that the south aisle, of 14th Century date, had a restoration and rebuilding at the same time, by the architect Edward Blore, at that time much more well-established than Gilbert Scott, Surveyor of the Fabric of Westminster Abbey and restorer of Lambeth Palace. On the exterior of that aisle, again rather obscured by trees, are four statues, entitled Maria [the Virgin Mary], Elias [the prophet Elijah], Ricardus [Richard I], and Hugo [Bishop Hugh of Lincoln, who enlarged the Church in 1194] - these were only emplaced in 1913. I don’t know who the sculptor was, but they are competent architectural pieces rather than purporting to be more, and despite niches and trees, already rather worn.

Also noted on these pages in Oxford: Physick Garden gate, with 17th Century sculpture