St Mary's Church, Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire - Monuments

The chief artistic interest of St Mary Hemel Hempstead lies doubtless in its architectural features: the extensive Norman carving, and the splendid medieval spire, rather than the monuments within. Nevertheless, they form a decent collection of 15 or so panels dating from the late 17th Century through to the mid-20th Century, and one really good ancient brass.

The Norman Church of St Mary, Hemel Hempstead.

The briefest note on the Church building itself first, as this is covered so extensively in so many places. It is sited in the old town, on the High Street, which is a pleasant surprise in its preservation to those who have only visited the utilitarian and rather hideous New Town (late 1940s and thereafter) near to the railway station. The tall leaded spire, one of the tallest Parish churches at 200ft apparently, is octagonal, and maybe dates from the 13th Century, according to the Royal Commission on Historic Monuments. It rises somewhat abruptly from the square tower without any connecting feature or balustrade, and that tower is centrally placed, for the church is cruciform. It is essentially a Norman building, built 1140-1180 or thereabouts, built like a Cathedral starting from the chancel, then the transepts, and only after that constructing the Nave and contemporary aisles. In the 14th and 15th Centuries the porches were added, and there was enlargement of some windows and doorways. Finally, we have the two Vestries added filling out the angle between north transept and the Chancel in the 19th Century. The building is flint faced with pale stone around the windows, and we see both original Norman windows higher up on the nave at clerestory level - Pevsner says that a contemporary Norman clerestory like this is a rarity - and the Gothic enlargements elsewhere (mostly Perpendicular but Decorated in the south wall of the Chancel). One splendid Norman doorway survives, of three orders.

The Chancel, and aisle with monuments.

It is not just the spire which is so tall - the building as a whole is of considerable size, and the impact inside is of the loftiness of the nave, and the massive solidity of the piers to the Norman arches, with a further great arch to the chancel. Our monuments are mostly ranked along the aisle walls.

Monuments

Richard Combe, d.1692, 'The Eldest son of Sir Richard Combe Knight// The Father's First // The Family's Last'. The pale marble inscribed panel is flanked by black-shafted pillars with white capitals and bases, supporting a shelf on which rests a shield of arms surrounded by leafy mantling. Outside and behind the pillars are short feathery scrolls. A shelf at the base is help up on blocky supports of black marble, with a short apron between in a grey, brecciated marble: central to this is a dark panel to Dame Anne Combe, d.1658? with a heavily carved shield of arms below; three others are to the sides and under it - these are coffin plates, which would once have been on the coffins of members of the family buried in the family crypt - there are passing notes of people reading such things in Thomas Hardy's A Pair of Blue Eyes.

Seth Partridge, d.1686, son also Seth Partridge, d.1703, and eponymous grandson Seth Partridge, d.1748, and Thomas Partridge, d.1755? Worn inscription within what would seem to be a later surround, anything from 1820s up to the mid 20th Century I would think, with upper and lower shelf and small supports.

Thomas Salter monument.

Thomas Salter, with a faded inscription which I could not well read in the light available. On top is a coat of arms with much mantling, festoons of flowers to each side, and rather shell-like urns with flamboyant flames emitting from them. Most striking. At the base, shelf, and below that, crossed branches and a terminus of a pair of winged cherub heads. (If you like cherubs, see this page).

Windmill Crompton, d.1771, and wife Elizabeth Crompton, d.1770 - if I read the dates right. He was a linen draper who became bankrupt, and was the father of another Elizabeth Crompton, a renowned beauty who married the Earl of Marchmont and whose monument is noted below. Another replacement surround to the inscription, as per the Partridge inscription noted above.

Hugh, Earl of Marchmont and Elizabeth, Countess.

Hugh, Earl of Marchmont, d.1794, and Elizabeth, Countess of Marchmont, d.1797. For such an illustrious pair, the monument is again rather modest, being another panel with dull surround, upper entablature and moulded shelf, lower shelf and brackets. It is at least in different coloured marbles, dulled by dirt and age, and I would think guess that this piece formed the model for the replacement surrounds to the Partridge and Crompton monuments.

The Revd. William Bingham, d.1819, Rector of the Church, thereafter Archdeacon of London, and previously vicar of Great Gaddesden, also in Hertfordshire, where he was buried. The inscription is on an oval within a rectangular frame, the corners (spandrels) with delicate triangular patterning. The upper and lower shelf are moulded and there are three small brackets.

Margaret Collett, d.1826. With a funereal urn in high relief, semi-draped, on top, and a shaped black backing. The urn, of a broad, somewhat oriental style, and the drapery, is cleanly cut, and this is a minor work by the sculptor Ternouth of Pimlico, whose most known work, not that many would know it was by him, is one of the panels at the base of Nelson's Column. See picture below left.

Jacob Theophilus Mountain, d.1827, midshipman on the ship North Star, drowned off the coast of Africa aged 15. White on black panel, with shield of arms and curved outwards shelf at the base, not that usual. I half imagined to see a mason's signature, but if so it was too worn for me to read.

White-on-black panels: Margaret Collett and Frances Mountain.

The Hon. Henry Watson, d.1833, white on black casket tomb with ball-feet, on a black backing cut from several pieces. Signed by a Hertfordshire stonemason, Joseph Pigg of Watford - he had premises in the High Street, and was active in the 1830s and 1840s, but is quite obscure.

Frances Mingay Mountain, d.1837, wife of the Vicar noted above, white on black panel carved as an open book, which was a style moderately favoured as one of a number of variants on a simple plaque without involving too much carving. Signed on the small central supporting bracket by the Patent Works, Westminster, a company which is responsible for a number of white on black panels in different variations on the Classical. See picture above right.

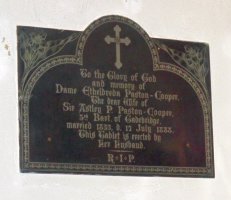

Sir Astley Paston Cooper, Baronet, d.1841, and wife Lady Anne Cooper, d.1827, with the curious note that she was 'pious without enthusiasm', their adopted daughter Sarah Parmenter, d.1814, and, added later, Catherine, d, 1870, second wife - see picture at top of page, which you will need to click to enlarge. Among the Classical panels in marble, we have this pale stone Gothic monument, styled as a blind window with tall crocketed spires, and a painted shield of arms and minor carved decoration below. By Samuel Manning and John Bacon, a significant partnership who produced various tablets and more complex monuments – though while the Victorian period produced a revival of Gothic panels, Bacon and Manning's work which I have seen elsewhere is generally Classical (See this page for a note on Bacon.)

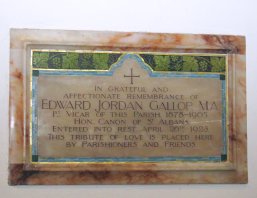

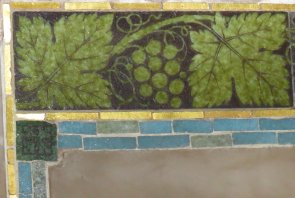

Revd. Edward Jordan Gallop, d.1923, first Vicar of the Parish and afterwards Hon.Canon of St Albans. An Arts and Crafts panel in characteristic glowing colours: pinky-brown alabaster frame, central pearly lightert marble or alabaster, bordered with thin blue and gold mosaic, with small green tiles with a repeating vine design = picture above. Super.

James Steptoe, d.1928. Plain panel with chunky marble frame: a few years later, and the frame would not have been included.

Lovel Smeathman, d.1932, churchwarden, panel with red lettering and coloured alabaster surround, and upper shelf – quite ostentatious for that generally abstemious period.

Archibald Francis Robson, Vicar to 1944, wooden plaque.

Richard Combe, d.1692, and coffin plates.

Ancient Brass:

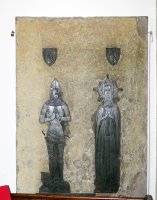

Robert Albyn and his wife, Margaret, 14th Century.

Robert Albyn and his wife, Margaret Albyn. A really splendid piece of the 14th Century. We have the husband and wife, standing, facing the viewer directly, hands raised in prayer, as is normal, and each resting their feet on a heraldic animal, which is more usual for sculpture - his is a lion, hers a dog. This is because they are lying down, and she has a cushion under her head, ornamented and multi-tasselled. Above each is their shield of arms, and below his feet are the remains of the two line inscription - as ever, difficult to read, so Robert reads more as 'Robrd' and the Albyn has a small 'a' looking like a 'z'. He is in full plate mail, with conical helmet with chain mail to cover the neck, nice gloves, sword and dagger attached to a double belt, and pointed, armadillo-flexible boots. She has some headpiece, and wears a long, open cloak over her long dress, belted at the waist to emphasise her figure. The cloak is held with a cord across the front and hanging down to tasselled ends. She wears the sleeves of her shirt over the lower palms of her hands. Excellent.

Modern Brasses and other metal plaques:

There are several of these, mostly to the Paston Cooper and Talbot families, and we may pick out:

Dame Elizabeth H. Cooper, d.1878, noting the East Window and Reredos were erected by her nine surviving children in 1880.

Dame Etheldreda Paston-Cooper, d.1888 - panel with raised centre to include a cross trefly, with inscribed flowers to the sides. A less usual design - see below.

George Frederick Paston Cooper, d.1895, with a stylised leafy repeating border, cross and insignia.

Samuel Seabrook, d.1919, choirmaster of the Church for 31 years. Black metal panel with small crosses.

Robert William Rolfe, d.1924, with repeating leaf border.

Also in the Church:

Capitals of the thick Norman pillars, with original carving of leaves, masklike faces, crude but disturbing, and a strange horse-like animal with oversized head; a sample is above right.

The Font, Norman in the massiveness of its single pillar support and base decorated with overlapping semicircles. The square top is characteristic of many Norman fonts too, but the figures are recent, or heavily recut, perhaps turn of the 19th Century or later.

Two piscinae, 14th and 15th Century = one is shown above left.

Amedieval chest, so satisfying to find in a church, typically once used for vestments or plate, of dark wood bound with strips of iron.

A medieval or earlier graffiti showing the armoured head of a knight; of historical rather than artistic interest.

Old chairs in honey-coloured to dark wood with twisted shafts, and some more curvy pieces of more recent date, and a church gong. The pulpit is also of wood.

Large painted Royal Arms.

A tall, painted dark board listing benefactors to the Church. There are separate boards for Thomas Warren, d.1796, who left a large bequest from which two free schools were established, and for Mary Fields, whose will is dated 1814 – along with bread and coals for the poor elderly of the parish and funding of the Sunday School mistress, she left money for the graves of her mother and niece to be upkept.

19th Century tiling with medieval designs, Mintons or similar.

Some panels of Victorian and later stained glass.

The Chancel Arch, which like so much here is Norman, has above it a painted Arts and Crafts Assumption, with the Virgin and angel as very fine, figures, and a rich gilt surround with potted plants and an incense burner, trees and city in the background behind a cloistered wall - see picture above. Designed by the estimable G.F. Bodley, dating from 1888.

First World War Memorial - a stone plaque listing the fallen, with flags to either side; a smaller plaque below is for WW2.

Hemel Hempstead Churchyard

The Churchyard has been mainly cleared, but the walls to it have been lined with many gravestones; unfortunately thus allowing the wind to flow freely has mean that they are decaying more rapidly than had they been left in situ, and many are placed one in front of the other, but some inscriptions and designs can still be appreciated.

It is a shame that the 18th Century stones at least are not better looked after, for they are a fair collection which should be preserved. Their characteristic thick structures and curly tops, with winged cherub heads and skulls and crossbones carved in high relief, are worth seeking out. The earliest of the latter I found was actually 17th Century, an unusual survival, and the first I could read the name on was to Jane Chapman, d.1705, still early, as well as ones whose date I could not decipher but may be similarly early, and several from towards the end of the century, which are more frequently found in churchyards I have visited.

From the 19th Century, there is a representative variety of headstones, with some minor decorative carving, Gothic arched or from Victorian times, Gothic blind window design, even the odd Romanesque arch with dogteeth designs doubtless inspired by the Cathedral, and various crosses, including 'keyhole' style slabs with a bulky, rounded head to the cross, and ones with cut outs.

Gravestones from against the wall, Hemel Hempstead churchyard.

St Mary's website, with good historical information, is at https://stmaryandstpaulhemel.org.uk/about-us/st-marys-history/#M01.