Crouch End/Hornsey sculpture by Arthur Ayres

Hornsey Gas Company with panels carved by Arthur Ayres.

The fine series of panels on the one-time Hornsey Gas Company building, in Crouch End, London, was made by the modern sculptor Arthur Ayres – together with a panel on the neighbouring Town Hall and a brick figure opposite, they constitute an ensemble of works by this artist.

The building itself is a rather poor Art Deco thin, brick and very large windows, whose existence we can forgive because of the sculptural decoration. It was put up in the mid-1930s and one of the sculptural panels is dated August 1937. The Hornsey Gas Company was a 19th Century company, instigated to supply gas to the local area, which eventually was nationalised shortly after World War II.

Agriculture and Architecture panels by Arthur Ayres, Hornsey Gas Showroom.

There are eight panels in all, four facing inwards towards the nondescript green area in front of Hornsey Town Hall one angled at the corner above the entrance, and three to The Broadway, which is Hornsey's High Street. They mostly illustrate the uses of gas, and I have suggested the likely titles for some of them, but the first panel, closest to the Town Hall, is an allegorical group of Agriculture. A girl is seated, legs splayed so that her dress can support a sheaf of corn; in one hand she holds a small flower which she contemplates. The male figure is behind and has his back to us, with his head in profile, and holds a scythe rather menacingly above the girl’s head; in front of his seat rests the girl’s sickle. In the upper corners fly a pair of birds, doves seemingly. The composition is good, filling the space effectively and with a contrast between the two figures: she is young and beautiful of face, he s square headed and grim; both have a distortion to pose and body often found in sculpture of this period. (For more sculpture of Agriculture, see this page.)

The second relief panel is of three men gathered round an architectural drawing, one seated, and two standing, each with an architectural implement; this is the one with the date, and a clock shows the time at half past twelve.

The third panel depicts Gas for domestic heating. It shows a family group, rather similar to the couple in the Agricultural panel, but her with a naked infant, cheek pressed against his mother’s breast. She looks down towards a symbolic gas flame, tilting her lap to bring the infant closer to the warmth; the father sits gazing in the opposite direction.

Our next panel, Gas for water heating shows the girl on her own, with the gas flame above her hand, warming water pouring from a pipe; at first glance she appears nude, but is wearing a figure-hugging garment, as she has visible sleeves and hem to her long dress. This is a rather excellent Art Deco pose, one arm up and across her head, the other outstretched, the angles of the hands stilted and clever; equally her legs and feet give a mannerist feel to the carving.

The corner panel, number five in the sequence, Gas for lighting, shows a masculine figure, youthful this time, holding a flaming torch and a palm leaf, and half kneeling on three steps.

Next, round the corner facing onto the High Street, we have Gas for cooking with the girl again, gas flame above her hand once more, and with a drape across both arms providing a vessel for her fruit and vegetables: we see a pear, lemon, pineapple perhaps, two leeks and a bunch of grapes, and orange, apple perhaps, and seemingly a gherkin. I think this must be gas for cooking. In this panel the girl is semi-nude, wearing a diaphanous skirt, but with upper body bare. The lines of her figure are most graceful.

Panel number seven shows two mine workers, kneeling and sitting, one using his pickaxe, the other with spade and davey lamp, which would have used oil rather than gas. Presumably they are coal miners, coal being the starting point for synthesis gas.

The final panel, The Gas burner is a scene inside a Chemistry lab, with two scientists using a gas burner to heat a retort to distil some liquid which they collect via a funnel; at the front are test tubes for the different fractions of distillate, and one of the scientists holds up one of these test tubes to look at it to examine the liquid within.

Hornsey Town Hall, 1934-5, by Reginald Uren, panel by Arthur Ayres.

Hornsey Town Hall fronts onto the open space, with its tall, square tower of brown brick: it looks rather like a church, and there are various rather similar looking churches in north west London, along the Metropolitan line and built at similar date. The Town Hall was opened in 1935, and in its day was a celebrated building by the then very young architect Reginald Uren of New Zealand, Nordic influenced. All rather spare and unornamented, save for the entrance beneath the tower, which has a frieze above the door again by Arthur Ayres, and ironwork. The panel has a heraldic shield: the arms of Hornsey Metropolitan Borough at the time (later local government reorganisation saw it amalgamated with Wood Green and Tottenham to become the London Borough of Haringey). To the left and right are hunting scenes with hounds, pulling down a stag on the left, and with a fierce boar at bay on the right: perhaps in reference to Hornsey’s motto, ‘The better prepared, the stronger’. Interesting in showing examples of the sculptor Ayre’s technique with animals: the stag conventional, the hounds more characterful, the boar the best of the group, with its fierce little eye and defiant aspect.

A final example of Ayre’s work is on the building to the left hand side of the Town Hall as we look at it, a brick figure, a nude male, high up on the wall, with thunderbolts and stars; he represent Electricity, for this building was the Electricity Board Office, put up in 1938-39, with Uren as again one of the architects, with Slater and Moberly.

There is a little more sculpture to see in the vicinity. One more modern piece, round the corner by the library by Hatherley Gardens, is in the fountain: an odd, attenuated female nude by Thomas Huxley-Jones.

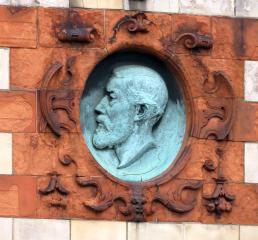

Hornsey Clock Tower, and portrait of H.R.Williams by Alfred Gilbert.

A little way along The Broadway is an open space forming the junction with Coleridge Road and Crouch End Hill, wherein is the Hornsey Clock Tower, a nice Victorian thing in several stages. The base is of rough hewn limestone blocks, and has upon it a typical Victorian drinking fountain, a modest granite thing. The second stage, of similar height to the first, perhaps 8 ft high, is of banded red and pink terracotta, and contains a high relief profile portrait sculpture in an oval, of Henry Reader Williams: it is a minor work by the important sculptor Alfred Gilbert. Williams was a local worthy, who among other things pushed through the establishment of Priory Park nearby. Next, a tall stage of dark red brick with minor pink terra cotta banding: four arched-top window frames – the windows themselves are narrow slits within – a central slit window, and the large clock face on each side, surrounded with a frame of terra cotta and brick. The corners of this part of the tower protrude somewhat, and are capped as part of the fourth stage with short corner turrets. They, and the large central, octagonal turret, which has round windows, are each capped with a dome with a point on top: the central one has an elaborate windvane. The whole of this fourth stage is of beige-pink terracotta. The Clock Tower dates from 1895, and the architect was a certain F. G. Knight. Another charming commemorative London clock tower, of later date than this one and smaller, is at Stepney Green - see this page.

We should also mention the historical remnant of Hornsey Parish Church. St Mary’s Hornsey was of ancient origin, and in the 1830s was felt to be too small for the local populace. The tower, dating from the 15the Century, was kept, and the rest pulled down, insult added to injury by building the new, larger church immediately adjacent. Revenge came when the interloper was closed in the 1880s, and pulled down in 1927, leaving the old tower to remain in isolation. There is a small surrounding churchyard, now a garden, with some of the tombstones surviving, though in the 1950s or thereabouts the Council thoughtfully flattened most of them. Most of what remains seems to date from the time of the later church. A note on the monuments formerly in the Church on this page.

Tower of St Mary, Hornsey, 15th Century, and gravestones and tomb chests in the churchyard.

This page was originally part of a 'sculpture of the month' series, for Feb. 2016. Although the older pages in that series have been absorbed within the site, if you would wish to follow the original monthly series, then jump to the next month (March 2016) or the previous month (Jan. 2016). To continue, go to the bottom of each page where a paragraph like this one allows you to continue to follow the monthly links.