The coastal town of Folkestone, in Kent, is of Roman origin, and while we do not have anything to see from that time, it retains its 14th Century Parish Church (one time church for Folkestone Priory – Benedictine), containing two notable monuments with sculpture, and a late 19th Century restoration saw the addition of fine Salviati mosaics around the altar end, and a painted decorative mural scheme. As one of the Cinque Ports for the defence of the south coast, Folkestone had some military importance, and retains Martello towers on the headlands. It maintained a fishing fleet in the 18th Century, and became a beach resort by mid-Victorian times, so that many imposing villas, guest house and residences were built close to the shore, along with new churches. The apogee of the town was around 1900, when a couple of grand hotels were built west of the old town. Decline and more recent partial renaissance has followed the path of many seaside towns, and today there remains a few picturesque streets in the old town, the Victorian and Edwardian surround, and much modern infill. For the interest of this website, as well as the Parish Church, noted further down this page, there are two significant statues:

William Harvey statue, by Albert Bruce Joy.

William Harvey statue, by Albert Bruce Joy.

new Metropole and Grand Hotels .

new Metropole and Grand Hotels .

These are the two principal statues of Folkestone, augmented in 2011-12 by a couple of modern pieces including a rendering of a ram’s head at the bottom of the Old High Street and a nude female by the shore described as a mermaid. Though the Victorian and Edwardian buildings are grand, with much terra cotta, there is very little even minor sculptural decoration from that period. From the base of the Old High Street by a little harbour, we can look back at a grand residence with eagle sculpture on the pediment (see below), and on the promenade there are a few architectural lions’ heads (see this page for lots of lion head sculpture, and this one for eagle sculpture), but apart from decorative pillars with foliage, I have seen little other sculpture in the town bar the occasional terra cotta head on a building.

A perambulation westwards along the clifftop takes us to views of the two grand hotels, Edwardian extravaganzas of c.1900, which have lots of terra cotta but no sculptural figurework. Close by in the town’s grandstand with decorative ironwork, typical of the breed.

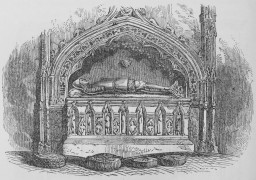

The Parish Church rejoices in the name of St Mary and St Eanswythe, and it is the pride of the church that it retains the remains of the Saxon Saint in a cupboard by the altar (and until 150 years ago, its second pride was that it had a display of a large heap of bones, said to be from some battle; a seemingly not uncommon attraction in South Coast churches at one time). The church itself dates from the 14th Century, and contains an effigy from that time of a knight, perhaps Sir John de Segrave, Baron of Folkestone, d.1343, who rebuilt the Priory. Regardless of whether this is him, it is unusual to find a statue of this age outside the great Cathedrals, and well worth study.

14th Century Knight, and Herdson Monument, 17th Century.

14th Century Knight, and Herdson Monument, 17th Century.

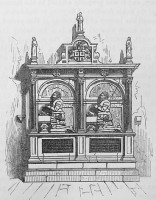

The second monument is the Herdson Monument, of the 17th century, one time lords of Manor of Folkestone. Such kneeler monuments are the norm for the period, and though the most familiar ensemble is of a husband and wife kneeling facing one another across a small prayer desk, such double monuments with two figures facing the same way are not that unusual. The one at the front is John Herdson, d.1722. This is a grand example of the type, with coloured marbles, black shafted columns to Corinthian pillars supporting the entablature above, the two figures in full armour, and with prayer desks covered with tablecloths with gilded fringes. The top of the monument, with a centrepiece containing the shield at arms of the family, bears three female figures. The one at the top is a Virgin and child, the other two are obscure and one has lost her head, the other her hands and part of one arm. Nevertheless, they remain good examples of ideal female sculpture from the period, Classically garbed, rather heavier in body and arm than the ideal of Victorian times, with rounded Hellenic faces, and assured carving of the substantial drapery swathing the body.

Of minor monuments, there were in the 1850s ‘numerous monuments to the Philpots, Reads, Clokes, Jordans, and other of the old resident families’, but these have all gone. What we have left that I have seen are:

While this website does not generally mention floor monuments, we should note a rather splendid Victorian brass to Matthew Woodward, d.1898, vicar for 47 years, restorer of the church and writer of a book on it which shows his interest in the church to be above all in the stained glass windows (which include much work by Kempe). Consciously in medieval style, it depicts a full size brass of the vicar, standing, symmetrically robed, carrying a chalice in his hand, under an arch. Most unusual and a real addition to the church. Almost enough to forgive that it was probably him who got rid of the aforesaid ‘numerous monuments’.

View of Folkestone Church in about 1860.

And the Salviati mosaics – there are ten trefoil-topped panels around the walls of the chancel, and a larger, broader panel behind the altar table. This shows five angels, female and gently Pre-Raphaelite in a Henry Justice Ford sort of way, a little too sweet in the face, but the drapery excellent. Predominantly in blues, greens, reds and gold against a paler background, nicely composed. An inscription at the base reads ‘in loving memory of Frederick Augustus Howe Fitz Gerald’. The other ten panels all contain standing saints, recognisable by their accoutrements – St Peter with his key and so on (not that I personally recognise them all); nine are male, one female. The work of more than one hand, with noticeably more character to some. According to a website called the Salviati architectural mosaic database, the artist was A. Cappello, who did work for Salviati, but had his own London workshop at the time these mosaics were made.The mosaic tesserae - which would still have been made by the Salviati workshops - reflect the light to give a glittery effect, this being through the rough cut to the surface rather than using the older method of setting them at different angles to the surface. The ensemble is completed by much coloured marble or alabaster, painted scenes of the life of Christ on the front of the altar table, probably carved wood under the paint, and four little roundels with a reading angel, winged bull, winged lion, and eagle. And much minor decorative repetitive carving on the borders, pillars etc.

There are good, deep colours to some of the stained glass windows, and we may mention two rather daring small windows showing Adam and Eve and the Serpent, and the Expulsion from Eden. They are in broadly similar style (by Kempe) but the figures seem to have been painted by different artists.

The decorative scheme put in during late Victorian times is poorly preserved in some parts, perfect in others, and includes wall paintings in a pictorial style of the Religious Tract Society, as well as more academic works, the best of which is the Bishops on the Banks of the Severn; also rather nice almost monochromatic angels on the chancel arch and upper walls.

Dying tree on the Faulkner monument (d.1853), and the church Cross.

Dying tree on the Faulkner monument (d.1853), and the church Cross.

Outside, the churchyard has a tolerably sizeable collection of headstones and chest tombs. The most novel is that to Fanny Faulkner, d.1853, if I read the encrusted date correctly, with a panel showing a dying tree in low relief, against what seems to be the gently curved top of a burial chamber. Near to it, an Egyptian obelisk to Henry Anderson, d.1854, and dotted around are some crumbling 18th Century headstones with minor sculptural adornment in the shape of low relief cherub heads and the odd skull. A late 19th Century cross stands on the original base where a medieval cross once stood. We might note that the 19th Century porch retains two of its original three small figures in niches, poorly preserved.

Several churches were put up as the town expanded in the 19th Century. We mention just two, both in Sandgate Road. At the town end, at the western end of one of the main shopping streets, is the tower of Christ Church, the rest of the church having been lost to WW2 bombing. It was put up in 1850-51, the architect being the eminent Sydney Smirke, architect of the Carlton Club in Pall Mall, London, among other works. It had been enlarged in 1869, by the architect J. Gardner, but that is all gone now. The square stone tower retains gargoyle dragons at the top, and fine spirelets.

Christ Church, by Sydney Smirke, and a gargoyle; Holy Trinity tower by Ewan Christian, and statue thereon.

Continuing westward, away from the town centre, past a variety of large Victorian and later properties and various squares leading down towards the sea in classic seaside town fashion, brings us to a rather large church, Holy Trinity, which gives an idea of the prosperity of the town in mid-Victorian times. In an early Gothic idiom, it is by the architect Ewan Christian, erected 1868-9, with the tower, still to his design, going up two decades later. Fellowes-Prynne, an interesting student of G. E. Street, had a hand in the exterior (Porch) and some of the expensive interior decoration, including the font.

Finally, drifting towards the sea and proceeding just a little further brings us to the two grand late Victorian/Edwardian hotels noted earlier: the New Metropole of 1895, and the Grand of 1900. Of prodigious size, most impressive with lots of red brick, glass, and Frenchy curved roofs, but, alas, no sculptural adornment to speak of.

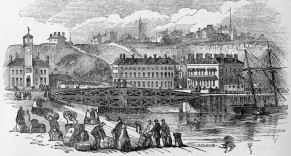

View of Folkestone from the Harbour.

View of Folkestone from the Harbour.

Sculpture in England // Sculpture pages

Visits to this page from 3 Aug 2013: 9,350