Monuments in St Alphage London Wall

Nothing survives of the wall monuments in the slight ruins of St Alphage London Wall, once Elsynge Spital chapel, in the City of London. However, pictures of some are preserved, and these are noted here, with a bit of background of the origin and grim fate of the Church.

St Alphage London Wall, sometimes called St Alphege, in the remains of Elsynge Spital, sometimes spelt Elsinge, survives as a small ruin on the street called London Wall, along with a chunk of the London Wall itself. While all the wall monuments are destroyed, we are fortunate that pictures of those extant before World War II were photographed, and published mostly in a book by Pierson Carter dated 1925. Carter’s book pictures 11 monuments:

Sir Rowland Hayward, d.1593, his two wives, and 16 children. The oldest and most interesting monument of the crop. It is a kneeler monument, but an unusual one. Kneeler monuments normally show husband and wife facing each other, but here, as we have two wives, we have Sir Rowland facing towards the viewer, and his wives facing him on each side (you will need to click on the picture above to see them properly). More unusually, the children would normally be ranged behind the parents, boys behind their father, girls behind their mother. Here, the distinction between the sexes is done by placing the boys in front of their respective mothers, the girls behind. They are numerous: three sons and five daughters to Johan [Tilsworth] Hayward, the first wife, and a further three sons and five daughters to Katherin [Smith] Hayward, his second wife. We can see that Johan [Joan] is the wife on the left as we view the monument (i.e. Sir Rowland’s right), by the number of little skulls held by the offspring who pre-deceased their parents. Also unusual is the way that the flocks of are is not in the usual line or strict pairs according to age, but more casually disposed. The monument is divided into three horizontal fields by Corinthian pillars, and above is an entablature, the painted arms of the three parents within circles with minor ornament of the type termed strapwork, and with memento mori obelisks at the corners. There is a deep base with scrolling and a further shield of arms, and all of this décor is fairly usual for monuments of this time: see the page on kneeler monuments. A good piece, and a sad loss.

Samuel Wright, d.1736, who was a serious benefactor [a rector, Thomas Wright, d.1700 was commemorated by a floor slab]. We see an interesting figure group above the inscription, a nursing mother with infant and two larger naked offspring, thus a depiction of Charity (monument to the left in the picture above, click to enlarge). Corinthian columns to the side support an open pediment, enclosing a winged cherub’s head, and with on top, some shield of arms and two remnants of what look like funereal urns to the sides. Coloured sketches of the monument show a steaky grey and purple backing and sides to the off-white inscribed panels, sculptural group and decorations; use of coloured marbles was common at this time.

The pike maker's monument.

John Edwards, d.1646, pike maker, and his wife Katherine Edwards, d.1698, set up by a son, William Edwards, also a pike maker, in 1676; an inscription to Bridget Shorter, d.1709, sister of Margret Edwards was added later. Written rather than carved text, with carved crossed banners [Triumph] and cannon and a cartouche at the top of the panel, hanging flowers down the sides, and roundels at the base.

The wire drawer's monument.

Benjamin Russell, d.1715, Wiredrawer of the parish, his wife Christian Russell, d.1724, son James Russell, d.1697/8 ?, William Molyneux, d.1722, who was ‘Mrs Russell’s Nephew, bred up in the Family’. Christian Russell left her considerable estate to charitable uses, including £100 to repairing the Church, alas, and more usefully, a further hundred pounds for the relief of poor Clergymen’s widows, and various other amounts. Tall panel with a curved shelf above, projecting sides on brackets, and under the shelf, a relief carving of a winged cherub head. Lots of winged cherub heads on this page.

Wright and Hayward monuments

There are also half a dozen of the simpler white-on-black panels typical of the early 19th Century, based on the common tomb-chest end design: the inscribed panel with flat or pointed lid on top, and standing on little feet. A variant, with upwardly outward slanting sides, is the casket end.

These first two examples have minor carving on top:

The Revd. John Roberson, d.1824. white-on-black casket end with a funereal urn carved in relief on top, picture above left.

Leonard Willshire, d.1840, and his wife Rachael Willshire, d.1836. The tomb chest has a high relief carving of a wilting tree (a fairly common emblem of death) over a partially shrouded pot - see above right, click to enlarge.

Also in the picture is the plain plaque to Peter Leonard, d.1845, and his wife Ann Leonard, d.1831.

Variants on the tomb chest end.

Samuel Buxton, d.1846, cut as tomb chest end, really very plain, picture above left.

Anna Margaret Kemp, d.1861, wife of the Revd. Kemp noted below. Variant on a tomb chest end on a shaped black backing composition, with heavy upper part enclosing a carved wreath and ribbons, curly sidepieces with foliage, and unusually, the feet linked by a more carefully carved festoon of flowers. Picture above right.

Elizabeth Lucy Perlam, d.1828, and Martha Roberson, d.1838, both wives of vicars of other churches. A traditional tomb chest end cut with pediment—like lid, plain acroteria (‘ears’), and the usual little feet, on a plain dark backing. The lower panel in the picture above.

The Revd. George Kemp, d.1878, Rector. A change from the usual tomb chest end or casket end shapes: thus the panel has curled sidepieces with carved anthemions at the bases, supporting a shelf with a low roughly pediment shaped block on top, carved in relief with a central shield of arms and scrolling. On a curvy shaped black backing. Upper panel in the picture above.

Previous monuments:

There are records of earlier monuments: the great topographical historian John Stow notes the defacement of 14th and 15th Century monuments there, to members of the Cheney and Frowike families among others, but does not say which monuments that he himself saw there at the end of the 17th Century (i.e. when working on his Survey of London published in 1698). John Strype, who updated and enlarged Stow’s great work in 1720, mentions the ‘very goodly monument’ to Sir Rowland Haward, and the piece to John Edwards also noted above, and around a dozen others from the 17th Century which are referred to as monuments or ‘flat stones’ which would likely be floor slabs, and so outside the scope of this website (and, incidently, may in some cases have survived as some floor slabs were moved to the City of London cemetery, Manor Park).

The Church building and ruins:

Building of Elynge Spital:

What we see today, clearly set out in informative City of London Corporation panels on the site, is the remains of the tower of the chapel of Elsynge Spital, founded in 1329, and taken over by St Alphage when they moved from their previous church down the road (ie along London Wall, on the other side). The founder, William Elsynge [William Elsing] was a mercer, and built the Hospital within the grounds of an old Augustinian nunnery, as described by John Stow, ‘for sustentation of 100 blind men, towardes the erection whereof, he gave his two houses in the parishes of St Alphage, and our blessed Lady in Aldermanbury neare Cripplegate. This house was after called a Priorie or Hospital of S. Mary the Virgin, founded in the yeare 1331 by W. Elsing for Canons regular: the which W. [i.e. William Elsing or Elsynge] became the first Prior there.’ Further donations were given by Elsynge’s son and grandson.

Danish connection of St Alphage:

Elsynge Priory was surrendered to Henry VIII in 1531, and Stow notes that part of the Hospital was made into a dwelling house, which was occupied by Sir John Williams, Master of the King’s Jewels, in 1541 when a great fire consumed it. The chapel of Elsynge Priory though was bought by the parishioners of St Alphage, whose own church had become derelict. Any Danish readers of this page will be interested in a Danish link here, as St Alphage was an Anglo-Saxon Archbishop of Canterbury, who was captured by rampaging Danes under King Sweyn, refused to be ransomed, and was killed by the Danes in Greenwich in 1012 (by being pelted with bones and then stuck with an axe, as recorded in the Anglo Saxon Chronical). Alphage, who was an Anglo-Saxon born in Weston Super Mare, had started out as a monk, rising to become the Abbot of Bath, then Bishop of Winchester, where he built and enlarged various churches in the city, and in 1006 he became Archbishop of Canterbury, holding the post for just six years - the first Archbishop of Canterbury recorded as being murdered. In the Danes' favour, it is told that the axe blow may have been a mercy killing by Thorkell the Tall, who had pleaded for Alphage's life with his fellow Danes, and later changed sides to the English; he was also honoured by the later Danish King Cnut, who took his body back from London to be reburied in Canterbury Cathedral. Alphage was canonised in 1078, and is one of just two Anglo-Saxon archbishops kept by the Normans on Canterbury's list of saints.

Before and after (click to enlarge).

Later history of the building:

Anyway, back to our parishioners who took on the Elsynge chapel, their story is of facing continuing repairs, extensively so in 1624-28, and destruction of the rectory and other buildings owned by the Church in the Fire of London, though the Church itself survived, albeit requiring further repairs. It needed further extensive repairs in 1701, with some material apparently taken from the ruins of Elsyng Spital. but even with that, by 1775 the Church became ruinous and unusable, with parishioners complaining of the risk of falling masonry and excessive damp. The Church had to be rebuilt in full, with the new building being opened on the site in 1777, retaining just the 14th Century tower of the previous building. The parishioners, wary of excessive costs after paying out for so many repairs, decided not to employ an architect, and so the new church was designed by the builder William Staines, who was mason to the Royal Exchange. This building was much sneered at: a typical comment being that ‘the decorations plainly show that the designer of the church was totally unacquainted with the five orders of architecture, and he has rendered his ignorance more apparent by a miserable attempt at novelty: invention without genius creates only deformities, and no ornament could have been better adopted by such an architect than skulls without brains’; another that ‘the interior of the Church is probably the plainest, gloomiest and least interesting of all the City churches’.

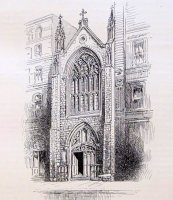

Facade of the 1770s Church to Aldermanbury, and Victorian alteration.

The south wall needed a rebuild in Victorian times, leading to exposure of more worked stones from old Elsynge Hospital, which were again reused. And a decorated façade was added to the London Wall porch side in 1914 (picture below), which included, of interest here, a porch with a number of carved heads: St Alphage and Prior William Elysnge, Edward III (in whose reign the Priory church was built), and George V (King when these carvings were made), and inside, St Mary Virgin and St John Baptist.

Destruction:

The revamp of 1915 was looked on by later commentators as by no means sufficient apology for the earlier work, and the 1770s Church was swept away after World War I damage, with subsequent demolition in the 1920s. The old tower and new porch survived, and the wall monuments were moved there, only to be destroyed in the gutting in World War II. The Victorian font (donated by the Revd Kemp whose monument we saw above), and two ornately carved chairs, had been taken to St Mary Aldermanbury, but that was no escape, as they were also also to be obliterated by bombing. Writing after World War II, a commentater noted that only ‘the portentious Decorated façade [of St Alphage’s 1914 revamp] still just stands, a piece of Ozymandias-work which it is possible nobody ever looked on much’. It too was then thoughtfully demolished.

The 1915 works.

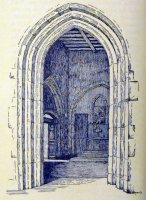

So what we are left with then, is the lower part of the tower, with several pointed arches of the 14th Century, and flint and rubble masonry, as William Elsynge had it built seven centuries ago, with everything that was subsequently added to it, and put inside it, destroyed.

The doomed chairs and font.

Truly we might think the parishioners had committed some offence against the Deity to suffer such issues with their building over so long, with every piece of exterior building and interior decoration they had laboriously constructed at their own expense ground down to dust. But we should remember that these events happened over so many hundreds of years, that in between these several tribulations, generations of churchgoers could attend the Church untroubled.

And more brightly, it was the WWII bombing which better exposed the length of Roman Wall which is the other feature of the site along with the ruins of Elsynge Spital. What we see is an impressive length of wall, with the Roman part being the base (dated 190-225AD), and the upper portions with their lozenge brick decorations and battlements being medieval, dating from 1477 during the War of the Roses, says the information on the site.

The City Wall.