There have been many tellings of the story and survival of the Eleanor Crosses, but it is justified to write something on these pages from a sculptural point of view.

By way of brief background, the story of Queen Eleanor is a touching and romantic one. Eleanor of Castile was married to the future Edward I when he was 15 and she but 10, a political marriage to end the enmity between King Henry III and Alphonso of Spain. She grew up in France before being united with her husband in 1265, when she was able to settle in England. Unusually for a marriage of state, perhaps, they fell deeply in love with one another. Eleanor travelled with Edward on Crusade in 1270, nursing him to health when he was wounded by an assassination attempt in Acre. After a sojourn in France, the couple returned to England for Edward to be crowned King in 1273, after the death of Henry III. The absence of Llewellyn, Prince of Wales from the coronation was the signal for a long war to put down his insurrection, leading eventually to his death – hence ‘Llewellyn the last’. Some years of peace followed, until in 1290 the youthful Queen of Scotland died. Edward, sensing opportunity, went northwards, with Eleanor coming at slower pace behind as she had done on previous campaigns. He reached the Scottish borders to hear that his queen had caught a fever while travelling near Grantham, Lincolnshire, and immediately put aside his Scottish adventure to ride back to her – only to find she had died, aged just 47. It took 13 days for the funeral procession to reach London, and at each stage where they rested, the King ordered a cross be erected in memory of Eleanor – the Eleanor Crosses.

There seem to have been up to 15 such stops, and the precise route of the procession, and the number of crosses, is not certain. They have been supposed to be at Hardeby, Lincoln, Newark, Leicester, Geddington, Northampton, Stony Stratford, Dunstable, St Albans, Waltham, Cheapside, and Charing by Westminster. An alternative account supposes Stamford and Grantham itself rather than Newark and Leicester, and Woburn has also been suggested.

Regardless, three crosses survive, at Geddington, near Kettering in Northamptonshire, at Hardingstone near Northampton (this site has a separate page on other sculptural interest in Northampton), and at Waltham. On these crosses, in total we have 10 statues of Eleanor, in various poses and drapery. At the end of the journey, though the monuments have gone, we have some account and illustration of the crosses at Cheapside and Charing Cross, and the effigy of Queen Eleanor in Westminster Abbey remains today.

It is a triangular cross, raised on eight steps, with three storeys, standing 42 ft high overall. A description in the early Victorian era noted that the solid lowest section had on each face six panels, entirely carved with ornamental sculpture, and with the shield of arms of England, Castile, Leon, and Ponthieu. Above this are castellations, then a pillared second storey with canopies within which are three statues of the queen, somewhat obscured by pillars. The statues show the Queen as ‘very beautiful, clothed in a long flowing robe, and a veil which descends to her shoulders, over which is a coronet, the flowers of which are now quite effaced. The air of the head in these figures is graceful, and drapery falls with natural though too minute folds, and the hands and feet are well drawn.’ The statues were seen as bearing so great a resemblance to those of the Italian school ‘that it is likely that Edward had artists of that nation in his service.’ The third level had an assemblage of slender pinnacles and finials ornamented with oak leaves and flowers at top. The summit had already been lost, but presumably consisted of a spire and cross.

The stone is of local origin, and while indeed graceful, the pose of the figures is rather straight and stiff.

It consists of three stories, the first octagonal, 14ft high, with arches on each side, each of these being divided into two by a mullion, with shields of coats of arms – Leon and Castile, England and Ponthieu. Below each are high relief sculptures of a book on a desk. The second level, some 12 ft high, is octagonal, and bears four deep niches with figures of Queen Eleanor, each 6ft high, and crowned. There are, or were, traces of a sceptre in her right hand, while the left is denuded but presumably either held a globe or lay on her breast. The third, upper level of the monument is square, 8ft high, with more Gothic arches. A restoration of 1713 added a sundial, a new cross on top, and a marble tablet to commemorate the changes, leading to the cross later being lamented as ‘much disfigured by the repairs executed by officious and ignorant individuals’.

Records of the Eleanor Trustees record that the sculptor was a certain William of Ireland, a mason-carver. But there were five, rather than four figures carved in 1292 and ‘sent down to the cross at Northampton and elsewhere’. The figures are more lively than the Geddington Eleanors, both in the pose, which is more naturalistic, and in the complexity and hang of the draperies, which can be linked to other medieval work at Salisbury Cathedral and elsewhere.

See this page for more pictures.

Waltham Cross, before and after restoration.

Waltham Cross, before and after restoration.

The figures on the Eleanor Cross at Waltham are considered the finest (those on the Cross today are replicas, the originals having been placed in the Victoria & Albert Museum), and are closely allied in their naturalistic style to those of Northampton. The Eleanor Trustees records state that the carver was Alexander of Abingdon, mentioned also as having supplied figures of bronze, and also responsible for the Charing Cross figures. Alexander of Abingdon was a goldsmith, a caster in bronze and an imager, a maker of church figures. The following description of her is from the 1840s: ‘The drapery of the figures – an under-gown, or kirle, made high in the neck, with close sleeves, fell in graceful and easy folds to the feet, forming a train. Over this was worn a robe with full fur sleeves. …Her neck and shoulders unencumbered with a gorget [balaclava-like head covering], and only ornamented by the wavy ringlets of her beautiful hair.’ Note also the bend to the leg, giving a curve of pose similar to, but more subtle, than the Northampton figures. These are the figures of Queen Eleanor shown at the top of this page. All very fitting - Eleanor and Edward, according to Strickland’s Lives of the Queens of England, encouraged sculpture, architecture and casting in brass and bronze, and an increase in woodcarving, including by patronising and inducing foreign artists to come to England, amongst whom was Cavallini.

Waltham Cross was rather damaged by carriages and encroachment of houses to the point where a roof from one house was said to have leaned against one of the statues of the Queen. The cross was repaired after the Society of Antiquaries called attention to its poor condition, and the local gentry subscribed to repair and restore it, this work being done some while later to the design and under the direction of WB Clarke.

More pictures on this page.

So much for the surviving Eleanor Crosses. We have a good account of the two in London:

Cheapside Cross (West Cheap cross) stood in middle of road facing Wood Street,and was built in 1290 by Master Michael, a mason of Canterbury. Again with three levels, in this case each supported by 8 slender columns. The lowest story was suggested as 20 ft high, with the upper storeys of ten and six ft high. It was surmised that the lower storey originally had a statue of a contemporary pope, with above, the four apostles, and the Virgin and child. Highest of all were four standing figures of Queen Eleanor, and above that, the cross with a dove. These features can be discerned in the first view above. A rebuild of 1441 added a drinking fountain, and some wooden structure around the old cross, covered with lead and gilt – this is perhaps the structure shown in Ralph Aggas’s Map. Further alterations followed, but from the time of Elizabeth, it was attacked, as other crosses were elsewhere, for its Popish imagery. First the Virgin was denuded of her child, and other sculpture on the monument, described as being of the Resurrection, Christ and Edward the Confessor, were mutilated. After further repairs, to the Virgin at least, that figure was apparently replaced for a time by the Goddess Diana, ‘a woman for the most part naked, and water, conveyed from the Thames, filtering from her naked breasts, but oftentime dried up’. A further restoration, with the Popish images replaced by effigies of ‘apostles, Kings and Prelates and iron railings added (above right), did not suffice, and the monument was attacked again after 1641 and finally pulled down in 1647, ‘and the leaden figures of the prelates burnt’. A contemporary publication adds that it was built of ‘lead, iron and stone. Some say that divers of the crowns and sceptres are of silver, besides the rich gold that [it] was gilded with’.

Three or four oft-reproduced and re-engraved views survive. And a couple of fragments showing the coats of arms are in the collections of the London Museum.

End of the Cheapside Cross, 1647.

End of the Cheapside Cross, 1647.

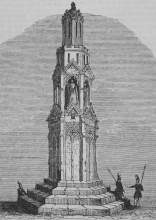

Views of Charing Cross, various sources, perhaps freely copied from each other.

Charing Cross – the name itself has been suggested as being from ‘Chere reine’, Edward I’s term of endearment for Eleanor, though others, less sentimental and perhaps with more of the right of it, say ‘Charing’ came from an Anglo-Saxon word referring to a turn of the road. The cross stood not where the 19th Century one is, but where Charles I now stands to the south side of Trafalgar Square. The first cross was originally of wood, but then built in stone by Richard de Crundale, and after his death by a son or brother, Roger de Crundale, though the statues of Eleanor, I think, were by Alexander of Abingdon. The structure was made from Caen stone, with steps of smooth marble. It was based on an octagonal design, thus with eight figures of Eleanor on an upper stage, and the most elaborate of the Eleanor crosses. Parliament voted to pull it down in 1643, and demolition took place in 1647. Apparently some of the stone was used in pavings in Whitehall.

The Victorian Charing Cross was the work of the architect E. M. Barry, and the not particularly well known Thomas Earp was the sculptor. The design was loosely based on the extant images of the old cross, and thereby has several tiers, and an octagonal symmetry, to give eightm statues of Queen Eleanor at the third level. If anything, the architect has made the structure even more vertiginous than the surviving medieval crosses, and there is of course more ornament, including extra figures in the form of the small angels kneeling below the statues of the Queen against each pillar. So far as Earp's statues go, each Queen Eleanor is different, but slightly so, and the richness of the folds in the drapery is more than the medieval figures. The pose is standing fairly straight, with the head leaning forward slightly, so as to make something of a connection with the viewers below, and imparting a certain chasteness and modesty to the subject; a sense of piety exudes from the whole.

1880s view of the Victorian Charing Cross, and two of Earp's Queen Eleanors.

1880s view of the Victorian Charing Cross, and two of Earp's Queen Eleanors.

Regarding the other medieval Eleanor Crosses, only the smallest fragments and short descriptions exist, and we shall not linger on them, but just note two of examples: Stukely, Secretary to the Society of Antiquarians, wrote in 1757 that the cross at Grantham ‘stood in the open place in the London road; and I saw a stone carved with foliage work, and said to be part of it, and I believe it, seeming to that sort of work’; and an account of Stamford written in 1646 referred to of ‘an ancient cross of freestone, of a very curious fabric, having many scutcheons insculpted in the stone about it, as the arms of Castile and Leon quartered, being the paternal coat of the King of Spain; and divers other hatchments beloinging to that crown, which envious Time hath so defaced that only the ruins appear to my eye, and therefore are not the be described by my pen. This cross was called Queen’s Cross, and erected by King Edward I in memory of Eleanor his wife.’

Although not the subject of this page, we may note that William Torel was the sculptor of the bronze Queen Eleanor effigy in Westminster Abbey, and in 1291 was paid £113, 6s, 8d, according to the Eleanor Trustees’ accounts, for this statue, that of King Henry III, and another figure at Lincoln – this last was a second bronze of Queen Eleanor, destroyed by Parliamentarians in the usual way. However, some small portion of the chapel in which the effigy lay still remains at the East end of the Choir in the cathedral – alas, I did not know to look for it the last time I visited. The surviving Westminster Abbey Eleanor is ‘a beautiful figure of the Queen, of copper [described also as ‘brass’ or bronze elsewhere] gilt, on a tablet of the same. The left hand, laid lightly on the breast, holds the collar; while the right falls gracefully on the drapery, and perhaps held the sceptre. The head is adorned with a coronet of fleur-de-lis and trefoils, under which the hair falls in ringlets. The drapery consists of a close tunic and mantle, the latter spreading from the shoulders, meeting again about the knees and covering the feet.’ The drapery, we may remark, has been strongly linked to earlier medieval figures in stone in a style popular in the south-west of the country, at the cathedrals of Exeter, Salisbury and Lichfield.

Waltham Cross // Hardingstone Cross // Another Cross - Bristol High Cross

Sculpture pages // Trafalgar Square

Visits to this page from 1 Mar 2015: 3,953 since 25 September 2024