From the south west corner of Parliament Square leads Broad Sanctuary, with the length of Westminster Abbey to the south, the Supreme Court on the north, and from here we can make a small walk, through Dean’s Yard in the Abbey precinct, and along quiet, ecclesiastical Tufton Street, see the strange former church of St John’s Smith Square, and its former graveyard, before returning along Great Smith Street, seeing a variety of architectural sculpture along the way – nothing too spectacular, but a number of individual pieces which together make up a goodly collection.

We start at the south-west corner of Parliament Square then – the various statuary in Parliament Square itself is described on a separate page – with Westminster Abbey to our south. Up above the grand main entrance in the north transept are pairs of figures – ten pairs in all – and the door itself has the expected line-up of smaller saintly figures in niches. What dates are we looking at? Unlike the ancient interior, the north front and north side of the nave were restored by Wren, and then later by the Victorian architects George Gilbert Scott and then by Pearson. The statues have the look of the 1860s and 1870s or thereabouts: one is signed ‘RJA’. They are well made, but rather high up to view properly, and are an inconsistent bunch: kings and queens with orbs and sceptres, shaven monks and clerics with Bibles and staffs, mitred Bishops carrying crosses, a pair of male angels. Their clothes too are in a variety of styles, Gothic, period costume, and for one of the angels, medieval Classical. However they match in their size, colour, standing poses mostly in pairs, and that each pair is within a double arch. The series continues along the north side of the nave with single figures in niches. Some, if not all of these figures are reproduced from monuments inside the Abbey – for example the Queen Eleanor from the Eleanor Crosses is conspicuous. Above the North Door, seated in a quatrefoil, sits St Peter with his keys, for the Abbey is also the Collegiate Church of St Peter. Again looking from the 1870s, or at least recut then.

Opposite, to the north of Broad Sanctuary, on the corner with Parliament Square, is the Supreme Court, built as the Middlesex Guildhall, and the sculpture is noted on the Parliament Square page. The side to Broad Sanctuary has a series of sculptures of pairs of busty angels. These divine creatures are by the sculptor H.C. Fehr, one of the ‘New Sculptors’ who were trained in the French manner and carved naturalistic figures with art nouveau faces.

Hawksmoor's West Front and carving by Henry Cheere

We proceed along Broad Sanctuary, to where it broadens out into the space by the West Front of Westminster Abbey, erected to the designs of the architect Nicholas Hawksmoor, the greatest follower of Christopher Wren. It was put up in the 1720s, and the sculptural decoration high up on the two towers, dating from 1734-44, is known to be by the sculptor Sir Henry Cheere. The principal decoration is above the clock faces all the way round, where there is highly undercut herbaceous carving, and winged, bearded heads, with festoons of flowers underneath. The designs and those festoons in the manner of church monuments are convincingly of the early 18th Century, so this would be the work of Cheere.

West Front sculpture by Tim Crawley, John Roberts, Neil Simmons, Andrew Tanser.

West Front sculpture by Tim Crawley, John Roberts, Neil Simmons, Andrew Tanser.

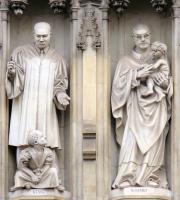

At the base of the West Front is the traditional entrance but today’s customary exit from Westminster Abbey, and the niches above it have been populated with small modern statues of latter-day Christian martyrs; a most successful ensemble. From left to right we have Maximilian Kolbe of Poland, Manche Masemola of South Africa, Janani Luwum of Uganda, Elizabeth, Grand Duchess of Russia, the American Martin Luther King Jr, Archbishop Oscar Romero of El Salvador, the German Lutherian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Esther John of Pakistan, Lucian Tapiedi of Papua New Guinea, and Wang Zhiming of China. At first glance, they are at one with the rest of the building, in pale limestone, standing and robed. But anything more than the merest glance shows their modernity if only by the lively un-Gothic poses of body and hand, most especially Kolbe and King, their many nationalities, and that a couple are wearing glasses. Like the older statues we have seen, the drapery is good but varied – thus Esther John tends to the formally Classical, Bonhoeffer has the crinkled and bulky sleeves characteristic of the 16th-17th Centuries, Romero and Luwum have careful Renaissance drapery with the emphasis on the restless edgings of the fabric, and King a modern, knee-length robe over a collar and tie. None have Gothic drapes. Of the portraits, the most characterful, for me at least, are Kolbe, Masemola and King.

Westminster Abbey West Front modern sculpture (names above, or click to enlarge).

The statues were put in place in 1998, and the sculptors were:

Below, to left and right of the entrance, are four more conventional modern allegorical female statues of Mercy, Peace, Truth and Justice. Mercy bears a chalice, Peace the usual leafy branch, Truth has a lamp, and Justice, unusually, has not her scales but a staff with a dove on top. The drapery is good, as are the long Gothic hands, but the faces are cold and hard. At least one of these four, and likely all of them, is by Tim Crawley again.

We might mention one of the buildings which used to front onto Broad Sanctuary, which was the Royal Aquarium, opened in 1876. The building was designed by a certain Alfred Bedborough. Despite the name, from the first, the Royal Aquarium showed other things as well as fishes – a fine art exhibition, headed up by Millais, music hall, winter gardens, skating rink and at the rear, the Aquarium Theatre, later the Imperial Theatre.

The Royal Aquarium building was itself rather splendid, as shown by the picture: red brick with a 600ft central hall with a glasshouse roof, and tall pointed spires upon open arched towers. The picture shows carved festoons at the end to Broad Sanctuary, rooftop ornaments, and just visible, statues on top of the central pediments on the long side of the building, and seemingly some sculptural groups within the pediments themselves. By the 1890s the fishes were not considered the main attraction, and one guide book noted that the ‘popular place of amusement belies its name, for it has but a beggarly show of fish’. By Edwardian times, these other amusements were failing to amuse too, and the Royal Aquarium was pulled down in 1902; the theatre lasted a little longer, till 1907, and then that was demolished too. The Methodist Central Hall was built on the site, and completed in 1912 – see bottom of page.

Royal Aquarium, on site of Methodist Central Hall.

In the centre of the triangular space that is the Sanctuary, acting as a roundabout for the coaches delivering tourists, is the memorial to the Westminster School Boys who went on to become soldiers ‘who died in the Russian [Crimean] and Indian wars, A.D.1854-59’. It consists of a tall red granite column, with four small carved lions around the base in limestone, and a Corinthian capital on which is a shrine-like topping of more limestone with four seated figures, and a summit statue of St George. The sculpture has been rather derided, I think on the basis of the feeble little lions, and the stiff pose of St George, who stands with his arm up, holding his downward pointing sword behind his back, the small and today headless dragon posed heraldically between his legs. The four seated statues below are much better, as indeed is the Victorian Gothic structure within which they sit. We have Edward the Confessor, with forked beard and crown; Queen Elizabeth with vast ruff, orb and sceptre, a rather thin King Henry III, and a youthful Queen Victoria. They are worn and a bit damaged in the arms and hands. The less good St George is by the sculptor J.R. Clayton, and the other and more significant and consistently excellent sculptor of the monument, John Birnie Philip, was responsible for the four monarchs. The architect of the Westminster Boys monument was the eminent George Gilbert Scott.

George Gilbert Scott's Sanctuary building and Westminster Scholars monument, sculpture by J.R. Clayton and J. Birnie Philip.

The block on the south side at right angles to the West Front of Westminster Abbey includes the entrance to Dean’s Yard, but before going through it, we pause to look at the building itself. This block, no. 4 The Sanctuary, is also to the design of George Gilbert Scott, dates from 1853, and is a superior thing. Above the Gothic gate is a gatehouse with octagonal towers, battlemented at the top, and Gothic windows. The two wings are asymmetrical but harmoniously balanced and proportioned so that this is hardly noticeable at first glance, a tribute to the understated skill of Gilbert Scott’s design. To the left, towards the Abbey, is more ornate Gothic, with pointed entrances and buttresses and steeply roofed dormers above the battlements of the fourth floor. Little balconies stick out with tracery cut in the stonework. The right hand side is somewhat plainer, retaining the Gothic windows but to a flatter, simpler design. At the top are stepped gables rather than dormers, and there is a protruding turret with windows all round as a feature at the end corner to Great Smith Street. The sculpture is relatively minor, but includes a little saint or two at that corner, heraldic angels, and above the central gate, niches with two standing figures of crowned kings.

Gilbert Scott's no.4, the Sanctuary, and sculptural decoration.

Through the gate now and into Dean’s Yard, which is a surviving bit of the medieval Abbey precincts. The sound of the busy street dies away after just a few paces. The reason to enter Dean’s Yard is the ambience, and above all the view from the further, south side, of the other side of Westminster Abbey, with its two layers of flying buttresses, most impressive, far more so than the familiar north facing side towards the street. Also, from the west side, the upper part of the Victoria Tower of the Houses of Parliament can be seen - a picture of which, caught in the evening light, is at the top of this page, far right; and from the south-east corner, looking north west, the top of the dome of Methodist Central Hall, which we will come back to at the end of the walk.

Dean's Yard: view of Westminster Abbey, and sculpture in the precinct.

There are a couple of bits of sculpture too. On the building occupying the south side of Dean’s Yard, which is one side of Church House by the architect Norman Baker – is a large statue in a niche of ‘the Prophet, the Foreseer, of the Deliberative Assembly of the Church of England’, by the prolific and excellent 20th Century sculptor Charles Wheeler. The Art Deco figure is a stylised muscular male, seated, with Roman hairstyle and robes, holding in front of him an open book, with between his knees a small angel - see picture above.

Above a window on the west side, part of the Westminster Abbey Choir School, is a charming pair of kneeling angels with musical instruments; winged cherub head corbels are below. Late Victorian or Edwardian. On the north side, a doorway with two corbel half-angels, holding shields, much decayed; again, see pictures above. (If you like angels, lots more on this page, and for cherub heads, see this page.)

Turning back for one last look at Westminster Abbey, the gate on the south side takes us out into Tufton Street.

St Edward's House, and statue of the saint.

St Edward's House, and statue of the saint.

Tufton Street is a narrow way going south towards Horseferry Road and the former church of St John Smith Square, which we are going to see. But Tufton Street itself has some modest architectural sculpture. Walk on the right hand side to see the buildings on the left. The first block, numbered 22 Great College Street rather than a Tufton Street address, has a mildly Tudor Gothic doorway, above which is a niche with a typical small ecclesiastical statue. The building is St Edward’s House, and the figure is St Edward. He is made in white limestone, a little decayed, wearing a crown above his full-bearded face, sceptre crooked in one arm, the other holding a ring. Simply robed. Made with typical Victorian competence, but the face a bit too kindly and lacking any hard edge to the features. Beneath, a pair of half-figure angels holding shields, simply carved in stone.

Wippell & Co, with wooden carving, and view back along Tufton Street.

A couple of doors down, at no. 11 Tufton Street is J. Wippell & Company Ltd, ecclesiastical outfitters, with original Victorian wooden shop front, and two wooden panes with carved high relief figures in shallow Romanesque niches. One figure is a statuesque Roman female, carrying a feather, which perhaps is a quill pen. The other is a Roman man, carrying the capital of a pillar and the tools of a sculptor; perhaps they represent Literature and the Arts.

The entrance to Number 7, Faith House, has an ornate sign (see picture above right), and then on the corner of Great Peter Street is the one-time Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Places, dating from 1907. Above the principal doorway is a frieze, a bit too small to appreciate properly without visual aid, showing the work of the Society: a tall ship with a gospel-preaching priest standing at the front, faced by a rocky island where stand a little group of five natives in front of a palm tree. Charming. The ship is a good piece - if you like ship sculpture see this page. At the very corner of the building, in another niche, is another standing figure of a saint, a better piece than the St Edward we saw before, with serious face, strength to the arms and hands, and swirling drapes. In one hand he holds a book, the other, an upturned sword.

Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Places, 1907.

On the opposite corner is the Mary Sumner House, with a cartouche bearing a fine winged cherub head and nicely carved festoons of fruit and flowers.

Carrying on and then turning left, or turning left and then right, takes us through several ancient streets, charming in scale and some with 17th Century doorways – and one with the house where T.E. Lawrence lived among various other luminaries – to Smith Square. The approaching streets give similar views at the end of the former church of St John’s Smith Square, for it is square in plan, with Baroque towers at the four corners and two porticoes with pillars, and two flat-fronted sides with windows and pilasters. Thomas Archer was the architect, contemporary of Hawksmoor, and this church was one of the ’50 new churches’ intended to be put up from the 1710s, though in the end only a dozen or so were erected. St John Smith Square was the most expensive, costing £40,000, and was erected in 1714-28. The interior is long gone – a fire in the 1740s, refurbishment in 1824, and bombed in World War II – and it is now a musical venue. I only know of one monument which used to be within the Church, a tablet with medallion portrait to John Jennings, Archdeacon of Westminster, d.1883. There had also been 16th Century stained glass, from a church in Rouen.

St John Smith Square, designed by Thomas Archer.

The Baroque exterior survives. The building began to sink as it was being built, and the four stone towers apparently were put there so that the whole might sink equally. It was much condemned – Charles Dickens said it was ‘a very hideous church, with four towers at the four corners, generally resembling some petrified monster, frightful and gigantic, on its back with its legs in the air.’ Another commentator thought it looked like an elephant lying on its back, and one story was that Archer had asked Queen Anne what the Church should look like, and she kicked her footstool upside down and said ‘Like that’. Benjamin Disraeli was more measured, calling it ‘a church of vast proportions, and built of hewn stone in that stately, not to say ponderous style, which Vanbrugh introduced’ – Vanbrugh being Archer’s master.

We have no sculpture to see, bar the carving on the pillars etc, but the cylindrical towers, each with a cupola surmounted with a pineapple on top (Archer originally planned pinnacles), are worth seeing. For lots more London churches and their sculptural contents, start from this page.

T.E. Lawrence's house off Smith Square.

T.E. Lawrence's house off Smith Square.

Continuing southwards along Dean Bradley Street takes us to Horseferry Road, and on the opposite side of this is the former burial ground of the Church.

The burial ground of St John Smith Square, now called St John’s Gardens, was closed to burials in 1853, and converted to a public gardens in 1885. A few headstones are against the walls to west and east, but are quite destroyed by spalling and what little text remains is generally unreadable, with the exception of the larger headstone to Admiral Cornthwaite Ommanney, d.1801 and relatives – a distinguished naval family which included other admirals and explorers. One raised ledger surrounded by bars survives, and one great tomb chest of granite to Christopher Cass, d.1734, Master Mason to his Maj[esty’s] Ordnance. Cass had made repairs to St John Smith Square, and worked on others of the 50 New Churches, as well as working on grand residences such as Blenheim Palace and Chevening. The inscription on the tomb is on the front panel, the top has mouldings and a curved lid, and the sides have recessed arches. Unusual, and also really very early for an English granite tomb.

St John's Gardens, former burial ground, and tomb of Christopher Cass, master mason, d.1734.

There also survives a central water feature, with a fountain consisting of a bowl carved as a petalled flower resting on a fluted pillar, above which three Classical dolphins – fishes really – pour water from their mouths. This would date from the 1885 opening I would think.

There are a few modern sculptural plaques on the surrounding buildings. Firstly, to the south, there are four panels, set vertically, so the highest is difficult to see, and obscured by trees to boot. They show male nudes in an attitude of action. One, with gearwheels, looks to be Engineering, another is in front of a group of books and scrolls so conceivably Literature, though his running pose militates against that; a third, with car, sextant and bridge is Transport, and the fourth, with hand to ear while he is shouting, and with a telephone, is Communication. Stylised work in a 1930s mode.

The second group of panels face outwards from the square back onto Horseferry Road. They include a pair of hands and a sunburst, what looks like a Primrose League badge, crowned, with a book; and a crowned heraldic eagle with one claw on a sceptre. Other lesser plaques may be seen on buildings in the surrounding streets, notably on the Westminster Hospital Nurses Home.

Sculpture in and around St John's Gardens.

We return towards Parliament Square along Marsham Street, just to the west of Tufton Street. The start is unprepossessing for those in search of sculpture – a massive modern Government building of three blocks, opposite which is one red brick effort with a ship’s prow protruding from above a Roman arch.

Further north, crossing over Great Peter Street, the road becomes Great Smith Street, with more to see. First we have the former Public Baths, with separate entrances for men and women. Above those is a projecting bay window, with three small friezes showing carved swimmers in high relief, by the sculptor Henry Poole. Each panel shows a pair of nude male swimmers, diving, swimming and leaving the water. Alongside this building is the former Free Public Library, a ‘very useful institution, the benefits of which are highly appreciated by a large number of that particular class of the inhabitants for whose service it was specially erected. The library, dated 1893, by the architect Francis J.R. Smith, is in Jacobean style, made of red brick and stone. Medallion portraits carved in relief show Spenser, Shakespeare and Chaucer on the left, and to the right, Drydon, Milton and Tennyson’. They are quoted by British Listed Buildings as being by Henry Poole & Son, but I think mean the later Henry Poole again, as Henry Poole and Son was the firm of his grandfather, which was located at least for a time at 11 Great Smith Street.

Library, Great Smith Street, 1893, with portrait medallions.

Opposite the Baths and Library is the sombre dark brick, flint and stone frontage of Church House, of which we saw the reverse side in Dean’s Yard. Two shields of arms and a large Royal Coat of Arms in stone adorn the building.

Terra Cotta details, Park House (Education Dept), Great Peter Street.

Next along back on the left hand side is a significant building, now the frontage for the Education Department. The red brick and pinkish terracotta building abounds with Arts and Crafts decorative features, including curly cartouches, S-shaped corbels, and terminals. The building, called Park House, dates from 1904. Just along, by the corner of Abbey Orchard Street (a reference of course to the site of the orchard which supplied Westminster Abbey) is another terra cotta building. The corner door gives its name as Orchard House, in At Nouveau text, with low relief mouldings of apple trees. Beneath this are a pair of female heads with wavy hair, as corbels. Round the corner in Abbey Orchard Street are a pair of peacocks carved in low relief above a window, with clustered leaves above. Again, beneath are a pair of female heads as corbels, with further foliage. All this, and perhaps the designs of the rest of the more minor decoration, are the delicate, formal and perfectly stylised work of the 1900s by the Arts and Crafts designer and ceramicist W. J. Neatby. 1898 is the date.

More terra cotta - W.J. Neatby's decorations for Orchard House.

Keeping to that side of the road, the left hand as we continue north, we can note up on the wall of a 1900 stone building to the right, an almond-shaped bronze panel in a square stone surround carved with tracery, with the inscription 3rd Anne, November 3rd 1704 – a reference to Queen Anne setting up ‘Queen Anne Bounty’, giving an originally Papal tax to poor clergy via the ‘Church First Fruits Board’. The bronze shows a seated Queen Anne, under a canopy of knotted fabric, with a crowd of admiring clergy crouched at her feet.

And then we are back at the corner of The Sanctuary, with Parliament Square where we started just to the right.

Queen Anne Bounty panel, Great Smith Street.

The final building on the walk, with architectural sculpture, is the Methodist Central Hall. We saw the dome when in Dean’s Yard. Lanchester and Rickards were the architects of this magnificent and vast Edwardian Renaissance style building. As noted above, it was built on the site of the Royal Aquarium.

Westminster Methodist Central Hall.

The Methodist Wesleyan Central Hall was put up in 1907-12, containing a huge hall seating 2500 people. The dome is one of the largest – at the time it was built, only St Paul’s Cathedral and the British Museum Reading Room domes exceeded it in size – and from the ground to the top of the finial at the very summit is 212 ft. The sculptural decoration company H.H. Martyn and Co of Cheltenham made the interior panelling and other woodwork, and J. Whitehead & Sons of London were responsible for the marble work. Happily, we have external sculpture to see, including two large figures over the main window. They are spandrel girls, for they fill the roughly triangular spaces (spandrels) between the arched window and the rectangular surround. Each leans forward towards the centre, holding a festoon of drapery filled with fruit and flowers, the end of which hangs down almost to Their knees. The figures are almost identical in reversed pose, but the details – hair, drapery – is different. Very large, very fair of face and slender of body. Henry Poole was the sculptor – we have already met him at the Public Baths noted above – and these are among his largest works, I think, exceeded only by his massive groups for Cardiff City Hall. I would think that Poole also carved the ornaments above the pillars to the sides, and around the corner: we see bull’s heads, eagles, lion heads, and one beautiful female head. Poole certainly modelled the lead trophies around the base of the dome. The vases however were by the sculptor H.C. Fehr, another New Sculptor known for his ideal female nudes and his war memorials - we met him at the very beginning of the walk, just along the road in his sculpted angels for the Supreme Court.

Henry Poole's caryatids, Methodist Central Hall.

East to Parliament Square sculpture // West to Victoria Station sculpture

London sculpture // Architects

Visits to this page from 21 Apr 2017: 12,600