St Mary Magdalene, Reigate is a large, broad church, of great age and much changed over the centuries. It has a square tower, with battlements, not that high at four stages given the length and breadth of the body of the Church, but appearing so from the roadside, which is lower. The tower is late 14th Century apparently, concealed behind a 19th Century refacing of Bath stone.

Inside the breadth of the Church is apparent, with the nave separated from the aisles by an arcade of arches on columns which are not parallel on each side. This, and the differing treatment of the columns, are a clue to the enlargements and alterations over the years, with restorations in the 19th Century first obliterating much of the older work, and then, under the architect George Gilbert Scott Junior, son of Sir George Gilbert Scott, somewhat redressed from the late 1870s - a very heavy restoration of the Church, which was at the point of collapsing. It was he who faced the Bath stone on the tower, replacing the original Reigate stone. The north transept was built as late as 1908, by the brother of George Gilbert Scott Jr, John Oldrid Scott, a notable church architect in his own right.

The principal monuments are at the altar end and in a chapel on the northern side, with the balance mostly along the walls of the aisles. There is one rich and flamboyant 18th Century monument in Reigate Church, with five full-size marble figures, plus cherubs and ornament, to Richard Ladbroke, which is worth a visit in itself. And more ancient, a curious construction, much altered, comprising two linked tombs, each with two reclining figures of alabaster – the Elyots (or Elyotts) and Bludders. Also there is a kneeler monument of some size in a niche, who is Katherine Elyott. And around a score of other panels from the 18th and 19th Century, with three nudging into the 20th Century, so giving a fair range of the more minor monuments of the times.

View of the interior of the Church.

View of the interior of the Church.

We start with the grand monuments to the Elyots and to Richard Ladbroke, and then cover the rest:

The Victoria County History volumes for Surrey note that this is the remains of a larger tomb: ‘The Elyots [or Elyotts] of Reigate and Albury, who were connected by marriage with the Skinners, left a tomb which till 1845 stood against the north wall of the sacrarium, but was then taken down, its beautiful canopy destroyed, and the remains, including the recumbent figures of the two Richard Elyots, father and son, who lived at the mansion called the Lodge and died respectively in 1608 and 1612, placed in the north chancel. The statue of the father, with hands joined in prayer, is a good piece of work. Upon the front of this tomb were the kneeling figures of Rachel, widow of Richard Elyot, senior, daughter of Matthew Poyntz, of Alderley, Gloucestershire, and their six surviving daughters’

So what do we have today? Better than mere remains, for there are the two grand effigies of the knights, surrounded by alabaster, and with a large roundel bearing the shield of arms. The whole is a bench-like construction, with a lower fore-portion, on which is a bed with the elder Richard Elyot lying recumbent, and behind this, raised up, is the figure of the Richard Elyot the Younger, lying on his side, head propped somewhat uncomfortably on his elbow. The two make a fine group.

Elyot and Bludder tombs, early 17th Century.

Elyot and Bludder tombs, early 17th Century.

The younger Richard Elyot is shown as a rather aged figure, the skull-like nature of the head accentuated by the swept-back hair, which draws attention to the roundness of the forehead and the roundness of the eye-sockets, and a beardless chin above a ruff, with the neck tight-bound underneath, so making the head appear rather detached from the armoured upper body. This torso has grand shoulders in plate armour, and the arm the figure leans on shows well his broad cuff, so rather a powerful and dashing appearance contrasting with the weak Elizabethan head above. But then the lower body, with a puffed-out pantaloon style construction, only partly squashed down underneath his hip and overall disturbingly bulky, making his rather thin legs below look emaciated by comparison. Although on his side, there is no appearance of restfulness or comfort in the pose of those legs. Not a great success overall.

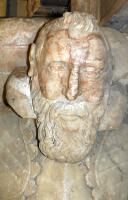

The elder Richard Elyot, as the quote above indicates, is far better. The view we have from the front is a profile one, and we see a powerful body, well-proportioned, in tight-fitting armour emphasising the vigour and strength of the limbs beneath, above which the head is that of a patriarch, with flowing beard and sagacious features. His head is raised up on two cushions, and he lies easily, hands in prayer, damaged but what is left showing some character, and with thighs and lower legs of far more muscularity than his hapless son; the feet are missing. Leaning over to look more closely at the portrait from above is a rather disconcerting experience, for along with traces of colour to hair and beard, the face is made of a red-veined marble or alabaster which gives the impression of an ancient, ruined skin with blood vessels running underneath; together with the eyes, one a little lower and less open than the other, and the gnarled nose, it is disturbingly lifelike - see picture at top of page, far right (you will need to click to enlarge).

Richard Elyot effigies, father and son.

Richard Elyot effigies, father and son.

On the sill at the top of the monument are the remains of small, battered figures, who are likely among the daughters noted in the quote above, with the largest being perhaps the wife. However, one at least belongs to the monument described below, to Thomas and Mary Bludder. In front of the base of the tomb is the black marble inscribed panel, with a Latin inscription, still perfectly readable more than four hundred years after it was made.

Jammed up against the left hand side of this monument we have the second one, to Sir Thomas Bludder and his wife Mary, a box-like affair with surviving outer pillars in polished dark marble, and a canopy or roof above, and two full-length recumbent figures underneath on top of a chest tomb. Behind, on the inner wall of the recess, is their inscription, showing the likely position of the Elyott panel before that monument was mutilated; a second panel is on the front too. The figures of the couple lie on their backs next to one another, he a little taller, and in front, she behind. As for the younger Richard Elyot, Sir Thomas is wearing armour with an oversized garment over waist and upper legs, part trouser, part pantaloon, and with articulated armour in front; It looks odd, but not so much so as the younger Elyot. His wife wears a long cloak over arms, body and feet, perhaps a shroud, and a good on her head. She has a large ruff, and her clothing underneath the outer wrap is a long shapeless garment with many folds, typical of kneeler monuments of the time. Both figures are damaged, having lost their praying hands, and with wear to the faces, she much more than he. The Victoria County History refers to the ‘diminutive figure of a female child, removed from its position at its parents’ feet on this monument’, so that one of the figures above the Elyott monument presumably belongs to this one.

Sir Thomas and Mary Bludder, d.1618.

Katherine Elyot. d.1623, fifth daughter of Richard Elyot the Elder, is in the south chapel, in a pointed niche with the dark inscribed panel from the monument is in front, but which has nothing to do with her original surround: this would have been Classical of course. The Victoria County History mentions her tomb ‘with a canopy of alabaster or coloured freestone’, which was the norm for such pieces; she would likely have been under a round-headed arch, with pillars to the sides. Her stance is that of a conventional kneeler, of the type found from Tudor through to beyond the end of Elizabethan times. Thus we see her in profile, hands raised in prayer, kneeling on a tasselled cushion. Her head in this case is bare, showing wavy hair tied close to the scalp, a young, rather plump face, and she wears a very large ruff. While her loose shirt, with frills at the cuff, shows some shape to her body, her skirt is one of those unflattering shapeless things supported by a cage-like affair, showing no hint of legs underneath; a broad ribbon of cloth is carved hanging from one arm, down, and folded on the ground. In front of her lies a block with her prayer book on a separate book rest upon it; this block would originally have been upright and formed the normal prayer-desk found in such monuments. Some paint still remains, but not much; the hands look to have been recut rather than decayed to their current simplified form.

Before leaving these monuments, we may note that in front of the altar set into the floor are several slabs, with and without brass inscriptions, to others of the Elyott and Bludder families.

Now to the grandest monument in the Church, to Richard Ladbroke. It is centred on the reclining figure of Ladbroke, dressed in Roman toga and really rather grand in appearance. His face is anything but Roman, and he wears a periwig, but his powerfully muscled chest and limbs fit with the Roman martial tradition. One hand rests on a skull and holds a book open with one finger, the other holds a crown, combining learning and majesty with an emblem of death. Behind him, a tall obelisk bears the inscription, and upon it rests a cartouche of arms, once painted doubtless, now blank. On either side are tall pillars of brecciated marble, with Corinthian capitals, holding up an entirely broken, curved pediment, with raised central portion, a Baroque completion of a structure which is essentially based on a Roman triumphal arch. On the wings of the pediment are reclining angels, one with a trumpet, the other perhaps a bow; between them is a circle of winged cherub heads within a sunburst. At the top, on the mini pediment topping off the monument, is a central pot and two unclad putti. To the sides of the main structure are wings, with pilasters to the sides, so framing the outer niches of the tripartite arch. Here stand two more girls, full sized statues with heads turned slightly inwards to draw the eye to the subject of the monument reclining between them. She on the left is Justice, carrying her scales, and she on the right is Truth, with her mirror, and wound about her other arm, a snake, symbol of Wisdom. (For more allegorical statues of Justice, see this page, and for statues of Truth, see this page.) The sculptor was Joseph Rose the Elder, who has one other large monument to his name, and with others in his family, was a maker of ornamental plasterwork. More details on the Ladbroke monument on this page.

Richard Ladbroke, d.1730: monument, reclining effigy, angel, and statue of Truth.

We take them in date order:

Mid and Late Victorian vertical panels: Hackblock and Blomfield.

Mid and Late Victorian vertical panels: Hackblock and Blomfield.

Ancient fittings are few, with most of the furnishings being 19th Century:

World War I memorial, ancient helmets, pulpit and part of the reredos.

The Church has an extensive burial ground behind and beside it, well cared for, and containing a range of the usual crosses, headstones and tablets, many with low relief carving of pots, flowers &co. There are a fair number of ‘eared’ tablets as shown here.

Waterlow monuments, late 19th Century, and typical eared headstone, 1840s.

The outstanding monument, bigger than all the rest and with sculptured angels, is that to Walter Blanford Waterlow, d.1891, and his wife Rebecca, d.1869. The monument is a great block faced in white stone, with panels on each long side commemorating husband and wife with a little shield held by two angels carved in high relief (see picture above right). On the short front towards the path is a relief carving of the Good Samaritan, now quite worn but still good. Up on top of all this is a sarcophagus, with a full sized seated angel at each end, slender and nicely draped. Really good work, though in its exposed position, rather doubtful if much of the sculpture will see out another century.

At a little distance, we may note a large Gothic panel above the entrance to a crypt, also to members of the Waterlow family; this includes a decent statue of a standing woman in Classical garb, hands spread out (picture above centre, you will need to click to enlarge).

Among those buried in the churchyard are the Victorian painters John Linnell and Samuel Palmer, the former a genre painter of rustic scenes, and the latter known for his romantic, other-worldly images of landscapes, either at night, or glowing with bright colours. The picture below is of the Samuel Palmer's monument, of the type known as a raised ledger.

Samuel Palmer's grave (picture by Mary Lambell).

Samuel Palmer's grave (picture by Mary Lambell).

With many thanks to the Church authorities for permission to show pictures from inside the St Mary's: their website is at http://www.stmaryreigate.org/our-buildings/. And thanks to Mary Lambell for the information she provided; she is the writer of the informative guide to St Mary Reigate.

Richard Ladbroke monument // Sculpture in some towns in England // Introduction to church monuments

Visits to this page from 19 Mar 2016: 11,354