This page notes several outdoor statues in Gloucester, from the 17th Century to modern times, which can be conveniently seen in the course of a gentle walk. We start with Gloucester Park, just south and east of the city centre. The park is of reasonable size, and takes about 10 minutes to walk across, rather longer around the perimeter, and our first statue, on the eastern side, is that of Queen Anne.

The statue is on the east side of Gloucester Park, adjacent to Trier Way. Queen Anne is standing, a slender figure with her arms in front of her on a tall square plinth. The statue is of limestone, pitted and much decayed, and little detail is left: the hands are gone, the face reduced to an oval with an indication of the main features. We can still see that she wore a wide-shouldered top, narrowing to a flatteringly slight waist, then a long, decorated skirt down to the ground below. A repeating design of flowers survives in part on the skirt, a remnant of the flow of the drapery around her feet, waist, and some cloak behind, but it is only in the overall pose, elegant and light, that we glimpse a remnant of the sculptor’s original creation.

Queen Anne, by John Ricketts the Elder.

A sign by the statue tells us it was erected in 1712 near the top of Southgate Street, and moved several times before arriving in Gloucester Park in 1865: the trees around give some shelter today, but I would think that most of the weathering has arisen because of its relatively exposed position, especially when the trees were saplings.

John Ricketts the Elder, who became a Freeman of the City of Gloucester in 1711 in return for making this statue, founded a dynasty of sculptors in the city through to the end of the 18th Century. He made the monument to William Lisle, d.1723, in Gloucester Cathedral, with a bust, which allows us to see the quality of his work undamaged by time.

Proceeding north from the Queen Anne Statue brings us to the north east corner of Gloucester Park, where Trier Way meets Park Road, and here is the Gloucester Regiment War Memorial (First World War). It consists of an obelisk raised on two shallow steps, with a sphinx on top and a bronze wreath on the front above the inscription. The sphinx has a naturalistic leonine body, and a large Egyptian headdress, making it appear rather short when viewed side-on. For more sculptures of sphinxes, see this page.

Gloucester Regiment War Memorial, Gloucester Park.

Continuing along the perimeter of the park, we walk westwards, parallel to Park Road, on which stands the Gloucester United Reformed Church, dated 1871. It is a fine Victorian Gothic building with polychrome bricks, a stumpy tower, and the entrance, raised up on many steps, with a modelled terra cotta scene in the tympanum of a preacher and many listeners, in the style of George Tinworth. High above, a too-small roundel has a decayed carving of a fruiting tree and flames or some such (see picture at top of page).

Gloucester United Reformed Church, and sculpture in tympanum.

A couple of minutes stroll further, the statue of Robert Raikes is at the north west corner of Gloucester Park, closest to the town centre. The bronze statue of the wealthy Gloucester philanthropist, whose most notable cause was to start the Sunday School movement, is in a standing pose on a tall plinth, head downward towards his viewer, gesturing freely with one hand towards the open book held in his other one. He wears a knee-length buttoned coat, and breeches above tall stockings to show his legs to what was considered advantage in his times. The sculptor was Thomas Brock, one of the most eminent sculptors of Victorian and Edwardian times, and this statue reproduces the one in Victoria Embankment Gardens in London (picture below right).

Robert Raikes, by Thomas Brock, Gloucester and London.

The Park also contains some Victorian furnishings: near to the Raikes memorial is a fountain, with vast stone lower bowl, and a smaller upper splashbowl held up by Classical dolphins with twisted tails, also in stone. Also a typical Victorian bandstand, and a small Tudor-style ornamental hut, now a café.

Going in to the City, the compact centre is divided into northern and southern halves by Eastgate and Westgate Street, and on Westgate Street, opposite Upper Quay Street the coloured carving of a coat of arms of Gloucester may be seen up on a wall by the entrance to Three Cocks Lane. The heraldic shield is within a cartouche carved with flamboyant scrolling, not that complex to look at, but perfectly proportioned. The supporters to each side consist of a pair of naked cherubs, each seated on a heraldic beast: a lion on one side, and unicorn on the other. These beasts are a weakness, especially the unicorn, perhaps mainly due to the painting. By contrast the cherubs are naturalistic in their carving, and better coloured, though such things are an acquired taste (I have never quite acquired it, but see this page). The public authorities have sensibly placed the arms in a recess with a frame, and under a projecting roof, to preserve them from the worst of the weather. A note on the wall states that the armorial bearings were carved in 1745 by Thomas Ricketts, for the front of the old Booth Hall in Westgate Street, which was demolished in 1957, the arms being emplaced in their current position in 1961. There were two Thomas Ricketts, father and son, respectively the third and fourth generation of the Gloucester firm of masons founded by John Ricketts the Elder who made the Queen Anne statue we noted above.

Thomas Ricketts' cherubic coat of arms.

Three Cocks Lane itself is an unprepossessing passage, leading north and becoming St Mary’s Square, and the statue is by some modern houses down a walkway to the left before the open space of the Square is reached – not something the casual visitor to Gloucester is likely to stumble across by accident. The statue is as ruined as the Queen Anne in Gloucester Park, but still vaguely recognisable as Charles II, with his long hair to the sides, coronet on top. For the rest, we can make out his bulky robes, with some sort of mantle above, thick cloth wound about his middle, tunic, and stockinged legs, with light footware. But all is battered, the face is mostly gone, and the left hand side of the figure as the viewer observes it has been sheared off, including the arm on that side. The date the statue was made, according to the information plaque, was 1662, and it was originally in Southgate Street in the Wheat Market, later lost, and set up in its current position in 1960. The sculptor, Stephen Baldwyn, was of a Gloucester family of stonemasons. The previous year to the Gloucester statue, he made a similar statue of Charles II for Worcester – that one became worn and was repaired by Thomas White half a century later, and still survives on the exterior of the Worcester Guildhall. Looking at that, we see that the much more damaged Gloucester example is a similarly composed figure but reflected right to left.

Stephen Baldwyn's Charles II, and Worcester version.

Stephen Baldwyn's Charles II, and Worcester version.

We continue into St Mary’s Square – this St Mary being St Mary de Lode. There stands the shrinelike monument to John Hooper, Bishop of Gloucester, martyred 1555. A bronze plaque notes that the monument was erected by public subscription in 1857, ‘on the site of a smaller one, the gift of James Wealand of Bangor, Ireland’.

The Gothic surround is of more interest than the statue itself, maybe 35 ft high or more, with square base, pillars at the corners rising to pinnacles, a tall, pointy gable over each side, and then a central spire, much crocketed, rising to a cross and weathervane. There has been some small recarving, adding strange little beastlike heads not out of keeping with the original sculpture. The central statue itself, of pale marble, shows Bishop Hooper standing in lengthy clerical garb, wide-sleeved, furred, and closed at the front without belt or noticeable buttons. He has a long and somewhat hollow-cheeked face, much bewhiskered, and this Byzantine look is echoed in the style of the drapery, particularly in the folds across his forward leg. He carries a Liber Vitae book (memorial book recording those entering into fraternity with the Church), his other hand held forward in greeting or benediction.

We can pass through St Mary’s Gate to the east into the Cathedral Precinct, College Green, where is our next piece of sculpture.

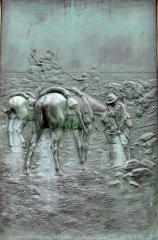

To the west of the Cathedral stands a great cross on a tiered octagonal plinth, around which are the names of the fallen Gloucester Hussars in World War I, and four panels with sculpture by Adrian Jones. Adrian Jones, an important sculptor of the early 20th Century, was himself in the army, and loved above all things horses: he had a large output of equestrian subjects. War memorials naturally lended themselves to his interest in horses, as here. Each of the four panels shows the scene of a different battle, named underneath. But the images are not of actual combat. One shows soldiers climbing a rocky hill, their leader pointing forward towards the enemy, and all three others include horses, the best of which has a column of them cantering down a hillside. Typical, good examples of Adrian Jones’s work.

Gloucester Hussars Monument, with panels by Adrian Jones.

A low, long panel was added to the base of the memorial after the Second World War showing a group of soldiers clustered around a tank, well composed, but with some weakness to the faces of the soldiers, though the tank itself is splendid and there is much good detail. The sculptor signs in the lower right hand corner as Edward Payne, 1950. He needs to be distinguished from others by this name, including a 19th Century Welsh sculptor, and a modern one. I would think he would be the stained glass worker Edward Raymond Payne (1906-1991), who was a Gloucester artist, born in Birmingham and the son of Edith Gere, an Arts and Crafts illustrator and painter. But I know of no other sculpture by him – it may be that he designed the piece in mural form and it was made as a piece of sculpture with the aid of some sculptor colleague.

Edward Payne's tank sculpture, added 1950.

This page does not cover inside the Cathedral or the various churches in the city, but before leaving the Cathedral Precinct, we may note the statues around the entrance porch. There are a dozen in all, six above the portico, being the four evangelists, St Peter and St Paul, and three saints on each side, including a minor Anglo Saxon king called Osric, who is recorded as having founded the original monastery on the site of Gloucester Cathedral in the latter 7th Century: a later tomb to him is within the Cathedral.

James Redfern's statues of saints for Gloucester Cathedral.

The statues, in stone, are clearly of the later 19th Century, and extremely competent, with interesting poses and drapery, giving a fair variety among a group of essentially similar bearded clerics of a certain age. They stand within niches, ornately carved with little vaulted ceilings above each saint’s head, tall elaborately crocketed spires above, and little gargoyle heads beneath. The sculptor was James Redfern, who seems to have specialised in ecclesiastical sculpture, and who also carved the statues on the exterior of Salisbury Cathedral. These ones date from a restoration of 1871, so around 15 years later than the Bishop Hooper monument.

On Eastgate Street is the Eastgate shopping centre, and the entrance to this is a magnificent Victorian Greek portico, dated 1856, which once formed the entrance the Eastgate Market. The portico is of truly generous proportions, and made in a beautiful pale stone (Bathston). Four attached pillars rise to two storeys high, with graceful arches between them, each with a carved keystone and spandrels (triangular shapes above the arches). The keystones include a male and a female head and a central shield of arms, and the spandrels have low relief carving of fish, fowl, and centrally, fruit issuing from cornucopias. The vaguely Composite capitals of the pillars bear little flowers. Above is a broad pediment, containing a clock, surrounded by a carved wreath, supported on a block bearing the legend 'The Earth is the Lord's, and the Fulness Thereof' - very appropriate for a market - and to the sides are seated figures, male and female. The man, old, bearded and wearing a long shroud, is Time, and stares at his hourglass, his other hand holding his scythe. The woman on the other side seems to be an allegory of Abundance, for she has a cornucopia by her side, and holds frut - grapes, a melon, some other unidentifiable but succulent things. Although Classically dressed, she wears a broad, peasant's slipper on her visible foot, and there is a lack of sureness in the carving, above all in her (damaged) arm and hand. The carving was carried out by a certain Henry Frith of Gloucester (1820-1863), and the whole edifice is the work of William Jones and Son, also of Gloucester.

Eastgate Market Portico, carved by Henry Frith of Gloucester.

Almost opposite, we may note the former Guildhall, now a branch of TSB, in Renaissance style, 5 bays wide, with balustrade at first floor level, pillars on the floor above, and on the uppermost floor, a frieze of pairs of cherubs each with a central round window. The carving is rather good in the detail, though the proportions of the figures again betray a provincial sculptor. I do not know who carved this, but the architect of the Guildhall was G. H. Hunt, and the building was erected in 1890-92.

Guildhall, 1890-92, with cherubs.

Our final statue is a modern one. Gloucester was named Colonia Nerviana Glevensis after the ancient Roman Emperor Marcus Cocceius Nerva, recognised by the City authorities by a bronze equestrian statue of him, put up in 1997. Nerva is shown seated on a prancing horse, one hand on the reins, the other raised in a Roman salute. He wears the customary Roman military costume with breastplate and short tucked-in cloak above a toga, bare legs and sandals. His face features a large hooked nose, not particularly a feature of surviving portrait sculpture of Nerva, but very much so on some of the coinage of the time, and it is to such coins that the sculptor must have looked in creating this piece. The work shows the unfinished roughness favoured by many modern sculptors, but is a worthy sculpture, particularly in some of the musculature of the horse.

Emperor Nerva, by Anthony Stones, 1997

Anthony Stones (1934-2016) was the sculptor; a native of Glossop in Derbyshire, who studied in Manchester before emigrating with his family to New Zealand in the 1950s, returning to England in the 1980s, and dividing his time between Oxfordshire, New Zealand and China in his later years. He is best known for portrait busts, and public sculpture in New Zealand.

Close by is the beautiful medieval church of St Mary de Crypt, not covered here, except to note the Lamb of God carved in the tympanum over the doorway.

Statues in some English towns // Sculpture pages

Visits to this page from 29 May 2017: 9,882